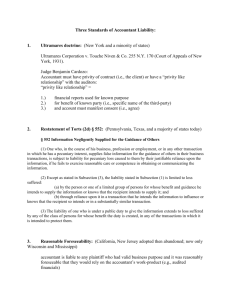

evolution of auditor liability to noncontractual third parties

advertisement