Social FranchiSing innovation and the power oF old ideaS

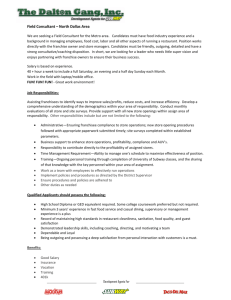

advertisement