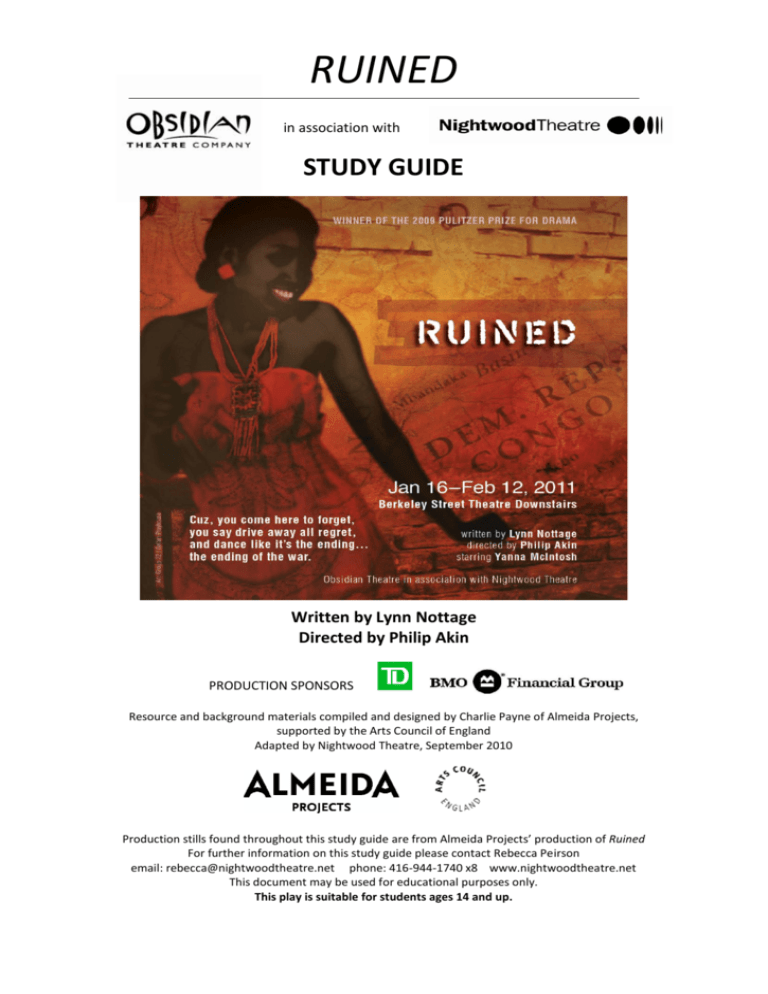

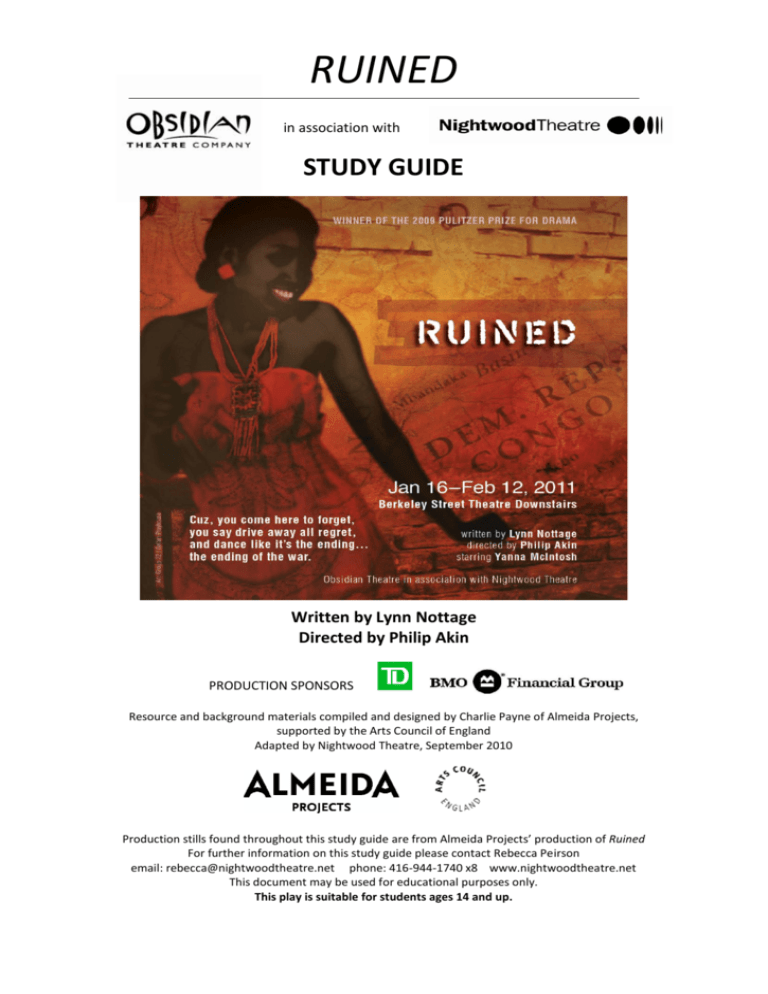

RUINED

in association with

STUDY GUIDE

Written by Lynn Nottage

Directed by Philip Akin

PRODUCTION SPONSORS

Resource and background materials compiled and designed by Charlie Payne of Almeida Projects,

supported by the Arts Council of England

Adapted by Nightwood Theatre, September 2010

Production stills found throughout this study guide are from Almeida Projects’ production of Ruined

For further information on this study guide please contact Rebecca Peirson

email: rebecca@nightwoodtheatre.net phone: 416-944-1740 x8 www.nightwoodtheatre.net

This document may be used for educational purposes only.

