Essential Skills

for

Paralegals

Volume II

Authority, Research and Writing

Daniel R. Barber

Published under limited usage authorization by

West Legal Studies

Publishing Company

Copyright © 2004

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

iC

Published under authority of

West Legal Studies

All Rights Reserved

Copyright © 2004

ii

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Table of Contents

ESSENTIAL SKILLS FOR PARALEGAL

VOLUME TWO: AUTHORITY, RESEARCH AND WRITING

Table of Contents .................................................................................. iii

Acknowledgments ................................................................................... vi

Dedication ........................................................................................... viii

Paralegal Rules of Classroom Procedure .................................................... ix

PART ONE: FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH & WRITING ........................ 1

Chapter 1: The Fundamentals of Authority ............................................. 5

§ 1.1 WHAT IS AUTHORITY? ........................................................... 5

§ 1.2 PRIMARY AUTHORITY ............................................................ 5

§ 1.3 USING CITATIONS TO LOCATE AUTHORITY............................... 9

§ 1.4 LOCATING A CASE WITH A CITATION .....................................10

§ 1.5 HOW TO READ A CASE .......................................................... 11

§ 1.6 FINDING STATUTES WITH A CITATION ....................................12

§ 1.7 HOW TO READ A STATUTE .....................................................13

Chapter 2: The Fundamentals of Legal Research ................................. 15

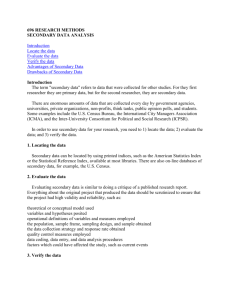

§ 2.1 THE SYSTEM OF LEGAL RESEARCH .......................................... 15

§ 2.2 INDEX RESEARCH .................................................................16

§ 2.3 INDEX SIGNALS ...................................................................17

§ 2.4 USING WORD ASSOCIATION .................................................. 18

§ 2.5 COMMON RESEARCH QUESTIONS ........................................... 20

§ 2.6 VISUALIZING THE BOOKS .....................................................21

§ 2.7 PUBLISHERS ........................................................................22

§ 2.8 LIBRARY SCAVENGER HUNT ASSIGNMENT ............................... 23

§ 2.9 INTERACTIVE STUDY: WORDS AND PHRASES ........................... 24

§ 2.10 INTERACTIVE STUDY: AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE 2D .............27

§ 2.10a AM. JUR. 2D EXERCISE ....................................................... 33

§ 2.11 INTERACTIVE STUDY: CORPUS JURIS SECUNDUM ....................37

§ 2.11a C.J.S. EXERCISE.................................................................40

Chapter 3: The Fundamentals of Legal Writing ..................................... 41

§ 3.1 THE UNIFIED THEORY OF WRITING ........................................ 41

§ 3.2 FORMS OF LEGAL WRITING ...................................................42

§ 3.3 CORRESPONDENCE: DEMAND LETTER .....................................43

§ 3.4 CORRESPONDENCE: CLIENT LETTER ....................................... 47

§ 3.5 10 COMMANDMENTS OF WRITING .......................................... 49

§ 3.6 INTRODUCTION TO ANALYSIS ...............................................50

§ 3.7 COMPARING CASES .............................................................. 50

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

iiiC

§ 3.8 DISTINGUISHING CASES ......................................................52

§ 3.9 EXERCISE IN ANALYSIS ........................................................53

§ 3.10 ANALYZING STATUTES AND RULES.........................................54

§ 3.11 ANALYZING STATUTES EXERCISE ........................................... 57

§ 3.12 HELPFUL HINTS IN LEGAL WRITING ....................................... 58

§ 3.13 MEMORANDUM FORM ........................................................... 59

§ 3.14 EFFICIENCY IN WRITING ......................................................64

§ 3.15 MEMORANDUM ASSIGNMENT ................................................. 65

§ 3.16 EXAMPLE OF AN INTEROFFICE MEMORANDUM ......................... 67

PART TWO: RESEARCH & WRITING IN LITIGATION ............................ 73

Chapter 4: Citing Authority .................................................................. 75

§ 4.1 MANDATORY AND PERSUASIVE AUTHORITY.............................. 75

§ 4.2 AUTHORITY EXERCISE ........................................................... 77

§ 4.3 AUTHORITY DISCUSSION POINTS ...........................................77

§ 4.4 AUTHORITY EXERCISE ........................................................... 78

§ 4.5 REAL WORLD CITATIONS........................................................80

§ 4.6 PINPOINT CITATIONS ............................................................84

§ 4.7 PINPOINT EXERCISE ..............................................................85

§ 4.8 STAR PAGINATION .................................................................86

§ 4.9 AUTHORITY AND CITATIONS ................................................... 87

§ 4.10 AUTHORITY AND CITATIONS EXERCISE ..................................87

Chapter 5: Law Library Litigation Support ............................................ 89

§ 5.1 THE PARADOX OF LITIGATION ................................................ 89

§ 5.2 DEFINITIONS ........................................................................90

§ 5.3 FORM BOOKS ........................................................................90

§ 5.4 ASSIGNMENT: LOCATING FORM BOOKS .................................... 91

§ 5.5 EXAMPLE OF A FORM BOOK ....................................................93

§ 5.6 INTERACTIVE STUDY: AM.JUR. PROOF OF FACTS ....................... 94

Chapter 6: Litigation Documents .......................................................... 99

§ 6.1 THE SUMMONS .....................................................................99

§ 6.2 SUMMONS EXAMPLE ............................................................ 101

§ 6.2 THE COMPLAINT ................................................................. 102

§ 6.3 CAUSES OF ACTION ............................................................ 106

§ 6.4 CAUSES OF ACTION EXERCISE ............................................. 107

§ 6.5 ESTABLISHING CAUSES OF ACTION ...................................... 108

§ 6.6 THE CLAIMS ....................................................................... 110

§ 6.7 EXAMPLE OF A COMPLAINT .................................................. 112

§ 6.8 THE ANSWER ..................................................................... 116

§ 6.9 EXAMPLE OF AN ANSWER .................................................... 118

iv

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

6.10 INTRODUCTION TO DISCOVERY ......................................... 120

6.11 THE INTEGRITY OF THE PROCESS ....................................... 121

6.12 INTERROGATORIES ........................................................... 122

6.13 ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES ....................................... 124

6.14 INTERROGATORY TECHNIQUES .......................................... 126

6.15 INTERROGATORY EXAMPLE ................................................ 128

6.16 REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS ............................................... 131

6.17 RESPONDING TO REQUESTS ............................................... 132

6.18 REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS TECHNIQUES............................. 135

6.19 REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS EXAMPLE ................................. 137

6.20 REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION .............................................. 139

6.21 DISCOVERABLE MATERIALS ................................................. 139

6.22 NON-DISCOVERABLE MATERIALS ......................................... 139

6.23 RESPONDING TO PRODUCTION ........................................... 141

6.24 DEPOSITIONS ................................................................... 146

6.25 PREPARING FOR THE DEPOSITION ....................................... 146

6.26 DEPOSITION FOLLOW-UP ................................................... 149

6.27 DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT .................................................. 153

6.28 EXAMPLE OF DEPOSITION DIGEST ....................................... 157

PART THREE: TRADITIONAL RESEARCH & WRITING ......................... 159

Chapter 7: Authority- Law Books ....................................................... 161

