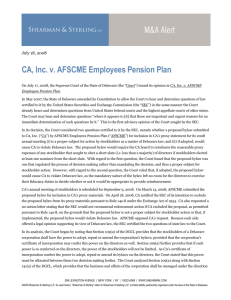

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE CA

advertisement