This play is suitable for students ages 14 and up.

CONTENTS

The Play

Introduction

Characters

Play synopsis

Production & Creatives

Cast and Creative Team

About Nightwood Theatre

About Obsidian Theatre

About Lynn Nottage

Lynn Nottage on Ruined

Interview with Philip Akin

15

16

16

16

17-18

19-20

Context

DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo

Women and the Conflict

Rape: A Weapon of War

Conflict Minerals in the DRC

The Ituri Conflict

Places in Ruined

21-22

23-24

25-26

27

28

29-30

Exploratory

Practical Exercise One

Practical Exercise Two

Practical Exercise Three

Practical Exercise Four

Script Extract #1

Script Extract #2

Further Reading

31

31

32

32

33-35

36-37

38

Credits

Almeida Projects

2

3

4-5

6-14

39

INTRODUCTION

Ruined was written by Lynn Nottage in 2007 and awarded the 2009

Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Ruined involves the plight of a group of women in the

civil war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo. Set in

Mama Nadi’s bar - a haven for miners, government

soldiers and rebel militia, where they come to forget the

ruins of war, to drink and dance with women and feed

their desires. The play centres on the lives of the women

working in the bar and their resolve to survive despite

the atrocities they have experienced.

Two new girls arrive at Mama Nadi’s bar, both recent

victims of militia violence. Mama reluctantly agrees to

take them in, and she puts them to work. As the conflict

around the bar intensifies, the women continue to

entertain their male customers. But as loyalties become

divided as the conflict fragments, Mama’s attempts to

shelter the women from the dangers outside threaten to

put their lives - and Mama’s business - in jeopardy.

The Democratic Republic of Congo has a long history of civil war and brutal conflict. The

country has, in recent years, become a centre for mining valuable minerals including coltan,

which is used in the manufacture of mobile phones and the technology the West takes for

granted. The systematic rape of women - often extremely violent - has become a chief

instrument of war, used both as a means of ethnic cleansing and tribal intimidation. This is

the backdrop against which the play was written.

Ruined was commissioned by Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, where it received its world

premiere in a co-production with New York’s Manhattan Theatre Club. In writing the play,

Lynn Nottage travelled to the Congo with director Kate Whoriskey, interviewing women who

had directly experienced sexual violence. The play was initially intended to be an update of

Brecht’s Mother Courage, transposed to the Congo; but as Nottage heard more and more of

the women’s stories, the Brecht connection became significantly less important and Ruined

became a story of the women of Congo first and foremost.

3

CHARACTERS

MAMA NADI

An attractive woman in her early forties, proprietor of Mama Nadi’s bar. She has an arrogant

stride and a majestic bearing. She can be flirtatious to get her way and knows how to charm

men in the system - an excellent business woman. She has a dark and troubled past which

gives her a definite hard edge and steely toughness, but it also gives her an empathetic

compassion for ‘ruined’ women - she takes in women who have been raped by soldiers and

offers them a livelihood.

CHRISTIAN

Christian is a travelling salesman, trafficking goods across the border for businesses in the

war-torn parts of the Congo. He has a fondness for philosophising and poetry - hence

Mama’s nickname for him: ‘the professor’. He despairs at the unpredictable conflict tearing

his country apart and the ignorance of the young men who claim authority. He is in love

with Mama and wants to settle down with her.

SOPHIE

Sophie is a beautiful girl, aged 18. She was a very good student and preparing to take her

university entrance exams. However she has been outcast by her village, after suffering

some terrible and brutal abuse from the militia - she has been ‘ruined’, genitally mutilated.

She is gentle and very compliant at first, but has a steely determination and sense of survival

which ultimately drives her to start deceiving the very woman who took her in.

SALIMA

Salima, also 18, is rather a plain girl with a stubbornness and defiance. She too has been

attacked by militia men, who raped her, before abducting her and keeping her as their

‘concubine’ in the forest. Her husband has refused to take her back and she has been exiled

from her village. She holds out hope that her husband will come back for her.

JOSEPHINE

A prostitute at Mama Nadi’s bar. She is resentful of the newcomers and makes little attempt

to befriend them. Mr Harari regularly comes to see her, and she hopes he will take her out

of the bar, eventually. Her father was the village chief and she was eldest born child. She

was attacked by soldiers at her home but none of the villagers came to her aid.

JEROME KISEMBE

Jerome Kisembe is leader of the local rebel militia. He is a powerful man and dangerous,

with an unpredictable, volatile temper. He commands a band of men known for their violent

demanding of respect. He opposes the ‘unjust’ rule of the government, tackling violence

with violence. He is a regular customer at Mama Nadi’s bar.

COMMANDER OSEMBENGA

He is high in the government, charged with bringing the area surrounding Mama Nadi’s bar

back into law and order. He is seeking out the rebel militia and destroying their army. He is a

brash, loud man, commanding instant respect, but with a volatile temperament and violence

concealed ever below the surface of his presence. He is a man used to getting what he

wants without having to ask twice.

4

MR HARARI

Mr Aziz Harari is a gemstone trader from the Lebanon, in the Congo on business. He has

been coming to Mama Nadi’s bar for some time and has built up a relationship with

Josephine, though this is really no more than a business transaction. He is a gentle man,

offering Mama advice and his wisdom as an outsider. He seems at once frustrated and

bemused by the desperate situation he perceives in Congo.