§ 7.1 THE FUNCTIONS OF LAW BOOKS .......................................... 161

§ 7.2 LAW BOOKS: SECONDARY & NON-AUTHORITY ....................... 162

§ 7.3 LAW BOOKS: PRIMARY AUTHORITY ....................................... 174

Chapter 8: Traditional Research Tools ............................................... 181

§ 8.1 WHERE SHOULD YOU BEGIN? ............................................... 181

§ 8.2 EXPANDING YOUR RESEARCH ............................................... 181

§ 8.3 LEGAL RESEARCH FLOW CHART ............................................ 182

§ 8.4 INTERACTIVE STUDY: SCAVENGER HUNT ............................... 183

§ 8.5 INTERACTIVE STUDY: AMERICAN LAW REPORTS ..................... 184

§ 8.6 WEST DIGESTS ................................................................... 196

§ 8.7 AN INTRODUCTION TO SHEPARD’S ........................................ 203

§ 8.8 SHEPARD’S CITATORS .......................................................... 207

§ 8.9 SHEPARD’S REVIEW ............................................................. 216

§ 8.10 FEDERAL CASE LAW RESEARCH ........................................... 218

§ 8.11 U.S. SUPREME COURT CASES .............................................. 218

§ 8.12 U.S. APPELLATE COURT CASES ............................................ 221

§ 8.13 U.S. DISTRICT COURT CASES .............................................. 222

§ 8.14 FEDERAL STATUTORY RESEARCH ......................................... 223

§ 8.15 STATE STATUTORY RESEARCH ............................................. 225

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

vC

Chapter 9: Notices, Motions and Briefs............................................... 227

§ 9.1 WHAT ARE MOTIONS? .......................................................... 227

§ 9.2 WHAT ARE NOTICES? ........................................................... 229

§ 9.3 WHAT ARE BRIEFS? ............................................................. 229

§ 9.4 EXAMPLE: COMBINED MOTION, NOTICE, & BRIEF ................... 230

§ 9.5 EXAMPLE OF SEPARATE MOTION .......................................... 231

§ 9.6 EXAMPLE OF SEPARATE NOTICE ........................................... 232

§ 9.7 EXAMPLE OF SEPARATE TRIAL BRIEF .................................... 233

§ 9.8 RESEARCH & WRITING ASSIGNMENT .................................... 238

§ 9.9 EXAMPLE OF A TRIAL BRIEF .................................................. 239

§ 9.10 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................................... 243

PART FOUR: NON-TRADITIONAL RESEARCH & WRITING .................. 245

Chapter 10: Accessing Authority Online .............................................. 247

§ 10.1 ONLINE SITES ................................................................... 247

§ 10.2 QUERY FORMULATION FOR ONLINE RESEARCH ..................... 248

§ 10.3

LexisNexis: SIGNING ON ................................................. 250

§ 10.4

LexisNexis: BEGINNING YOUR SEARCH ............................. 251

§ 10.5

LexisNexis: ENTERING YOUR SEARCH QUERY .................... 252

§ 10.6 LexisNexis: SEARCH RESULTS PAGE .................................. 253

§ 10.7

LexisNexis: QUERY RESULTS PAGE VALIDATION ................ 254

§ 10.8

LexisNexis: OPENING A CASE IN RESULTS PAGE ................ 255

§ 10.9 LexisNexis: SHEPARDIZING A CASE .................................. 256

§ 10.10 LexisNexis: TABS- RESEARCH TASKS ................................. 257

§ 10.11 LexisNexis: TABS- SEARCH ADVISOR................................. 258

§ 10.12 LexisNexis: TABS- GET A DOCUMENT ................................ 259

§ 10.13 LexisNexis: TABS- SHEPARD’S .......................................... 260

§ 10.14 LexisNexis: SECONDARY SOURCES ................................... 261

§ 10.15 WESTLAW: SIGNING ON .................................................. 262

§ 10.16 WESTLAW: SEARCHING .................................................. 263

§ 10.17 WESTLAW: ENTERING YOUR QUERY ................................ 264

§ 10.18 WESTLAW: SEARCH RESULTS .......................................... 265

§ 10.19 WESTLAW: VALIDATION RESEARCH .................................. 266

§ 10.20 WESTLAW: VALIDATION RESULTS ..................................... 267

§ 10.21 ELECTRONIC V. LAW LIBRARY RESEARCH .......................... 268

vi

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Chapter 11: The Desperate Researcher ............................................ 269

§ 11.1 “I CAN’T FIND ANYTHING!” ................................................ 269

§ 11.2 COMMON RESEARCH ROADBLOCKS ..................................... 270

§ 11.3 ADVANCED TECHNIQUES IN TRADITIONAL SOURCES ............ 273

§ 11.4 REVIEW: AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE ................................. 273

§ 11.5 REVIEW: CORPUS JURIS SECUNDUM ................................... 274

§ 11.6 REVIEW: WEST DIGESTS ................................................... 274

§ 11.7 REVIEW: AMERICAN LAW REPORTS .................................... 275

§ 11.8 THE GENERAL DIGEST ....................................................... 278

§ 11.9 RESTATEMENTS OF THE LAW .............................................. 280

§ 11.10 EXAMPLE OF RESTATEMENTS OF LAW ................................ 283

§ 11.11 RESTATEMENTS EXERCISE ................................................ 284

§ 11.12 LEGAL PERIODICALS ....................................................... 285

Chapter 12: Non-traditional Writing Techniques ................................. 287

§ 12.1 SYNTHESIZING AUTHORITY ................................................ 287

§ 12.2 SYNTHESIZING PRIMARY AND SECONDARY ......................... 287

§ 12.3 EXAMPLE USING PRIMARY AND SECONDARY ......................... 289

§ 12.4 SYNTHESIZING STATUTES AND CASES................................. 290

§ 12.5 EXAMPLE USING A STATUTE AND A CASE............................. 290

§ 12.6 CITING DISSENTING AUTHORITY ....................................... 291

§ 12.7 EXAMPLE OF CITING A DISSENT ......................................... 292

Appendix A: The Client ...................................................................... 293

Appendix B: Interoffice Memorandum Authorities .............................. 301

Appendix C: Legal Analysis Exercise Case Example ............................. 331

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

viiC

Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without the

hard work of Alyssa Navallo. Her tireless efforts have

made this manual more functional. Her insight has

lifted the learning experience provided within these

pages to a very high level. Her partnership has made

the process of designing educational opportunities

even more rewarding. She is, quite simply, amazing.

Dedication

This manual is lovingly dedicated to my Mother, who

valued and appreciated education as much as anyone

I have known. Born in 1923, she finished high school

but was unable to attend college. She supported my

Father as he attended seminary, and with him raised

five children. Without complaint, she went back to

work at a time most were thinking of retirement to

help support all her children as they attended

universities, and saw four of them graduate.

During holiday gatherings, our family would play

games that required a knowledge of history, science,

current events, and other intellectual prowess. And

yet this woman who never attended a day of college

never lost a game to her “educated” children, or anyone

else, until late in her life. (Her lawyer son finally

beat her in her early seventies, and I am convinced

he counts this as a higher achievement than passing

the bar.) She taught me that education is more than

letters on the pages of books. Education is that which

is remembered after what was once studied has been

forgotten. She was the most educated person I have

ever known.

