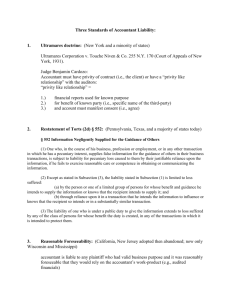

CN073 - Accountants' Liability

advertisement