FORTUNE

Fortune is Salima’s estranged husband. He was a farmer before being enlisted to the

government army and is not happy with the soldier’s life. He disowned Salima following

her attack but now seeks her forgiveness as he still loves her and is full of regret. He stakes

his place outside Mama Nadi’s and threatens his safety by waiting for his wife.

SIMON

Simon is Fortune’s cousin, and they grew up in the same farming village. He has known

Salima since childhood and is accompanying his friend to look for his wife, though he does

not believe she is still alive. He too was a farmer but has joined the government army and is

loyal to Commander Osembenga.

LAURENT

Laurent is a young and hard-faced government soldier, working closely with Commander

Osembenga. He is quick to carry out his boss’ orders and execute violence where directed.

5

PLAY SYNOPSIS

ACT ONE

SCENE ONE

A small mining town in the Democratic

Republic of Congo. It is mid-afternoon at

Mama Nadi’s bar, a worn-looking

establishment; nonetheless a lot of effort

has gone into making it look cheerful.

Mama Nadi is there, serving a cold drink

to Christian. Christian has been on the

road for a long time - many of the roads

are impassable with blockades - and

having reached Mama Nadi’s, relaxes. He

has brought Mama Nadi some provisions

she requested, including a red lipstick. He

flirts playfully with her, it is clear they are old friends. Mama Nadi offers Christian a beer, but

he declines - he has not drunken alcohol for 4 years. Christian notices the caged parrot,

which belonged to a now deceased village elder. The bird annoys Mama Nadi - it speaks a

pygmy language that no one understands. Christian tells Mama Nadi he has something else

for her, and she guesses correctly - he has brought her girls. But three - and she cannot make

room for three. Christian offers to give her a good price, reassuring her that business is

good. Mama insists on taking just the one and they haggle about the price. They agree and

Mama chooses one of the women. She instantly picks out Sophie, and Christian then offers

Mama two girls for the price of one - she can take Salima as well. Mama is adamant that she

will only pay for one - and this is exactly as Christian would have it. Mama is bemused, but

accepts.

Mama calls Josephine, one of her girls, a sexy

woman in a short skirt. Josephine surveys the

two new girls with obvious contempt, but

Mama orders her to take the girls to be

washed and clothed. Before they go, Mama

inspects Salima and Sophie a little closer,

sensing them fit for business. Salima is at once

nervous and defiant. Sophie is compliant but

we see her walking with some pain.

Christian tells Mama about Salima’s past - she

is from a tiny village that has disowned her - her husband won’t take her back after being

raped by soldiers. Sophie, he tells her hesitantly, is ruined. Mama is furious that Christian

has brought her a ruined girl - she’s paid for another mouth to feed and a burden - though

she is pretty, she is useless to Mama. Christian urges Mama to keep Sophie, who has been

treated appallingly by the militia. Mama dismisses this as outside her responsibility but

Christian reassures her that Sophie is a good girl and will work hard, she can clean and sings

like an angel. He offers her anything she wants off his truck if she agrees, even Belgian

chocolate. He reveals that Sophie is actually his sister’s only daughter.

6

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

Mama calls Sophie back to inspect her closely. She quizzes the young girl and we discover

that Sophie was a good student and about to sit for her university exams, before the soldiers

hurt her. A ruined woman brings shame on the village, so her future was changed. Mama

agrees to take Sophie in and then questions her about her skills - she can sing, and do math.

Mama puts red lipstick on Sophie and admires her beauty. She gives Sophie a drink of liquor

to help her pain down below. Christian gives Mama the Belgian chocolates - she eats,

savouring every bite. Mama offers Sophie a chocolate, but not Christian. This amuses Sophie

but she is quickly subdued when Christian gives her a warning - many men would have left

her for dead. Before her uncle leaves, she promises to be a good girl for Mama.

SCENE TWO

A month later, at Mama NadI’s bar. Colourful Christmas lights give a festive atmosphere and

the bird still sings raucously from the back. At the bar, drunk and disheveled soldiers drink

beers and laugh loudly, at the centre of the group is Jerome Kisembe, the rebel leader

dressed in military uniform. Salima, dressed attractively, is playing pool as the soldiers look

on. Mama circulates the bar, wearing a red scarf, acknowledging the rebel leader’s colours.

Meanwhile, Josephine is lap dancing for Mr Harari, a Lebanese diamond merchant. Sophie

sings. The song finishes and the soldiers ask for another, calling her over, but she ignores

them. One soldier calls Mama over and shows her a lump of coltan he stole from a miner. He

is proud of his steal, but Mama dismisses it as worthless not - there are too many

prospectors, there’s no more money in coltan. The soldier grows increasingly belligerent as

Sophie ignores him and Mama won‘t take the coltan as payment for a girl. Mama intervenes

and takes his coltan, offering him Salima - the soldier wanted Sophie, but Mama assures him

Salima is the better dancer. They dance.

Sophie, relieved, sings another song about

the war. Mr Harari talks to Josephine

about Sophie. Josephine tells him that

Sophie’s ruined - the other girls think she

brings bad luck. Mr Harari asks Josephine

to put on the dress he had brought her.

Whilst Josephine is changing, Mama asks

Mr Harari where his shoes have gone. He

tells her that a young rebel soldier stole

them - this has happened before. Meanwhile Salima struggles briefly with the soldier, who is

getting overly friendly. Mr Harari reviews the situation; he chides Mama for taking the man’s

coltan - he knows how much money that would fetch on the market, and cautions Mama

against getting involved in that business. She dismisses his concerns - she cannot understand

the fuss about coltan. Mr Harari explains how valuable it is in the age of mobile phones.