I hope she knew what an inspiration she was, and

still is, to her children.

D.R.B.

viii

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

P.R.C.P.

THE PARALEGAL RULES OF CLASSROOM PROCEDURE

(a)

(b)

(a)

(b)

Rule 1.

Scope of Rules

These rules exist for the purpose of establishing appropriate

paralegal skills and instilling proper professional behavior in

students entering the paralegal profession. When filing documents

in court, attending a court hearing or working for an employer,

certain standards will be expected of the paralegal, including

timeliness and quality work product. To that end, students will

be expected to meet similar standards and expectations during

their educational experience. In addition, these rules are

established to make clear the requirements that must be achieved

in order for a student to obtain his or her paralegal certificate.

These rules may be superceded, added to, or modified by the

school or instructor offering or teaching your paralegal program.

Rule 2.

Attendance

Students are required to attend each class in it’s entirety.

Unexcused absences may not exceed a maximum set by the school

offering this program.

Just as a judge will not tolerate an attorney being late to court,

tardiness in this class will be discouraged. Any student not counted

present at the beginning of class will be considered absent for the

entire class, unless:

(1) the student provides written excuse from

a licensed physician, or

(2) the student provides written excuse from

her or his employer, or

(3) arrangements have been made with the

school or instructor to accommodate such

considerations as work schedules, or

(4) the instructor in his discretion approves

the absence or tardiness, in the interest of

justice.

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

ixC

(c)

Instructors may or may not be present during assigned

law library research sessions. Students should not rely

on instructors or library staff during such sessions.

Rule 3

Written Assignments

(a) All assignments are to be turned in on their due date.

Each class day an assignment is late will cost the student the

equivalent of one full letter grade unless:

(1) a Motion for Enlargement of Time has been turned

in and granted

(2) the instructor has approved the delay

(b)

Each assignment must receive a passing grade for the

student to receive his or her certificate.

(c)

Each assignment shall be prepared in the following

manner:

(1) Assignments shall be typed or printed. No

handwritten assignments shall be accepted

(2) All assignments shall be prepared on 8 ½

by 11 inch white bond paper

(3) All assignments shall be double spaced

unless otherwise instructed

(4) Assignments shall be typed on only one side

of each sheet of paper

(5) Each written assignment shall be stapled

on top left hand corner

(6) The student’s name shall be typed or written

on top right hand corner of the front page

(7) No folders, file holders, or plastic bindings

shall be accepted

(d)

Violation of these rules shall result in the loss of up to

one letter grade for each violation, at the instructor’s discretion.

Rule 4.

Examinations

(a)

Unless the school or instructor states otherwise, students

are required to pass each examination.

(b) Make up examinations may be offered, at the discretion

of the instructor, in the interest of justice.

x

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

V O L U M E II

part 1

Fundamentals of Research & Writing

the keys to the kingdom

Part 1 Chapters:

1. Authority: Fundamentals

2. Research: Fundamentals

3. Writing: Fundamentals

Legal analysis is the application of the law to a given

set of facts. This analysis is most often found in

legal writings, by both the parties and by the court

itself. To find the applicable law to the given set of

facts, we engage in legal research. When researching,

the goal is first and foremost to find all relevant

authority. Authority is anything the court can, or

must, use in reaching its decision. The truly good

researcher is not a crusader for the client in the library,

but instead searches for applicable law to the client’s

Assignments

situation, good or bad.

While an internal, or interoffice, memorandum applies

the law in an objective manner, an external

memorandum or brief applies any authority cited to

the advantage of the client, minimizing the damaging

points of damaging authority, and maximizing the

favorable points of favorable authority. The goal of

this chapter is to introduce the student to the concept

of legal analysis, proper analytical form, and to use

these skills when preparing an interoffice

memorandum. In addition, the student will begin

developing skills related to legal research. These

skills will include: proper utilization of indexes,

research within legal encyclopedias, and how to find

cases and statutes in a law library.

As the student takes these first steps in legal writing

and legal research, it will be helpful to know that

there are some basic concepts and systems that

should be followed, and that, in fact, make your job

easier. First, accept the fact that what you think

doesn’t matter at all! The only thing that matters in

legal writing and legal research is “what the law is.”

In addition, when creating a legal document, don’t

use your own, individual style of writing. You must

use the analytical system that you will be taught. In

fact, it makes writing easier because all you have to

do is follow each step of the system. By following

Law Library: Case Law

§ 1.4

Due Date:

/

/

Law Library: Statutes

§ 1.6

Due Date:

/

/

Law Library: Scavenger

Hunt

§ 2.8

Due Date:

/

/

Law Library: Words &

Phrases

§ 2.9

Due Date:

/

/

Law Library: Am. Jur. 2d

§ 2.10

Due Date:

/

/

Law Library: C.J.S.

§ 2.11

Due Date:

/

/

Interoffice Memo

§ 3.15

Due Date:

/

/

Other Assignment:

§ ___.___

Due Date:

/

/

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

1C

these guidelines, and accept them, the result will be a

document that relies upon authority instead of personal

opinion, and a document that anticipates, or argues,

what the ultimate result of the court will be, based

upon that authority.

Open your mind. When talking about the law, the rules

of writing and research are different.

Legal Junk Food

Q. Doctor, before you

performed the autopsy, did

you check for a pulse?

A. No.

Q. Did you check for blood

pressure?

A. No.

Q. Did you check for

breathing?

A. No.

Q. So, then it is possible that

the patient was alive when

you began the

autopsy?

A. No.

Q. How can you be so sure,

Doctor?

A. Because his brain was

sitting on my desk in a jar.

Q. But could the patient have

still been alive, nevertheless?

A. Yes, it is possible that he

could have been alive and

practising law

somewhere.

2

authority

The court, in making its decision, relies on

cases, statutes, regulations, even articles and

commentary by private individuals. Whatever

it is that the court is relying on, it is called

authority. As we will see, there are different

kinds of authority: primary, secondary, mandatory, persuasive, and non-authority. In this

chapter, we will concentrate on identifying primary, secondary, and non-authority. Understanding these stepping stones of authority will

make the remainder of this Segment more productive. We will discuss more advanced applications of authority, including identifying mandatory and persuasive authority, in a later chapter.

citations

In order to eventually refer to an authority, one

must be able to provide a legal “address.” In

this chapter, we will provide the foundations

for case law and statutory citation form, using

the Uniform System of Citation, often referred

to as “Bluebook” form.

analysis

Legal analysis is the application of any form of

law to a specific set of facts. There is a very

quantifiable system of analysis. The beauty of

the system is that, once understood, the job of

the author is actually made easier, and the resulting analysis more powerful and convincing.

The system is referred to as IRAC, and every

lawyer learns it in law school.

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

These three skills eventually work together: in

any analysis, the paralegal provides citations to

the authority being cited.

PART 1 OBJECTIVES

Primary and Secondary Authority

Students should be able to identify the differences

between primary and secondary authority, and what

distinguishes official from unofficial authority.

Correspondence

Learn to create a demand letter and basic client

correspondence.

Legal Analysis

It is critical that a paralegal understand the process

and structure of legal analysis.

Legal Memorandum Form

Paralegals need to communicate with the attorney

using memorandum form, often incorporating

analytical skills.

