Proof of the authenticity of a document in electronic format

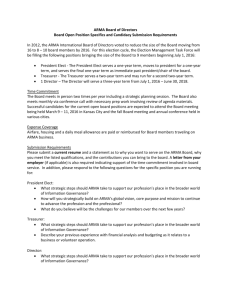

advertisement