Mama shows him some gems she has procured, including a raw diamond, and Mr Harari sets

about valuing them - mostly worthless, but the raw diamond might make some good money.

Mama compares Mr Harari to her father; we discover Mama’s father used to have a farm,

before it was taken by a white man. She tells him how important she feels property rights

7

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

are - that land is what she wants. But this is not easy in Congo, without picking up a gun. Mr

Harari would love to help find an answer to Mama’s wishes, but demurs that he cannot even

hold onto a pair of shoes in the country - let alone land. He criticizes the fickle nature of

militia politics in the civil war, Mama agrees, but concedes that even the militia need

entertainment.

Josephine returns in the new dress. Mr Harari admires her beauty and even suggests he

might have to take her home with him, when he leaves Congo.

Jerome shouts Mama over - he orders more beer and complains at the lack of mobile phone

reception in the bar.

Josephine tells Mr Harari about Jerome - he’s fearless, the boss man, and dangerous.

Salima finally pushes the soldier away and makes for the door. Mama pulls her back in and

makes her return to the soldier. Sophie asks if she is ok - the soldier bit Salima and she is

upset and does not want to go back to him. Sophie urges that she must.

SCENE THREE

Morning, in the bar’s living quarters. Sophie is painting Salima’s fingernails with Josephine’s

nail polish - they have to rush before she returns. Sophie senses there is something wrong

with Salima, and questions her. Salima is frustrated and angry at having to work in the bar

and be treated badly by soldiers. The soldier had told her that some men had been shot, and

she thinks one of them could have been her brother. She says she misses her family, but

Sophie silences her - they promised not to talk about home. But Salima continues, saying

aloud the name of her baby; she wants to go home. Sophie sets her straight - they cannot go

home. Where will they go? The village has thrown them both out and it isn’t safe for a

woman alone. Sophie talks of her physical pain - every step she takes is a reminder of her

attack by the militia men, and the pain will never leave.

Salima tells Sophie that she is pregnant. She cannot tell Mama, who will likely turn her out.

Sophie shows Salima a stash of money she has been hiding from Mama, taking it from the

bar takings and adjusting the books. Sophie tells Salima they won’t be at the bar forever, and

swears her to secrecy.

Josephine returns and the girls bicker. She reveals an enormous black scar circumventing her

stomach and comments that Salima is looking fatter. Salima and Josephine argue. Sophie

tries to placate Josephine and they listen to a report on the radio, talking of more civil

unrest. Josephine tells the girls that she is going to the city with Mr Harari next month. She

provokes Salima more by referring to her family. Salima runs out and Josephine turns on

Sophie, jealous of her beauty and seeming dignity. She tells Sophie that she is worse than a

whore, she is ruined. She tells Sophie that she was attacked because her father was the

village chief, and no one in the village came to her aid, they looked the other way.

8

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

SCENE FOUR

Dusk in the bar, bustling with activity. Sophie sings, as Salima and Josephine talk with men.

Christian enters, to surprise Mama. She gets him a soda and gives him a list of requests Sophie has helped her write this. He tells Mama about his latest mission, and that the white

pastor has been missing for some

days. Rumour has it he had been

treating rebel soldiers and upset local

militia. The militia are battling with

each other for control of the local

area, it is a dangerous time for

everyone.

Christian asks Mama to become his

lover and business partner, they

could move to a city and start again.

She dismisses his ideas and proposal she has her own business. Christian tells her she is too proud and stubborn. He asks for a

dance. Mama chides his foolishness.

Just then the Commander Osembenga struts into the bar, a rival militia leader with a

pompous stride and dark sunglasses, with a pistol at his side. He is accompanied by a

Government Soldier in uniform. Christian stops dancing and nods deferentially. Mama

welcomes him in and brings him a drink, though she asks him to leave his bullets at the bar house rules, no matter who he is.

Mama asks him what brings him to the bar. The

Commander tells her he is after Jerome Kisembe.

Mama denies knowing him personally, not

mentioning that he is a customer. The Commander

tells her Jerome is a dangerous man, and talks about

his crimes as a rebel leader committed in the name of

peace and reconciliation. He reveals his name, as the

new boss man; Mama pours him a glass of her finest

whiskey from the United States, taking great care of

this important man. He issues a veiled threat to

Mama: she is a practical woman, and knows better to

allow rebel soldiers through her door. Mama agrees,

and beckons over Josephine and Salima to entertain

the Commander. She leaves the table. Christian urges

her to be cautious with the Commander.

The Commander calls Mama over and asks about

Christian. Mama assures him Christian is harmless.

The Commander buys Christian a whiskey. Christian is

in a dilemma - he urges Mama not to make him drink,

he has not had a drink for 4 years and must refuse; but Mama knows the danger of refusing

this gesture from the Commander. Christian drinks.

9

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

SCENE FIVE

Morning in the bar. Sophie is reading to Josephine and Salima from a romance novel. The

listening girls are rapt. Mama enters with her lock box of money and breaks up the gathering

- she tells the girls she does not care for romance, as she knows already of the unsatisfactory

ending. Salima spots a man approaching the bar, Mr Harari. Salima and Sophie tease

Josephine about Mr Harari. Josephine rounds on Sophie, reminding her that she is ruined

and men want a women who is complete - something Sophie will never be. Sophie is upset

and Mama sends Josephine out. She tells Sophie to stand up to Josephine.