Index Research

The foundation of all legal research is the ability to

use indexes. From the concept of “cartwheeling”

to the basic “hierarchical structure” of legal indexes,

paralegals need to efficiently utilize these

fundamental research tools.

Breaking Rules Into Elements

Students will be taught how to break a rule of law,

the hearsay rule, into elements in order to properly

apply them to factual situations.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

3C

4

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

chapter 1

The Fundamentals of Authority

§

1.1 WHAT IS AUTHORITY?

Authority is anything the court can or must use in

reaching its decision.

To be a competent researcher, knowing how to find

cases, statutes, and other legal materials is not

enough. The lawyer or paralegal must also anticipate

whether the court will be persuaded by the material.

To determine this, the researcher must initially be

able to identify two things:

Is the authority law or non-law?

(primary or secondary)

If it is law, what weight will it carry?

(mandatory or persuasive)

_______________________________________

Primary/Secondary

Understanding the difference between primary and

secondary authority is fairly simple. If the authority

is law, it is primary. If the authority is not law, it is

secondary.

Primary Authority

Any form of law is considered primary authority.

Example: A statute, case, constitution,

or any other form of law.

Secondary Authority

Secondary authority is non-law.

Example: A comment from a legal

encyclopedia.

_______________________________________

Mandatory/Persuasive

Determining what weight the authority carries is

equally important. If the material is from a higher

authority than the court in which your client’s case is

being heard, and within the court’s jurisdiction, it is

mandatory. In other words, the court must follow the

material the researcher has located unless it is

established that the law has been superceded or has

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

5C

A rule protective of law-abiding citizens is not apt to flourish where its

advocates are usually criminals.

William O. Douglas

been declared unconstitutional. If the material is from

the same level court or lower, that material is persuasive,

and the court can choose whether to follow the authority

or not.

Mandatory Authority

The researcher is always looking for mandatory

authority. In theory, the court must follow such

authority.

Example: A case you found in the law library

that came from a higher court in the

appropriate jurisdiction.

Persuasive Authority

While the researcher always looks for mandatory

authority, it is usually persuasive authority that is

found, which the court is not required to follow.

Example: A case from the same level of court,

or a case from a different jurisdiction.

Stare Decisis and Persuasive Authority

Stare Decisis is a doctrine that holds that a court’s

previous decision should be followed unless there

is a compelling reason not to do so. Although a

court is not required to follow a previous ruling

by the same level court, it will do so unless a

compelling reason has been provided.

_______________________________________

Non-authority

If authority is anything the court can or must use in

reaching it’s decision, then non-authority is anything

the court would never use in reaching its decision,

such as a case that had been overturned.

Example: A case that has been reversed by a

higher court. A statute that has been

superceded. A research book that is used as

an index, or that could never be quoted.

In this chapter we will discuss the identification of primary,

secondary, and non-authority.

6

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

1.2 PRIMARY AUTHORITY

There are many kinds of laws. Each serves its own purpose.

Some can supercede others. Following is an introduction to

the 10 kinds of law in the rough order of supremacy.

Constitution

The highest form of law. The fundamental law that

establishes the basic rights and obligations of citizens,

and creates the branches of government. The U.S.

Constitution is the highest law in the country. In

addition, states have their own individual constitutions.

Statutes

Laws created by the legislative branch of government.

For instance, the U.S. Congress creates federal statutes

contained in the United States Code (U.S.C.). State

legislatures create statutes for their own states. Statutes

are enacted law.

Opinions

An opinion is a decision of the court applying law to

specific factual situations. An opinion is often referred

to as a case or case law. For example, the case of Roe

v. Wade is an opinion of the court that applied what the

court deemed was a Constitutional right for a woman to

obtain an abortion. Opinions are common law.

Treaties

An agreement between two or more governments. The

President signs treaties, with the consent of the Senate.

For example, the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT)

was negotiated by the United States and the Soviet

Union, but needed to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate

before it could become law.

Executive Orders

A law created by the highest entity of the executive

branch, such as the President or Governor. An example

of an executive order is a pardon of someone convicted

of a crime.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

7C

A lawyer should never ask a witness on cross-examination a question unless in

the first place he knew what the answer would be, or in the second place he

didn’t care.

David Graham

Administrative Rules

Rules and regulations created by state and

federal administrative agencies. For instance,

the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

creates rules governing air traffic throughout

the country.

Administrative Decisions

Decisions by administrative agencies applying

administrative rules to factual situations. For

example, the FAA can fine a person for making

a joke about a bomb in an airport. After a

hearing, the agency would issue a report

detailing its decision.

Rules of Court

Rules that govern the procedures of state and

federal trial process. Court rules are created

by the legislature, and/or the highest court in

the state. For instance, the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure are the court rules for civil federal

trials.

Charters

The local equivalent of a constitution. The basic

and fundamental law of a local government.

Establishes the structure of the local

government in that jurisdiction.

Which of the following are

primary authority?

_______ a case

Ordinances

_______ a statute

The local equivalent of a statute. Rules that

_______ an ordinance

_______ an index

members of the community are expected to

_______ a dictionary

follow. If a person fails to cut his or her lawn,

_______ the SALT Treaty

he or she is most likely violating an ordinance.

_______ Colo. Rev. Stat. §131.110

_______ an encyclopedia

_______ a Presidential Pardon

The researcher’s first goal is to locate primary

_______ an administrative rule

authority. The researcher may utilize secondary or

_______ a city charter

_______ Roe v. Wade

non-authority to get there, but law is almost always

_______ U.S. Constitution

the focus of research.

_______ Kansas Constitution

_______ a court opinion

_______ an executive order

8

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§ 1.3

USING CITATIONS TO

LOCATE AUTHORITY

In order to utilize authority, a researcher or author of a

legal document must be able to locate and refer to

that authority. This is done through citations. A

citation is a legal address. In the following pages,

students will be asked to locate various citations in a

law library. In later chapters, students will be taught

the form of a legal memorandum, and will learn the

system of basic legal analysis. Thus, authority, research, and writing are ultimately linked.

authority

Before a researcher steps foot in a law library, he or

she must understand what the books contain, and

what the basic function of those law books are. For

instance, secondary authority (non-law) is used mainly

to locate and explain primary authority (law).

research

Encyclopedias are an excellent example of secondary

authority. The purpose of a legal encyclopedia is to

provide a basic explanation of most areas of the law,

In addition, encyclopedias, as with most forms of

secondary authority, provide citations that lead the

researcher to the actual law (such as cases or statutes). It is the law that is usually quoted or relied

upon in making a legal argument.

writing

Once the researcher has identified various authorities

that are relevant to the legal matter in question, he

or she should refer to those authorities in a legal

writing, such as a brief or motion. As we will see Legal Junk Food

later, briefs are documents that attempt to persuade

the court to rule in favor of one side or the other. The COUNSEL

The respiratory arrest means

court doesn’t care what the attorney or paralegal no breathing, doesn’t it?

thinks. It is obviously more likely to pay attention to WITNESS

a statute, or a court opinion. This is why we want to That’s right.

COUNSEL

rely on primary authority in legal writing.

And in every case where there

is a death, isn’t there no

breathing?

