Positive energy A review of the role of artistic activities in

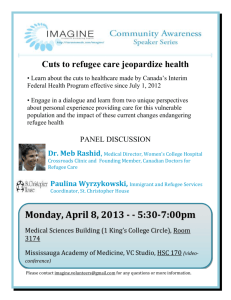

advertisement