Alone with Sophie, Mama asks her to count last night’s takings. Sophie begins. She finds

Mama’s rough diamond in the box and asks about it. Mama tells her it is her insurance policy

against the war. Sophie suggests to Mama that she could charge a little more for beer, so

they could buy a new generator. Mama admires Sophie’s quickness with numbers and asks

her if she has indeed counted everything. Sophie says she has but Mama reaches inside

Sophie’s top and produces the bundle of notes hidden there. Angry, Mama threatens to

throw Sophie out onto the street. But Sophie tells her why she is saving - there is an

operation available to repair the damage on her body inflicted by the soldiers. Mama

relents. She takes the money from Sophie and puts it back in the box, congratulating her on

being the first girl bold enough to steal from her.

SCENE SIX

In the bar, the next morning. Josephine is struggling with a drunk miner, whilst Salima

sneaks food from under the bar. Christian enters, winded and on edge, covered in dirt.

Mama comes to greet him. Christian tells her the white pastor has been killed by

Commander Osembenga’s soldiers, brutally cut up beyond recognition. Christian asks for a

whiskey and Mama is surprised. He gulps down the

whiskey and talks about the murder, there were no

witnesses and nobody seems to know anything. He

criticizes the militia - ignorant country boys who don a

uniform and assume control. He demands another

whiskey - not a Fanta. He knows that killing a missionary

means bad things for the conflict. Mama dismisses this another dead man, but she still has a business to run but she seems overwhelmed. Christian asks Mama to

leave with him, to go to Kinshasa, set up a business, the

two of them. Mama isn’t convinced.

Suddenly two ragged soldiers, Fortune and Simon,

enter, in ill-fitting uniforms with tatty weapons. Fortune

is carrying an iron pot. They are very on edge. They ask

if this is the place of Mama Nadi - she in turn confirms

this. They ask for a meal and a beer and she demands

10

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

that they empty their weapons and they agree. Sophie enters, noticing the soldiers and the

caution in the atmosphere. The soldiers greet her politely. Sophie goes to bring water for the

soldiers to wash up.

Mama enquires after the soldiers’ origins. They tell her they fight for Commander

Osembenga. Fortune asks Mama if Salima is here. Christian starts to answer but Mama cuts

him off, asking why the men are looking for her. Fortune gives a description of Salima,

convinced Mama is hiding her - he is Salima’s husband. Mama coolly tells him she will

enquire inside, and exits into the back. Simon reassures his friend that they will find his wife.

A man on the road had described Salima and they are convinced that she is at Mama Nadi’s.

Mama re-enters and tells the soldiers that no one has heard of Salima: the soldiers are

mistaken looking for her here. Fortune accuses Mama of lying - he is adamant she is here. He

tells Mama to tell Salima that he will be back for her, and the men leave. Christian scolds

Mama with his eyes.

ACT TWO

SCENE ONE

Fortune stands outside the bar, waiting. Inside,

the girls entertain drunk customers, soldiers

and a miner. Mama and Sophie sing: despite

the atrocities of war, the door never closes at

Mama‘s place. Josephine dances, beginning

playfully; but her dancing becomes more frenzied as she releases her anger. Overwhelmed,

reliving her attack in a painful flashback, she claws at the air. Sophie goes to her aid.

Meanwhile, Christian is at the bar, drunk and struggling to remain upright.

SCENE TWO

In the back room at the bar. Josephine sleeps. Salima is looking at her pregnant stomach

and, as Mama enters, quickly hides it under her clothing. Mama asks Salima to go out and

entertain the customers. She is reluctant, so Mama wakes Josephine, who obliges, in a bad

mood at being woken. Salima asks Mama if Fortune is still outside. Mama tells her that he is.

Salima cannot understand why he won’t leave - she doesn’t want him to see her. Sophie

knows he won’t leave until he sees her - she believes he still loves her. But Mama coldly

dismisses the romance of this idea - one day, it will turn bad, the questions will come, a man

not understanding the violation of his wife by other men. Sophie argues but Mama reminds

her that Fortune left Salima for dead: this is her home now. The simple life the girls

remembered in the village has gone now. Mama tells Sophie she has read too many

romance novels.

Salima cries. Mama goes to send Fortune away. Sophie urges Salima to talk to Fortune, but

Salima resists, as Fortune does not know she is pregnant. Salima recounts the story of her

brutal attack by the soldiers to Sophie, which happened whilst Fortune was buying her a

new cooking pot. The soldiers gang-raped her in the garden and killed her baby by stamping

11

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

on its head. Nobody in the village came to her aid. Salima recalls the moment just before the

attack, before everything changed. She tells Sophie that the baby she is pregnant with is not

Fortune’s. She remembers with pain how his family disowned her after the attack - Fortune

beat her ankles. She cannot see him now.

SCENE THREE

Fortune stands outside the bar in the rain. Mama comes out and advises him to leave - the

woman he is looking for is not here. Fortune tells Mama to tell Salima that he loves her. He

gives Mama the iron cooking pot for her - it is the pot he had gone to town to get on the day

of her attack. Mama scorns his gift, once again telling Fortune to leave, as two drunk

government soldiers tumble out of the bar.

