Opening Brief - Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP

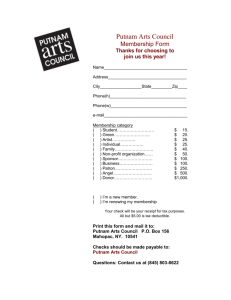

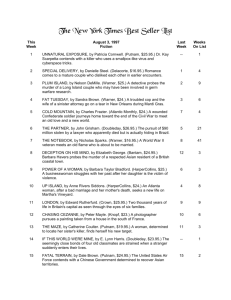

advertisement