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

9C

§ 1.4

LOCATING A CASE WITH A CITATION

Case law means court opinions. Court opinions are considered

common law, which means they arise from a factual dispute

the outcome of which has been determined by a judge. But

how does a paralegal locate case law? It depends on the

information the paralegal has when beginning research.

If the paralegal is provided with a citation . . .

A citation is a legal address. Almost any legal writing may be

cited, including, of course, cases. Following is a typical citation:

Canino v. New York News, 475 A.2d 528 (N.J. 1984)

Assignment 1.4 a

Title

Canino v. New York News is the name of the case. The

title is always either italicized or underlined.

Locate the following cases

in the law library. You do not

have to copy the case.

Instead, write down the first

sentence the case after the

caption.

Volume

475 is the volume number.

Martinez v. State, 961 P.2d 752 (Nev.

1998)

Ward v. State, 1 S.W.3d 1 (Ark. 1999)

Publication

A.2d stands for Atlantic Reporter, second series.

Reporters (and Reports) are collections of opinions. In

this case, we have a regional reporter, collecting opinions

from appellate level courts within the Atlantic Region.

Page

528 is the page number.

U.S. v. Barrow, 118 F.3d 482

(6th Cir. 1997)

Court

N.J. stands for the Supreme Court of New Jersey,

the court that authored the opinion.

Arizona v. Roberson,

486 U.S. 675 (1988)

Year

1984 is the year the opinion was decided.

To find the case all one needs is the publication, volume and

page. Find the publication (Atlantic Reporter, 2d series), the

volume (475), then the page (528).

If the paralegal has been provided with a research issue . . .

There are many publications that help the researcher locate

cases, statutes, and other forms of authority. Examples include

legal encyclopedias, digests, annotations, and form books.

10

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

1.5 HOW TO READ A CASE

Official reports are published by the government (either

state or federal) and generally include only the official

opinion of the court. Unofficial reporters are published by

private publishers, such as West Publishing. They contain

the exact same opinion, word for word. The unofficial

reporters also provide tools to assist the researcher.

Reporters contain the following:

Syllabus

This is a short synopsis of the case. It provides the

researcher with a snapshot of the legal matter in

question and the result of the case being read.

Headnotes

A headnote is a summary of a specific portion of the

case. Each headnote is numbered (1, 2, 3, etc.) and

each headnote number refers to a point within the

opinion. (Unfortunately, if there is only a single

headnote for a case, it is left unnumbered. For

research purposes, it should still be considered

headnote number 1.) Thus, if the researcher was

only interested in headnote number 5, she or he

could simply look for a bracketed number [5] within

the opinion. This allows the researcher to quickly

identify the points in an opinion most relevant to

the issue at hand. Please note, however, that before

a researcher relies on any case, the entire opinion

should be read.

Key Numbers

Reporters are generally published by WestGroup (now

owned by Thomson Publishing), and therefore utilize

West’s Key Number System. This is a mechanism for

broadening the scope of research, and will be covered

at a later point in this manual. The Key Number

references are provided at the beginning of each

headnote, represented by a key symbol, a topic, and

a number.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

11C

Line of Demarcation

This line, at the end of the last headnote, indicates that all

that follows is the official, word for word opinion of the

court. Everything above is provided by the publisher, and

may not be quoted. Everything below is the court opinion,

and may be quoted. (Again unfortunately, if the last headnote

ends at the bottom of a page, the publisher does not provide

a line of demarcation. One simply has to realize that the

top of the next column is the beginning of the opinion.)

The Opinion

The opinion is the decision of the court and follows the line

of demarcation. Even though it is not captioned as such,

the opinion that is provided after the line of demarcation is

the majority opinion of the court. If there is a dissenting or

concurring opinion, those will be titled as such and provided

after the majority. It is almost always the majority opinion

that the researcher is interested in, since it has the force of

law.

Almost every opinion has three elements, and it is up to

the researcher to identify those elements as the case is

being read.

1. History

The court will usually begin by providing a quick overview

of how the case got to that point. This is important to

know, but the history is not usually quoted.

2. Reasoning

This is what the researcher is going to quote in a

memorandum or other legal document. It is the logic

the court uses to reach its result. This is what will

convince, or deter, a judge to follow your legal argument.

3. Disposition

The result of the court’s decision. The most common

dispositions are for the court to affirm, reverse, modify,

or remand. Remember, if the disposition of the case

you are reading reverses, it does not mean the case

you are looking at is reversed. It is the earlier, lower

court case that has been reversed by this later opinion.

12

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Diagram 1a: Example of a Case

Caption

Headnote

Syllabus

Brief explanation of

the case.

The

result

of

the

opinion

(here,

“Petition denied”)

does not refer to the

validity of this

case. It refers to

the validity of the

case from which the

appeal came.

Headnote

Headnote

Headnote

Line of

Demarcation

Key

Everything below the

line is the opinion of

the court, and may be

quoted. The material

above is provided by

the publisher, and

therefore should not

be quoted.

Headnote

Reference

Point

Headnote

Opinion

Headnote

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

13C

§ 1.6

FINDING STATUTES WITH A CITATION

A statute is a law created by the legislature. Statutes are not

about specific factual situations, as are cases. Instead, statutes

act as the general rules for society.

There are federal statutes and state statutes. The researcher

may locate statutes in a couple of different ways, depending

on the information provided.

If the paralegal is provided with a citation . . .

A citation is a legal address. As mentioned previously, almost

any legal writing may be cited, and that includes, of course,

statutes. Following is a typical federal statutory citation:

Assignment 1.6 a

Locate the following

statutes in the law library.

You do not have to copy

the statute. Write down

the first sentence of each

statute.

42 U.S.C. §1204

Iowa Code Annotated

§85.27

Nev. Rev. Stat. §37.010

42 U.S.C. §1204 (1984)

Title or Chapter

42 stands for Title 42. In many state statutes, the 42

might stand for Chapter. In either case, this is the

number to which the researcher would be first led.

Publication

U.S.C. stands for the United States Code.

Section Symbol

§ stands for “Section.” §§ stands for “Sections.” For

example: 42 U.S.C. §1204, or 42 U.S.C. §§1204 to

1207. It would also be appropriate to write 42 U.S.C.

Sec. 1204.

Year

1984 is the year the statute was enacted. (Not all

jurisdictions require the year in statutory citations.)

To find the statute, all one needs is the publication, title (or

chapter), and section. Find the publication (United States

Code), the title (42), then the section number(1204).

If the paralegal has been provided with a research issue . . .

There are many publications that help the researcher locate

cases, statutes, and other forms of authority. Examples include

legal encyclopedias, digests, annotations, and form books. But

if the researcher is specifically looking for statutory authority,

start in the index to the statutes being researched.

14

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

1.7 HOW TO READ A STATUTE

Official statutes are published by the government

(either state or federal) and generally include

only the statutes themselves.

Unofficial statutes are published by private

publishers, such as West Publishing. They contain

the exact same statutes, but also contain

additional research tools and resources.

For example, the Interpretive Notes and Decisions

below provide references to cases that have

actually interpreted and applied the statute in

question.

Diagram 1b: Example of a Case

The Statute

Usually

surprisingly

short, the

statute is the

only part that

should be

quoted.