Josephine comes out to call the soldiers back, but they leave. Simon appears for Fortune, out

of breath. He tells Fortune that Commander Osembenga is gathering his forces and they will

be moving on to the next village tomorrow. They have to leave, but Fortune cannot bring

himself to leave Salima. Simon will go inside with Josephine and try to find Salima and have

some fun at the same time. Fortune is repulsed at the idea. Simon tells him to give up on

Salima - if Fortune stays, he will be killed by the rebel militia, and his fellow soldiers are

mocking him, chasing his ‘impure’ wife. This last makes Fortune angry and they struggle,

briefly. Simon tells Fortune to be angry at the men who took his wife instead of him, and

urges him to kill the rebels to avenge them. Fortune is troubled, he just wants his wife and

family back. Simon leaves with a warning that they have been ordered to kill all deserters he tells his friend Salima is gone.

SCENE FOUR

The bar. Christian, drunk, recounts a story of

the violence of war and the evil of Commander

Osembenga. Mr Harari, Mama and Sophie

listen, until Mama quietens Christian - his

opinions are dangerous.

Two rebel soldiers enter from the back, with

Josephine and Jerome Kisembe following.

Jerome is on edge. He pushes Josephine away.

Mama greets Jerome who tells her that

Commander Osembenga has been giving the rebel militia trouble, having set fire to several

of their villages, and take machetes to anything that moves. The rebels have been forced

deeper into the bush. Josephine spots Mr Harari and is at once torn as to where she should

place her affection. Meanwhile Jerome issues a threat to Commander Osembenga - his

troops will fight him.

Jerome continues his diatribe against the evils of Commander Osembenga, stating that they

are only rebels because they do not respect the official rule of law, which has shown itself to

be brutal and have no regard for mercy. Mama drinks to the truth of this. Christian

hesitantly does the same.

12

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

Mr Harari introduces himself to Jerome and buys the rebel leader a drink. Mama encourages

the rebel men to stay and enjoy the evening, but the men leave, with action in mind. There

is a huge sense of relief at their departure. Christian does a crude impression of Jerome, and

the girls laugh, Sophie playing along. Unseen, Commander Osembenga enters with Laurent,

a sullen soldier. Abruptly Christian stops. The Commander asks about the truck he just saw

leaving the bar as he arrived. Christian tells a lie about an aid worker. The Commander is

unconvinced and remarks on the vehicle - expensive-looking.

Mama enters and greets the Commander nervously,

anxiously glancing at the door. There would be

trouble if the rebel leader returned. The

Commander settles down for a drink,

complimenting Mama. She asks him about any

trouble with Jerome Kisembe. The Commander

dismisses this ‘trouble’ - he states he is close to

shutting down Kisembe’s rebel militia, they are

chasing him down. The Commander accuses

Kisembe’s men of committing atrocities at the local

hospital, even removing one man’s heart: they force his hand to retaliate with force. Sophie

brings them drinks but cringes visibly at the thought of this violent man. The Commander

calls her back over, but Sophie tries to pry herself loose. Christian moves to assist but the

Commander persists with Sophie on his lap, struggling to get free. Mama takes notice,

calling Sophie away but the Commander pulls her back. A struggle ensues as Sophie pushes

him away. Mama promises him other women, but he insists on Sophie. Sophie spits at his

feet and declares ‘I am dead.’ Mama is horrified and the Commander is furious. Mama tries

to placate the situation to no avail and the Commander relents - if Mama will accompany

him outside. She knows what this means and acquiesces.

Mama re-enters, and slaps Sophie hard across the face, ordering to go out to the

Commander and give him some pleasure. Christian is shocked but Mama knows how

dangerous the situation is - offending the Commander is no light matter and is damaging to

her business. Christian balks at her use of the word ‘business’. Mama is indignant, criticising

his hypocrisy: he is happy to drink there, and now he questions her morals. She tells of her

struggle to survive, to build a business from nothing: she was not always Mama NadI, but

had to find her. Christian makes to leave. She warns that he’ll be back when he wants

another beer. Christian disagrees: he won’t be back.

SCENE FIVE

The Commander and Laurent stumble, laughing, out of the bar. The meet Fortune, who tells

them he has seen Jerome Kisembe inside Mama NadI’s bar, that she was hiding him today.

The Commander is incensed. Fortune tells him that Mama is also hiding his wife. The

Commander and Laurent exit quickly, in pursuit of Jerome Kisembe.

13

PLAY SYNOPSIS con’t

SCENE SIX

Dawn at the bar. Mr Harari paces, ready to leave and awaiting a lift out of the area with an

aid worker. Mama wipes down a bar and offers him a drink whilst he waits, which he

accepts. He is very anxious to leave this war-torn area. He talks about the nature of the war

and the difficulty in having to befriend both everybody and nobody at the same time. Mama

brushes it away - let the soldiers fight it out, is her attitude, because nothing will change in

the end - the fighting is futile. Mr Harari expresses his concern for girls like Sophie and

makes to leave. Mama stops him quickly, and asks him to sell the diamond: he will take

Sophie with him and give her the money from the diamond. He does not entirely understand

why but agrees. Mama calls Sophie, but before she can appear, Mr Harari has left in the car,

taking the rough diamond with him. Fortune enters with Commander Osembenga and

soldiers. He stands over Mama and accuses her of hiding Jerome Kisembe. She denies all

knowledge, calling Fortune crazy. Once again the Commander challenges her to reveal

Kisembe’s whereabouts but again she denies all knowledge. She offers the Commander a

drink but he refuses. The soldiers raid the bar, finding Mama’s lock box. They break it open

and take all the money. They throw Sophie, Mama and Josephine onto the floor - they will

only stop if Mama tells his where Kisembe is hiding. Josephine lets out that he was here.

