Appendix V: Star Compensation

advertisement

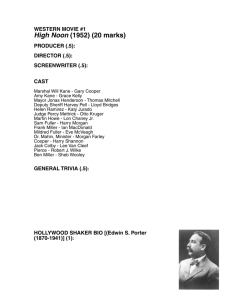

• There are two basic types of deals: gross and net participation. • In the former, participants are entitled to a share of the total revenues- or “rentals”“ t l ” received i d by b the studio in specified markets at various points in the film’s earnings. Appendix V: Star Compensation 714 • In its richest (and rarest) form, called “dollar one,” participants are entitled to a share of all the revenue received by the studio’s distribution arm Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 715 715 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • In Saving Private Ryan, Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg each had 16.75% of the revenues from the first dollar received (dollar one). This formula resulted in $30 million for each just from the theatrical distribution http://newsgrist.typepad.com/photos/uncategorized/ryan.jpg Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 716 716 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 717 717 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 1 • In most cases, gross participants are entitled to a share of the film’s revenues only after the film earns a specified amount or other requisites are met. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 718 718 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • So when Hanks and Spielberg got $30 million each for Saving Private Ryan, the film’s budget, which had been $78 million, million became $138 million. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 720 720 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • All gross participant payments are considered a deferred “production cost” and are retroactively tacked onto the budget of the film. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 719 719 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • By treating the stars’ share of the gross rentals as a production expense instead of as a distribution of the earnings, studios further push back the “breakeven” breakeven point at which less favored participants can begin to collect. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 721 721 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 2 • The contribution that stars make to a film’s earnings is more difficult to predict. • Leonardo DiCaprio appeared in g year: y three films in a single Titanic, The Man in the Iron Mask, and Celebrity. http://www.omnileonardo.com/pic s/t/html/tit201.jpg Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 722 722 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Titanic : $900 million in worldwide theatrical rentals, • The Man in the Iron Mask: $80 million • Celebrity: $3 $ million. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 724 724 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 723 723 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • DiCaprio could not, on its own, guarantee a large opening audience, even for two films that followed closely in the wake of Titanic. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 725 725 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 3 Julia Roberts (1997) • My Best Friend’s Wedding, earned $127.5 million in theatrical rentals • Everyone E Says S I Love You, earned only $12 million Terminator 3 • Arnold Schwarzenegger received a fixed fee of $29.25 million for Terminator 3 , $1.25 $1 25 million of perks, and 20% of all the gross revenues produced by the film worldwide after it reached its cash breakeven point. http://i.timeinc.net/ew/dynamic/imgs/031209/145249__ bestfriendswedding_l.jpg Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 726 726 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • The average earnings per film for the top ten stars of 2003 was roughly 30x what the equivalent stars had earned in 1948 under the old studio system (corrected for inflation). Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 728 728 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 727 727 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Stars also began creating their own personal production companies Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 729 729 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 4 • Tom Cruise’s production company, Cruise-Wagner Productions has coproduced several of his own moviessuch as Vanilla Sky, Mission Impossible, and The Last Samuraiand some of the movies made by his ex- wife, Nicole Kidman • Even when not acting as coproducers, stars often have the contractual power to choose, or block, many of the people who will work on a production http://news.bbc.co.uk/olmedia/675000/images/_677043_tom_150.jpg 730 730 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • In Terminator 3, for example, Schwarzenegger had the right to “preapprove” the director and the principal cast, his hairdresser, his makeup man, driver, his stand-in, his stunt double, the unit publicist, his personal physician, and his cook 732 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power732 in Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 731 731 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Most of these top stars also have had only limited formal education, having dropped g and even high g out of college school to pursue their careers. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 733 733 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 5 • Films that use outside financing must obtain essential-element element” insurance “essential on stars. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 734 734 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • If productions are unable to get such star insurance, they cannot get the completion bonds that banks and outside financiers require. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 736 736 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • While insurers cannot guard against all contingencies, they attempt to minimize their risk by refusing to insure actors who have a history of temperamental behavior, depression, risk taking, or other problems. