A New Evaluation of Hernán Cortés's Textual Strategies in Light of

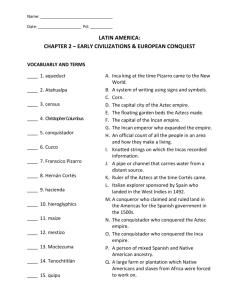

advertisement