Just then, Salima enters, a pool of blood forming in the middle of her dress; blood drips

down her legs. She screams at the soldiers. They stop abruptly, shocked. Fortune sees Salima

and rushes towards her. Mama calls urgently for some hot water to help Salima, trying to

keep her alive. Salima dies.

SCENE SEVEN

Some time later, in the bar. Sophie sweeps the floor,

singing. Mama stands at the door, trying to attract

business. It does not come. She despairs at the state of

business now, times are hard.

Christian enters in a new suit. Mama pretends not to be

pleased to see him, concealing her excitement. They greet

each other sarcastically, but not without affection.

Christian has managed to bribe his way past the road

block and is surprised to find Mama is still here. Mama

brushes this away, instead criticising Christian’s dress. He

flirts with her.

Sophie enters and hugs her uncle. He has brought her a

book and a letter from her mother, though he tells her

not to expect too much from the latter. Sophie is shocked

to receive a letter at all, and exits to read it alone.

Mama expresses her surprise at seeing Christian again, after their last encounter. He fights

with himself, but believes they have unfinished business. He once again asks Mama to settle

down with him. Again she refuses and tries to change the subject, but he persists, hard.

Finally she admits: she is ruined. Christian absorbs her words but does not leave. He

comforts Mama in his arms and will not let her push him away. He kisses her. Finally, they

dance together, Sophie and Josephine watching on.

14

CAST AND CREATIVE TEAM

Mama Nadi Yanna McIntosh

Christian Sterling Jarvis

Harari Richard Alan Campbell

Osembenga

Josephine

Simon

Laurent

Sofie

Fortune

Kisembe

Salima

Musician

Playwright

Director

Stage Manager

Production Manager

Set Design

Costume Design

Lighting Design

Sound Design

Property Master

Poster Design

15

Lucky Ejim

Abena Malika

Muoi Nene

Anthony Palmer

Sabryn Rock

Marc Senior

Andre Sills

Sophia Walker

Daniso Ndhlovu

Lynn Nottage

Philip Akin

Michael Sinclair

Doug Morum

Gillian Gallow

Nadine Grant

Rebecca Picherak

Chris Stanton

David Hoekstra

Art Group 22/Geffen

Playhouse

ABOUT OBSIDIAN THEATRE

Obsidian is Canada’s leading culturally diverse theatre company. Their threefold mission is

to produce plays, to develop playwrights and to train emerging theatre professionals.

Obsidian is passionately dedicated to the exploration, development, and production of the

Black voice. Obsidian produces plays from a world-wide canon focusing primarily, but not

exclusively, on the works of highly acclaimed Black playwrights. Obsidian provides artistic

support, promoting the development of work by Black theatre makers and offering training

opportunities through mentoring and apprenticeship programs for emerging Black Artists.

ABOUT NIGHTWOOD THEATRE

As Canada’s national women’s theatre since 1979, Nightwood has launched the careers of

countless leading theatre artists in the country. We have won Canada’s highest literary and

performing arts awards and more than ever our success proves the need for theatre that

gives voice to women and celebrates the diversity of Canadian society. We remain actively

engaged in mentoring young women and promoting women’s place on the local, national

and international stage.

ABOUT LYNN NOTTAGE

Lynn Nottage was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1964. Her parents were a schoolteacher

and a child psychologist. Keen on theatre from an early age, she attended New York’s High

School of Music and Art, before Brown University and Yale School of Drama. Her work often

deals with the lives of African Americans and the struggles of women.

Apart from Ruined, Intimate Apparel is probably Nottage’s best known play, centred on the

story of an African-American woman’s journey to independence, with her moving to New

York to pursue her dreams and becoming a seamstress. Fabulation, or the Re-Education of

Undine could be seen as a thematic sequel to this, and once again involves an AfricanAmerican woman dealing with change in New York. Undine is a successful publicist living in

Manhattan until her husband leaves her taking all her money. She is forced to return to

Brooklyn, to her former existence, and to deal with her working-class relatives.

Nottage was awarded the Guggenheim Grant for Playwriting in 2005. In 2007 Nottage won

the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant and the National Black Theatre Festival’s August

Wilson Playwriting Award. Ruined itself won several high-profile awards including an Obie

for Best New American Play in 2008, the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2009 and most recently,

co-winner of the newly established Horton Foote Prizes, awarded on August 30/10 named in

honour of the late legendary writer. Lynn Nottage is a visiting lecturer at Yale School of

Drama and sits on The Dramatists Guild Council, an alumna of new American dramatists.

Selected Plays

1993 Poof

1995 Crumbs from the Table of Joy

1998 Mud, River, Stone

1998 Por'Knockers

2002 Las Meninas

2003 Intimate Apparel

2004 Fabulation, or the Re-Education of Undine

2007 Ruined

16

LYNN NOTTAGE ON RUINED

Lynn Nottage writes here about the journey she went on in search of Ruined.

Six years ago, I travelled to East Africa to interview Congolese women fleeing the armed

conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. I was fuelled by my desire to tell the story of

war, but through the eyes of women, who as we know rarely start conflicts, but inevitably

find themselves right smack in the middle of them. I was interested in giving voice and

audience to African women living in the shadows of war.

