Hamlet Soliloquy #6 Analysis: Revenge & Inaction

advertisement

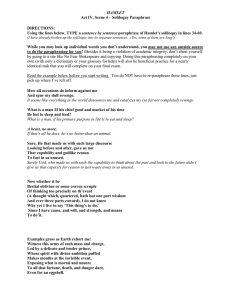

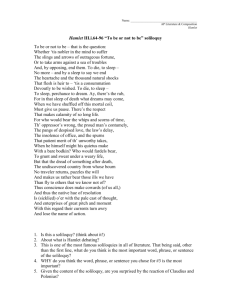

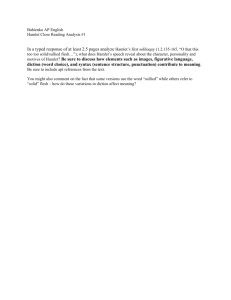

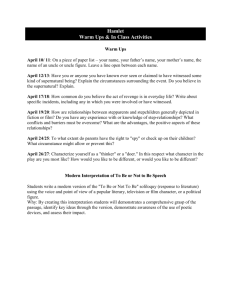

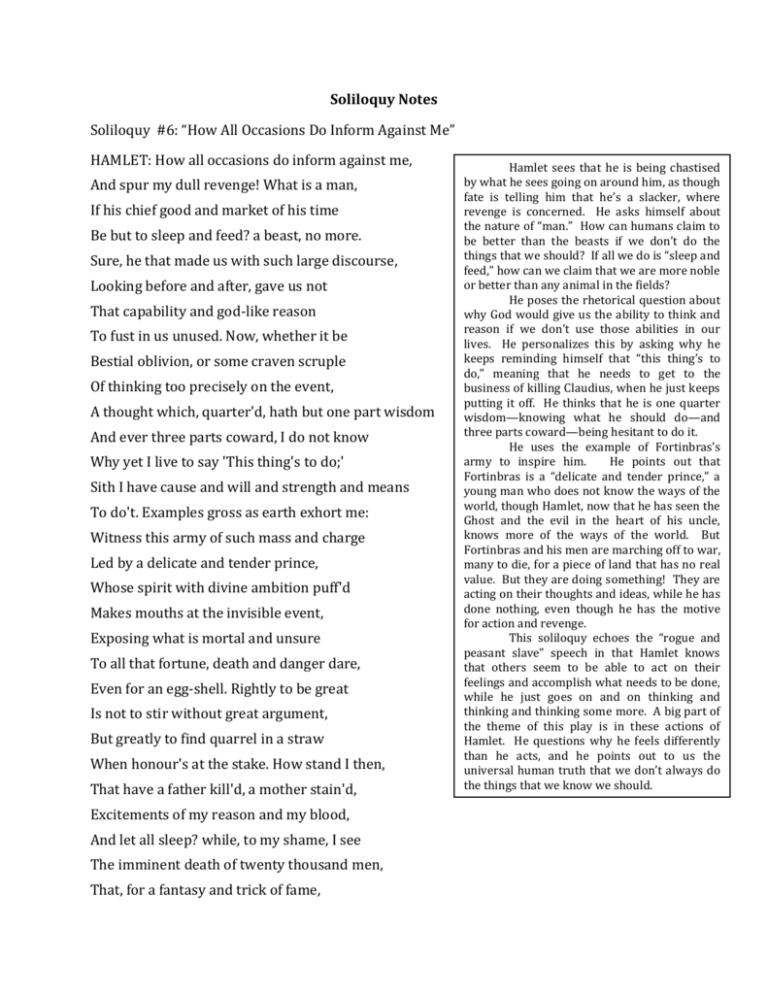

Soliloquy Notes Soliloquy #6: “How All Occasions Do Inform Against Me” HAMLET: How all occasions do inform against me, And spur my dull revenge! What is a man, If his chief good and market of his time Be but to sleep and feed? a beast, no more. Sure, he that made us with such large discourse, Looking before and after, gave us not That capability and god-like reason To fust in us unused. Now, whether it be Bestial oblivion, or some craven scruple Of thinking too precisely on the event, A thought which, quarter'd, hath but one part wisdom And ever three parts coward, I do not know Why yet I live to say 'This thing's to do;' Sith I have cause and will and strength and means To do't. Examples gross as earth exhort me: Witness this army of such mass and charge Led by a delicate and tender prince, Whose spirit with divine ambition puff'd Makes mouths at the invisible event, Exposing what is mortal and unsure To all that fortune, death and danger dare, Even for an egg-shell. Rightly to be great Is not to stir without great argument, But greatly to find quarrel in a straw When honour's at the stake. How stand I then, That have a father kill'd, a mother stain'd, Excitements of my reason and my blood, And let all sleep? while, to my shame, I see The imminent death of twenty thousand men, That, for a fantasy and trick of fame, Hamlet sees that he is being chastised by what he sees going on around him, as though fate is telling him that he’s a slacker, where revenge is concerned. He asks himself about the nature of “man.” How can humans claim to be better than the beasts if we don’t do the things that we should? If all we do is “sleep and feed,” how can we claim that we are more noble or better than any animal in the fields? He poses the rhetorical question about why God would give us the ability to think and reason if we don’t use those abilities in our lives. He personalizes this by asking why he keeps reminding himself that “this thing’s to do,” meaning that he needs to get to the business of killing Claudius, when he just keeps putting it off. He thinks that he is one quarter wisdom—knowing what he should do—and three parts coward—being hesitant to do it. He uses the example of Fortinbras’s army to inspire him. He points out that Fortinbras is a “delicate and tender prince,” a young man who does not know the ways of the world, though Hamlet, now that he has seen the Ghost and the evil in the heart of his uncle, knows more of the ways of the world. But Fortinbras and his men are marching off to war, many to die, for a piece of land that has no real value. But they are doing something! They are acting on their thoughts and ideas, while he has done nothing, even though he has the motive for action and revenge. This soliloquy echoes the “rogue and peasant slave” speech in that Hamlet knows that others seem to be able to act on their feelings and accomplish what needs to be done, while he just goes on and on thinking and thinking and thinking some more. A big part of the theme of this play is in these actions of Hamlet. He questions why he feels differently than he acts, and he points out to us the universal human truth that we don’t always do the things that we know we should. Go to their graves like beds, fight for a plot Whereon the numbers cannot try the cause, Which is not tomb enough and continent To hide the slain? O, from this time forth, My thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth! He sees the futility of Fortinbras’s campaign against the Poles. They are going to fight for a piece of land that, if won, will not be big enough to house all of their graves. There is no way that this battle is worth the deaths that will come from it. Yet they are doing something! And Hamlet has to admire that. Again, he reiterates that the example of Fortinbras’s army has brought back his resolution to get his uncle and exact his revenge. He will have the “bloody” thoughts in the future so that he can accomplish what needs to be done here and now.