Research

tools

This part is not

law. These are

other sources

that have been

provided to you

to expand your

research.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

15C

16

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

chapter 2

The Fundamentals of Legal Research

§

2.1 THE SYSTEM OF LEGAL RESEARCH

Following are examples of common legal reference

materials found in almost every law library:

Annotations

Legal treatises

Form books

Legal encyclopedias

Legal dictionaries

Litigation aids

Digests

Legal Periodicals

These are just a fraction of the research materials

available in a law library. They serve, sometimes subtly,

different purposes.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Some

Some

Some

Some

Some

Some

Some

Some

Some

comment extensively on areas of law.

try to educate.

assist in strategies.

assist in research.

cover almost all areas of law.

cover only a single topic.

contain selected primary authority.

contain only secondary authority.

contain only non-authority.

All of the above have one thing in common: the system

by which information within them are accessed. For

our purposes, we will call this system the Unified Theory

of Research. The good news is that it is really very

simple. Almost basic. That is the goal of the system.

Because having all the information at your fingertips,

even at the expense of millions of dollars in legal

materials, is pointless if the information is difficult or

impossible to locate. So, what is the system?

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

17C

Index to Main Volume to Additional Authority

In almost all research materials, the researcher

should begin in the index, which will lead to the

main volumes within that same set of books, which,

in turn, will lead to additional authority, such as a

case or statute.

Your initial reaction may be, “What’s the big deal?”

That’s the point. Don’t fight it. Don’t make research

harder than it has to be.

In fact, there are only two sets of widely used

materials that don’t follow this unified theory. So

the sooner you accept this system, the sooner you

will become an excellent researcher!

§

2.2 INDEX RESEARCH:

THE HIERARCHICAL SYSTEM

The general rule is that, in whichever set of books

the researcher is in, start in the broadest index.

Sometimes it’s called the General Index, sometimes

the Descriptive Word Index. When researching,

always start in the index.

In fact, there are only a couple of books in the entire

library that do not follow the rule to start in the

index. Reports and reporters, as we will see, contain

opinions of the court. Since opinions come out day

by day, year by year, they are chronological. There is

no index. (Although, as we will see, Digests act as

an index to case law.)

It is helpful to understand that indexes use a

“hierarchical” system. This means that the index

starts with a topic, then a subtopic, then a subsubtopic, and so forth. In this system, the subsubtopic relates to the subtopic, which in turn relates

to the topic. For an example, study Exhibit 2a.

18

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

2.3 INDEX SIGNALS

Beginning researchers are often confused by signals. Signals

are actually just research assistants, attempting to guide

the researcher to the appropriate point within the index.

They act just like sign posts.

The most common signals are:

infra or ante

Look for your topic below within the same heading.

supra

Look for your topic above, within the same heading.

this index

Look for the referenced topic as a general, broad topic

within the same index series.

Diagram 2a: Example of an Index

Topic

subtopic

sub-subtopic

sub-sub-subtopic

The last entry under this

example would therefore

read:

Witn § 389 deals with the

validity of a privilege as to coconspirators that involve a

husband and wife under the

topic of Privileges and

Communications

Privileges and Communications, con’t

Habeas Corpus Const L § 327

Wills and Estates Estates § 84

Husband and Wife Witn § 359

Co-conspirators

Accomplice Witn § 524

Validity of privilege as to Witn § 389

Spouse as victim Witn § 296

Waiver Witn § 274

Wills See Habeas Corpus, supra

Institutions

Medical Staff Phys & S § 165

Relatives, communication

with children Hosp § 48

Spouse See Marriage, this index

International Law Int L § 294

The topic & section abbreviations in an index, such

as Witn § 389, always lead the researcher to the

main volumes of the publication being researched.

Each index has an Abbreviation Table as well.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

19C

§

2.4 USING WORD ASSOCIATION

When conducting legal research, one should generally begin

in the index. Unfortunately, the researcher is at the mercy

of the quality of the index, since some indexes are better

than others. One means of locating possible places in an

index where a topic might be covered is word association,

sometimes called cartwheeling.

When beginning research in Court Rules, first write out (or

concentrate on) the question to be researched. Look for

any key words or terms. Read the following question:

According to court rules, must the Summons inform

the defendant of the time he has to file an Answer?

Our key terms would be:

Summons

Time

Answer

One problem, however, is that the person who created the

index might refer to one of our terms under a different

topic. For instance, while we may call the pleading which

initiates a suit complaint, some states might call it a Motion

for Judgment or Petition. It may be helpful to write down

the alternatives.

Summons

Citation

On-Point

When researching, the

object is to find

relevant material to the

issue

being

researched. This is

often referred to as

locating “on-point”

authority, or authority

that is “on all-fours.”

20

Time

Response

Answer

Defense

In addition, look for alternate areas under which key terms

might also be dealt with. For instance, while many indexes

would refer to “discovery” under that term, some deal with

it under the broad heading of “pre-trial procedures.” The

researcher would then have to look for “discovery” as a

topic under “pretrial procedures.” Our alternate terms further

alter our list.

Summons

Citation

Return of

Service

Time

Response

Deadline

Answer

Defense

Pleading

Now,

when weVolume

research

Essential Skills for

Paralegals:

II in the index, we have dramatically

increased the chances of finding “on-point” material.

Exercise 2.4(a)

Assume you are researching the following topics.

Cartwheel them to better access an index.

-Interrogatories

-Slip and Fall

-Conflict of Interest

-Husband-Wife Privilege

-Hospital

-Summary Judgment

-Fatal Car Accident

-Drug Overdose

-Plea Bargain

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

21C

§

2.5 COMMON RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The following are common questions almost always asked

in a beginning legal research course.

Where do I start and when do I stop?

Where do I start?

This one is easy. The researcher can start in any of many

research sources. There are encyclopedias, law reviews,

journals, statutes, regulations, cases, dictionaries, and many

other books that could be helpful. In most cases, there are

five sets of books which constitute the majority of materials

used to begin a legal research project. They are American

Law Reports, American Jurisprudence, 2d, Corpus Juris

Secundum, digests, and state or federal statutes

(depending on whether the issue is a state or federal matter).

There are certainly other books that the researcher may

utilize, but if the skills are developed to research within

these five sets of books, the student will have conquered

the majority of research skills needed in a law library.

When do I stop?

This one is not so simple. However, if the researcher has

thoroughly researched all the materials with which she or

he is familiar, or if the materials begin to lead to the same

cases and statutes, she or he can have some peace of mind

that the relevant material has been found. This exercise is

designed to introduce students to legal encyclopedias,

specifically American Jurisprudence, 2d and Corpus Juris

Secundum, the two national legal encyclopedias. At this

point, the goal is simply to get to know the books. Students

are not required to find specific on-point material at this

time. If one of the encyclopedias does not contain relevant

material to the assignment, don’t close the book. The student

should choose another topic, any other topic, that might be

of interest, enabling the student to be led to the main

volumes.

You should be aware that some law libraries only subscribe

to one of the above encyclopedias. Don’t let this worry you.

22

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Each encyclopedia is accessed in the same way, so if you

learn one, you learn both!

Remember, the goal at this point is to answer the

questions in the assignments on the following pages.

Students will not be able to do this without opening all the

relevant volumes in each set of books.