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 735 735 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Hollywood writers’ book about Hollywood- such as Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon, Nathanael West’s The Day of the L Locust, Willi Faulkner’s William F lk ’ “Golden “G ld Land”- often expressed contempt, if not outright loathing, for the values of the studios. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 737 737 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 6 • The same contempt also pervaded movies about Hollywood: The Big Knife, The Bad and the Beautiful, Barton Fink, The Players, and State and Main, the studio is constantly portrayed as run by philistines maximizing their earnings on the back of the writer’s integrity. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 738 738 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Instead of being tethered to studios by seven-year contracts, stars are now auctioned off- with the help of savvy agents- to the highest bidder for each film. 739 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power739 in Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Since there are fewer super-stars than film projects, they can command eight-digit fees. • In this new era, stars, not studios, reap the profit their brand names bring to a film. 740 Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power740 in Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 741 7 Brand Name Stars Stars • Actors, directors • Characters(“James Bond”) • Creating stars requires major marketing investments. www.swschwedt.de/kunden/ bondnet/pictures/DrNo.jpg 742 The Star System • Well established in music and theatre since at least the 18th century. century • The world’s first movie star was Mary Pickford, mid-1910s. • Instead of attempting to brand the actors in the ppublic mind,, the studios of the early 1900s branded their products with their own names. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 743 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 Florence Lawrence http://www.geocities.com/Hollywood/Hills/2440/index-e.html 744 • The first celebrated movie actress, Florence Lawrence was Lawrence, referred to in press releases as “the Biograph Girl” while she worked for Biograph Pictures Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. 745 Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 8 • Brand-name actors were effectively the property of the studios, just as Mickey Mouse and Pluto. • In old Hollywood “studio” system, popular actor had long-term employment contracts. • Demise of the studio system after 19 0 made 1950 d stars essentially i ll free f agents whose salary reflects their market value. Epstein, Edward Jay, “The Big Picture, The New Logic of Money and Power in 746 Hollywood,” New York: E.J.E. Publications, Ltd., Inc., 2005 • Stars compensation based on bargaining strength. –John Travolta, when washed up got $140,000 for “Pulp l Fiction” –then jacked up his price to $10 million per film –2007: [ ] 747 http://www.kinoweb.de/film2001/FastAndTheFurious/pix/ffb.jpg Rewards for Actors http://www.rponline.de/layout/fotos/303x380/TRAVOLTA_ GEBURTSTAG_FRA505402cb47296d0.jpg 748 • Vin Diesel earned $700,000 for The Fast and the Furious, g hit and which was a huge made $143million at the box office • For his next movie, he commanded $10 million http://cinecover.free.fr/other/the_fast _&_furious_front2.jpg Grover, Ronald. “The Fast and Furious Spenders,” Business Week Online.5 October 2001. 749 9 • In addition, “Profit participations” began with a 1950 agreement between Jimmy Stewart and Universal •Stewart shared the film’s risk and profit www.dfwbands.com/ bands/jimmy_stewart.html 750 Do Financial Rewards Matter at the top? • Stars cannot afford to fail. • Gross participation contacts are only l weakk incentive i ti schemes h to t performance • But they are an incentive to participate in the marketing of a firm. 751 Are “stars” worth the money? But are “stars” worth the money? Two competing hypotheses: 1. Stars capture most of their value added. added 2. Stars are a “signaling device,” by which the producer signals the quality of the project to the studio, to outside financiers, and to reviewers. 752 753 http://www.aarrgghh.com/media/cash.jpg 10 • Star studded films bring in more revenues • Statistical studies show that stars or big budgets are associated with higher revenues but not with higher profits –Low budget films have higher 754 RoI. • A star’s presence by definition increases the expected revenue of a film, but it will not reduce the riskiness of ggross pprofits (unless the star takes substantial contingent compensation.) • Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. 756 Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 • Regression analysis of 200 films seem to show stars play no role in the financial success of a film. 755 • Star may be hired because the industry faces uncertainty and executives wish to be “covered” in case a project fails. • Executives may care about revenues and high visibility instead of profits, and big budgets predict revenues. 757 11 Leading Reason for overpayment of Stars • Star projects have better chance to gget funded 758 • Do media companies have an incentive to make the investment in performer’s f ’ career?? • Yes if long-term contract • • If selecting a given record is proportional to the fraction of previous consumers who picked it(a bandwagon effect), then the statistically predicted distribution off sales l levels l l for f “hit” records d closely matches the distribution of Record Industry Association of America Gold Records over three decades. 759 Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 The Old Hollywood Studio System http://tommymagazin.de/img/img_03755_2.jpg Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. 760 Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 • Studio could designate roles the actor was to perform, impose a change of name, name control the performer’s image and likeliness in advertising and publicity, and regulate interviews and public appearances. Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. 761 Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 12 N Long-Term Contracts • Used in the pop record industry. The artist performed exclusively for the studio for seven years, with the g the option p studio holding (exercisable every six or twelve months). • Either to renew the contract with an escalating salary or to terminate. • Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. 762 Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 TV Long-Term Contracts • TV show producers hire actors with an option on each actor’s services for five to seven years Litwak, Mark. Dealmaking in the Film and Television Industry. 763 Los Angeles: Silman James Press, 1994, p. 139 N –During this time, negotiations are shaped h d bby th the actor’s t ’ clout l t and the stipulations of a “favored-nations” clause. Litwak, Mark. Dealmaking in the Film and Television Industry. 764 Los Angeles: Silman James Press, 1994, p. 139 • If one actor negotiates better terms, every actor with a favorednations clause benefits. • Thus, Thus every actor enjoys the star’s “clout” as an essential performer. Litwak, Mark. Dealmaking in the Film and Television Industry. 765 Los Angeles: Silman James Press, 1994, p. 139 13 • Do superstars rise strictly on the basis of talent? • Much of it is fads and bandwagon effects. keanua-z.com/ webpix/tedlogan.jpg 766 • This means that superstardom might occur simply from a lucky accident, by acquiring some fans, whose choices are observed by other fans. Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. 768 Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 • Consumer uncertain about taste and quality. • Rational other people’s choices as a cheap indicator of likely quality. • Also consumer may simply get utility from following the popular style. Source: Caves, Richard E. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. 767 Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000 Stars and Superstars Model • In some areas (film, TV, sports, etc) small differences in talent result in extreme differences in reward • The minute talent differences are rewarded exponentially rather than linearly, resulting in a highly skewed distribution of rewards (be it money, professional commendation, etc…) MacDonald, Glenn M. “The Economics of Rising Stars”. The American Economic Review Volume 78 769 14 Applications of Star and Superstars Model • But this model isn't confined to entertainment industries • This Thi iis what h t often ft happens h in i media / IT / business in general, and its effect is just more pronounced in creative realms MacDonald, Glenn M. “The Economics of Rising Stars”. The American Economic Review Volume 78 770 Industry Structure and Talent • The labor market in business industries is remodeling itself the same way as it did in Hollywood –In old Hollywood, y actors and directors would work for 1 studio for a set number of years –Much like the employer-employee relationship in the past 772 DeVany, Arthur. “Contracting with stars when “nobody knows anything”. Hollywood Economics 2004 Creative Industry Structure: Hollywood • Like most creative industries, Hollywood is a kurtocracy… • …a few individuals have immense power andd wealth lh • This elicits the question “what caused it and why does it stay that way?” DeVany, Arthur. “Contracting with stars when “nobody knows anything”. Hollywood Economics771 2004 Industry Structure and Talent • Now, in Hollywood as in the creative business realms, a group assembles itself for 1 project –A A studio might partner a producer, director, and an actor make 1 movie together –Just like companies now partner contract workers, consultants, and 773 outsourced vendors DeVany, Arthur. “Contracting with stars when “nobody knows anything”. Hollywood Economics 2004 15 Industry Structure: Business and Hollywood What’s an Oscar worth? • The key similarity is that after the assigned project, neither the film industry or business employees are contractually ll bound b d to stay with the same firm / studio • This is a marked shift from the old more restricted structure • 60% of best actor and actress Oscar winners from the past 10 years have seen how their earnings drop off after their victories. Brandon Gray, Career builders? Why Oscar wins don’t always translate into box office success for actors and actresses, February 27, 2006 DeVany, Arthur. “Contracting with stars when “nobody knows anything”. Hollywood Economics 2004 774 What’s an Oscar worth? http://theenvelope.latimes.com/movies/boxoffice/env-boxofficeactoractress27feb27,0,6035517.column 775 WHAT'S AN OSCAR WORTH? • Most of the winners are already big stars, and an Oscar has rarely turned a new artist into a big star. Box office results for best actor/actress winners (Averages for the 5 movies before and after a win) Pre-Win Post-Win Career Actors Average Average Average 2004 Jamie $47,387,483 Foxx $49,365,952 (2 movies) $37,366,764 Hilary Swank $42,302,893 - $33,138,550 Brandon Gray, Career builders? Why Oscar wins don’t always translate into box office success for actors and actresses, February 27, 2006 http://theenvelope.latimes.com/movies/boxoffice/env-boxofficeactoractress27feb27,0,6035517.column 776 Box Office Mojo, LLC (www.boxofficemojo.com) 777 16 Actors 2003 Sean Penn Charlize Theron Pre-Win Average Post-Win Average Career Average $$24,474,359 , , (3 movies) $20,071,498 $14,871,122 $31,091,072 (3 movies) $26,948,066 $29,955,962 Box Office Mojo, LLC (www.boxofficemojo.com) 778 Pre-Win Post-Win Career Actors Average Average Average 2001 Denzel $70,097,169 $70 097 169 $55,558,239 $55 558 239 $40 $40,148,074 148 074 W hi t Washington Halle Berry $59,467,313 $118,947,198 $57,355,360 Box Office Mojo, LLC (www.boxofficemojo.com) 780 Actors 2002 Adrien Brody Nicole Kidman Pre-Win Average Post-Win Average Career Average $7,104,705 $24,190,899 $22,788,399 $51,283,814 $33,426,697 $43,924,752 Box Office Mojo, LLC (www.boxofficemojo.com) Pre-Win Actors Average 2000 Russell Crowe $58 063 118 $58,063,118 Julia Roberts $112,212,578 Post-Win Average 779 Career Average $89,729,776 (4 movies) $43,359,633 $43 359 633 $72,478,084 $72,203,091 Box Office Mojo, LLC (www.boxofficemojo.com) 781 17 What’s an Oscar worth? • Box office revenues might not have gone down because stars had the freedom to pursue smaller i d independent d t films. fil – Philip Seymour Hoffman – Charlize Theron 782 • How should Disney assess the risk of hiring stars for its projects? • How should it compensate stars? 783 783 18