§

2.6 VISUALIZING THE BOOKS

Here’s a hint. Before leaving the library, sit down, close

your eyes and try to picture a page from Am. Jur. 2d in your

mind. Then try to picture the index for Am. Jur. 2d. Try to

visualize the supplement, etc. Then ask yourself the

following:

Can you visualize these tools in your mind? Are

you able to picture the differences between

them?

For instance, picture a page from C.J.S. as opposed to Words

& Phrases.

C.J.S.

- C.J.S. has commentary on most of the page.

- Within the commentary, there are small raised superior

numbers which refer to footnotes.

- The footnotes are at the bottom of the page.

- The footnotes contain citations to authorities.

Words & Phrases

- Words & Phrases has terms in bold face.

- Each term is followed by short paragraphs.

- The paragraphs are definitions of the term.

- Each paragraph also includes a citation.

By being able to visualize the form of the books, the function

is more likely understood. If a student can accomplish

this, it means she or he is beginning to understand the

materials.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

23C

§

2.7 PUBLISHERS:

A GAME OF MUSICAL CHAIRS

There are only two practical reasons to be able to identify the

publisher of a given set of books. First, if the publisher is the

government, the publication is official, and official cites come

first in any citation. The second reason is to be able to

identify whether the publication is part of a research system.

There are two major research systems. They were created

decades ago by two major publishers:

West Publishing Company

West, the largest publisher of legal materials, is

renowned for it’s Key Number System, a remarkably user

friendly system that allows the researcher to expand

his or her research by cross-referencing multiple digests.

The theory behind West’s research system is to get the

researcher to the law in a very efficient method.

Lawyer’s Cooperative Publishing Company

Lawyer’s Cooperative created the Total Client Service

Library (TCSL) research system with a different theory.

Unlike West’s system, which primarily leads to the law,

the TCSL provides practice aids to assist the researcher

in the representative process. The TCSL will lead the

researcher to additional materials, usually published by

Lawyer’s Cooperative. They include annotations, form

books, treatises, and other practice oriented materials.

The problem is that in the late 1990s, West Publishing

reorganized as WestGroup, which retained West Publishing

as a subsidiary, and purchased Lawyer’s Cooperative Publishing

Company as a separate subsidiary. Then, in the early 2000s,

WestGoup was obtained by Thomson Publishing Company.

However, in order to train the researcher in the two major

legal research systems, this book will refer to the original

publisher of legal materials, even though those original

publishers may now be owned by other corporate entities.

24

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

2.8 LIBRARY SCAVENGER HUNT ASSIGNMENT

Locate the following publications in the law library:

AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE, 2d

Index

Main Volumes

Supplement

CORPUS JURIS SECUNDUM

Index

Main Volumes

Supplement

REPORTERS (Your Regional Reporter)

Advance Sheet for Reporters

Any case

Headnote in a case

YOUR STATE STATUTES

Index

Main Volumes

Supplement (pocket part)

WORDS & PHRASES

Main Volumes

Supplement (pocket part)

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

25C

§

2.9 INTERACTIVE STUDY:

WORDS & PHRASES

Words & Phrases is a multi-volume legal dictionary by

West Publishing Company. It is different from other legal

dictionaries in that instead of simply providing a definition

for a term, Words & Phrases actually provides a quotation

from a court opinion that defines the term. If the researcher

finds relevant material, the quote that would be used

would be from the opinion, which is primary, instead of a

typical dictionary definition, which would be secondary.

The Volumes

Begin your Words & Phrases research in the main volume

containing the desired term.

Once the term you are researching has been located, it

will be provided in bold face type. Below the term the

researcher will find paragraphs which are actual quotes

from court opinions. There may be one , a few, or several

quotes provided. At the end of each quote is a citation to

the opinion being referred to. Once a desired quote has

been found, the researcher should locate the actual case

to cite it.

The Supplement

Check the corresponding term in the pocket part (also

called supplement) which is found in the back of each

volume.

As more recent definitions are created by courts, they will

be provided for in the supplement of each volume.

ASSIGNMENT 2.8A

Using Words & Phrases, research terms relevant to

your client’s situation and answer these questions.

1. How many volumes make up Words & Phrases?

2. Did you locate a relevant term?

3. Was your term updated in the supplement?

26

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Diagram 2(a): Screen Shot of Words & Phrases

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

27C

Diagram 2(b): Screen Shot of Encyclopedia & Index

28

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

2.10 INTERACTIVE STUDY:

AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE, 2d

Am. Jur. 2d is published by Lawyers Cooperative Publishing

Company, and is part of its Total Client Service Library.

American Jurisprudence, 2d is a national legal encyclopedia.

Legal encyclopedias provide at least a little information

about almost every area of law. The encyclopedias have

two basic goals:

To educate the researcher about a topic.

To lead the researcher to primary authority.

Am. Jur. 2d educates the researcher by commenting upon

an area of law. Within the commentary are footnote

reference numbers. (For instance: 13 ) These references

lead the researcher to the cases and statutes provided in

the footnotes at the bottom of the page, thus guiding him

or her to primary authority.

Am. Jur. 2d discusses the law and may be quoted, but it is

not the law. Therefore, Am. Jur. 2d is secondary authority.

_____________________________

The Index

Begin your Am. Jur. 2d research in the General Index.

The Am. Jur. 2d General Index is an excellent index.

The General Index can usually be found at the end of the

main volumes. It is a multi-volume, softbound index.

Since legal encyclopedias are arranged topically, the index

will lead us not to a volume and page number, but to a

topic and section number. (For instance, Depo § 273 in

the General Index would tell the researcher to find the

main Am. Jur. 2d volume covering the topic of Depositions,

and to turn within that topic to section 273.) If the

researcher doesn’t understand what a specific abbreviation

stands for, she or he should look at the beginning of a

main volume of Am. Jur. 2d. Many law books, including

Am. Jur. 2d, have abbreviation tables.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

29C

After looking up his or her topic in the General Index,

the researcher should observe whether there is a smaller,

single volume General Index Update. This is how the

General Index is supplemented, since softbound volumes

usually don’t have pocket parts.

ASSIGNMENT 2.9 A

Using the Am. Jur. 2d General Index, answer these

questions.

1. How many volumes make up the Am. Jur. 2d

General Index?

2. Is your research topic covered in the index?

yes

no

3. The Am. Jur. 2d Index leads to which of the

following?

a.

volume number, series, page number

b.

a topic and section number

c.

a topic and key number

4. Does the index have a supplement?

yes

no

5. If yes, where is it located?

6. Is your topic covered in the supplement?

yes

no

7. Provide any cites to the Am. Jur. 2d main

volumes the index may have provided.

30

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

The Main Volumes

The General Index leads the researcher to the main

volumes of Am. Jur. 2d.

After obtaining a topic and section number from

the General Index, the researcher must find the

main volume covering the topic. Then the specific

section number is found. After the section number,

Am. Jur. 2d will provide a boldfaced, short

statement of the subject matter for that section

number, followed by the discussion of the subject

matter. When reading the discussion, if any passage

is relevant, the researcher should refer to the

footnote which corresponds with the raised number

(footnote reference) in the discussion.

ASSIGNMENT 2.9 B

Locate the volume and section number which

the index provided, and answer these

questions.

1. What is the subject matter under your

topic and section number? There should be

a short, boldfaced statement.

2. Does the discussion provide any

footnote references?

yes

no

3. What kind of research assistance do the

footnotes provide?

4. Provide at least one case or statute from

the footnotes:

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

31C

The main volumes of Am. Jur. 2d have one other

feature that must be used with caution. It is a useful

tool called the Volume Index, or Title Index.

The Volume, or Title Index is many times more detailed

than the General Index. This makes it tempting for

the researcher to begin his or her research in the

Volume Index. The danger is that this index only covers

the specific area and volume being researched and

will (generally) only lead the researcher to material

within that specific volume. (Note that this index

only provides section numbers, not topics, since this

index is only for this volume.) Therefore, if there was

potentially critical authority under a different topic,

the researcher might never find it by using the Volume

Index alone. With these precautions in mind, the

researcher should use the Volume Index regularly, as

a supplement to the General Index. It is a very effective

research tool.

ASSIGNMENT 2.9 C

Within a main volume, locate the Title, or

Volume Index and answer these questions.

1. What is the topic of the Title Index you are

researching?

2. Are there any references to your research

assignment?

3. Does this index refer the researcher to

topics and section numbers, just topics, or

just section numbers?

topic & section numbers

only topics

only section numbers

4. Where does this index lead?

generally to a point within that

specific volume

generally to another topic or

volume

generally to other research sources

32

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

The Supplements

Supplements update the material within the

hardbound volume.

Remember, the purpose of Am. Jur. 2d is to lead the

researcher to primary authority, such as a case or

statute. However, before locating the primary authority

Am. Jur. 2d has cited, we must make sure that the

material researched is up to date. Am. Jur. 2d provides

supplements to its main volumes primarily in the form

of Pocket Parts. The researcher should research the

same Topic and Section number in the pocket part

that had been researched in the main volume.

Therefore, if Witnesses §§ 52, 67, and 127 were

researched in the main volume, Witnesses §§ 52, 67,

and 127 should also be researched in the pocket part.

The researcher should also be aware that if a pocket

part becomes too thick, the publisher may update

volumes by using a separate softbound supplement.

ASSIGNMENT 2.9 D

Locate the supplement in the volume you are

researching and answer these questions.

1. How does Am. Jur. 2d update material in

the volume you are researching?

2. Where does the researcher look in the

supplement?

under section numbers from the

Title Index only

corresponding topic and section

numbers

only corresponding section

numbers

3. Was there additional material for your

research topic in the supplement? If yes,

what kind of material?

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

33C

New Topic Service

Am. Jur. 2d’s New Topic Service provides

information on the most recent areas of law.

What happens if, after publishing, printing, and sending out

a new set of encyclopedias, Am. Jur. 2d decides a new area

of law deserves its own topic? For instance, when the AIDS

virus first became a matter of legal concern, cases and

discussions regarding AIDS were placed into various topics,

such as Physician & Surgeon, Diseases, etc. At some point,

the legal ramifications (of the AIDS health crisis) might be

broad enough to deserve their own topic. The publisher can’t

magically insert new topics into previously printed volumes,

so there must be a way for Am. Jur. 2d to provide the researcher

with this material.

The New Topic Service provides this information. It may be

found in two forms:

a 3-ring binder

a hard bound supplement

Whichever form it is found in, the New Topic Service is usually

kept at the end of the main volumes near the index.

ASSIGNMENT 2.9 E

Using the topic you have been researching, answer the

following questions.

1. Does your library contain the New Topic Service?

2. Is the New Topic Service in your library a hard

bound supplement or 3-ring binder?

3. Is there any new topic relevant to your research

assignment?

34

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

§

2.10a AM. JUR. 2D EXERCISE

1.

The Am. Jur. 2d Index leads to which of the

following?

a)

b)

c)

2.

3.

volume number, series, page number

a topic and section number

a topic and key number

Does the index have a supplement?

yes

no

How does the commentary refer to the

footnotes?

yes

no

4.

What kind of research assistance do the footnotes

provide?

5.

How does Am. Jur. 2d update material within the

main volume?

6.

Where does the researcher look in the

supplement?

__ under section numbers from the Title Index only

__ corresponding topic and section numbers

__ only corresponding section numbers

7.

What research system is C.J.S. a part of?

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

35C

Diagram 2(c): Screen Shot of Am.Jur.2d

36

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Diagram 2(d): Screen Shot of C.J.S.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

37C

The Constitution was not made to fit us like a strait jacket. In its elasticity lies

its chief greatness.

Woodrow Wilson

§

2.11 INTERACTIVE STUDY:

CORPUS JURIS SECUNDUM

C.J.S. is published by West Publishing

Company, and is part of its Key Number System.

Corpus Juris Secundum is a national legal encyclopedia.

Legal encyclopedias provide at least a little information

about almost every area of law. The encyclopedias have

two basic goals:

To educate the researcher

To lead the researcher to primary authority

C.J.S. educates the researcher by commenting upon an area

of law. Within the commentary are footnote reference

numbers. (For instance: 24 ) These references lead the

researcher to the cases and statutes provided in the

footnotes at the bottom of the page, thus guiding him or

her to primary authority.

C.J.S. discusses the law and may be quoted, but it is not

the law. Therefore, C.J.S. is secondary authority.

_________________________________

The Index

Begin your C.J.S. research in the General Index.

The C.J.S. General Index is an excellent index. The General

Index can usually be found at the end of the main volumes.

It is a multi-volume, softbound index. Since legal

encyclopedias are arranged topically, the index will lead us

not to a volume and page number, but to a topic and section

number. (For instance, Witn § 442 in the General Index

would tell the researcher to find the main C.J.S. volume

covering the topic of Witnesses, and to turn within that

topic to section 442.) If the researcher doesn’t understand

what a specific abbreviation stands for, she or he should

look at the beginning of a main volume of C.J.S. Many law

books, including C.J.S., have abbreviation tables.

38

Essential Skills for Paralegals: Volume II

Ours is a government of liberty by, through, and under the law. No man is

above it, and no man is below it.

Theodore Roosevelt

ASSIGNMENT 2.11 A

Using the C.J.S. General Index, answer these

questions.

1. How many volumes make up the C.J.S. General

Index?

2. Is your research topic covered in the index?

yes

no

3. The C.J.S. Index leads to which of the following?

a.

volume number, series, page number

b.

a topic and section number

c.

a topic and key number

4. Does the index have a supplement?

yes

no

5. If yes, where is it located?

6. Is your topic covered in the supplement?

yes

no

7. Provide a cite to the C.J.S. main volumes the

index may have provided.

Part One: Fundamentals of Research and Writing

39C

The Main Volumes

The General Index leads the researcher to the

main volumes of C.J.S.

After obtaining a topic and section number from the

General Index, the researcher must find the main

volume covering the topic. Then the specific section

number is found. After the section number, C.J.S. will

provide a boldfaced, short statement of the subject

matter for that section number, followed by the

discussion of the subject matter. When reading the

discussion, if any passage is relevant, the researcher

should refer to the footnote which corresponds with

the raised number (footnote reference) in the

discussion.

ASSIGNMENT 2.11 B

Locate the volume and section number which

the index provided, and answer these questions.

1. What is the subject matter under your topic

and section number? There should be a short,

boldfaced statement.

2. Does the discussion provide any footnote

references?

yes

no

3. What kind of research assistance do the

footnotes provide?

4. Provide at least one case or statute from

the footnotes:

40