The circumstances in the DRC are complicated; there is a slow simmering armed conflict that

continues to be fought on several fronts, even though the war officially ended in 2002. You

have one war being fought for natural resources between militias funded by the government

and industry, you have the remnants of an ethnic war, which is the residue of the genocide

in Rwanda that spilled over the border into Congo, and then you have the war that I examine

in my play Ruined, which is the war being waged against women. To throw some statistics at

you, according to International Rescue Committee, nearly 5.4 million people have died in

that country since that conflict began; every month, 45,000 Congolese people die from

hunger, preventable disease and violence related to war. The fact is the war in Congo is the

deadliest conflict since World War II. It is sometimes called World War III, because of the

international interests that fuel the conflict in order to exploit the land, which is rich in

minerals such as gold, coltan, copper and diamonds.

In 2004 I went to East Africa to collect the narratives of Congolese women, because I knew

their stories weren’t being heard. I had no idea what play I would find in that war-torn

landscape, but I travelled to the region, because I wanted to paint a three dimensional

portrait of the women caught in the middle of armed conflicts; I wanted to understand who

they were beyond their status as victims.

I was surprised by the number of women who readily wanted to share their stories. One by

one, through tears and in voices just above a whisper, they recounted raw, revealing stories

of sexual abuse and torture at the hands of both rebel soldiers and government militias. The

word rape was a painful refrain, repeated so often it made me physically sick. By the end of

the interviews I realised that a war was being fought over the bodies of women. Rape was

being used as a weapon to punish and destroy communities. In listening to their narratives I

came to terms with the extent to which their bodies had become battlefields.

I remember the strong visceral response that I had to the very first Congolese woman who

shared her story. Her name was Salima, and she related her story in such graphic detail that I

remember wanting to cry out for her to stop, but I knew that she had a need to be heard.

She’d walked miles from her refugee camp to share her story with a willing listener. Salima

described being dragged from her home, arrested and wrongfully imprisoned by men

seeking to arrest her husband. In prison she was beaten and raped by five soldiers. She

finally bribed her way out of prison, only to discover that her husband and two of her four

children were abducted. At the time of the interview she still had not learned the

whereabouts of her husband and two children. I found my play Ruined in the painful

narratives of Salima and the other Congolese women, in their gentle cadences and the

17

LYNN NOTTAGE ON RUINED con’t

monumental space between their gasps and sighs. I also found my play in the way they

occasionally accessed their smiles, as if glimpsing beyond their wounds into the future.

In Ruined Mama Nadi gives three young woman refuge and an unsavoury means of survival.

As such, the women do a fragile dance between hope and disillusionment in an attempt to

navigate life on the edge of an unforgiving conflict. My play is not about victims, but

survivors. Ruined is also the story of the Congo. A country blessed with an abundance of

natural beauty and resources, which has been its blessing and its curse.

Lynn Nottage, April 2010.

18

INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP AKIN

Why did you decide to direct Ruined?

I love Lynn Nottage’s plays. From the first time I

heard about Ruined I was intrigued by what she

would do with it and so I followed the

development of play and finally saw it in New

York. I was so taken with the fact that it was an

African story. One that was not told via a

Western character and that it speaks with hope.

The characters and their stories spoke to me in

a profound way and I just knew that I needed to

bring this play to Toronto

What attracts you to the Berkeley Theatre?

What appeals to you about the space?

The Downstairs space at the Berkeley has both a breadth of space and an intimacy that will

allow the play to sit deep in the audience. It allows one to wrap the action around the

audience and pull them in.

Why do you think Ruined is relevant to audiences now?

Ruined is relevant now because it lives in the ongoing now. The survivors in this play are

based on real survivors. Their stories are continuing to this day and in fact new stories of war

and its devastation of women continue to be written even as you read this. But it is also

relevant because it shows people who continue with their lives. People who can find hope

and friendship even in the most horrific of circumstances.

What research do you do before rehearsals start?

I have done more research on this play than on any other that I have been involved in. Part

of it is online at http://ruined-obsidian.blogspot.com/. Of course I have read as much about

the ongoing war, mining issues, music, dance, road conditions and accents etc. All help to

frame the stakes for each character and give a rich texture to every word. It is also

imperative that to keep in mind that while the research leads to some pretty dark places

that darkness needs to have light to fully exist.

How did you go about understanding what life is like for women in the play?

By listening. It’s funny because when I talked to Lynn after seeing the NY production I asked

her why it wasn’t as bleak as I had expected. She said, “Because it was directed by a

woman.” I figured that there was a lot of merit in why she said that and so I have tried to

listen and fully understand how those differing sensibilities could manifest themselves.

None of the characters is entirely virtuous or malicious. Why do you think that is?

Kate Whoriskey who directed the premier production wrote the introduction to the

published version of the play. She speaks of a conversation that Lynn had with a survivor of

the Rwandan genocide and asked him about life after the genocide. He said, “We must fight

to sustain the complexity.” That phrase became the guiding spirit to their production and I

have taken it on for this one. Thus no one is entirely one thing or the other and that makes

them universally human. It is that complexity of character that Lynn creates so well and

19

INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP AKIN con’t

thereby brings to life people we can understand and relate to. Without that deep human

involvement what we would get are ciphers or mouthpieces for propaganda. Instead we

have people we are viscerally affected by.

How is directing a new play different to working on other, older texts?

I have never worked on older texts where the playwright is not alive so this is really what I

am used to. I like having that direct connection with the playwright and have built several

long lasting friendships because we work together to reveal the playwright’s message.

What does this play mean to you personally? What’s your inspiration?

It was in 2008 that I first heard of this play and I have been working to produce it ever since.

Ruined is a necessity for me. Well perhaps more of an obsession really. This story has hit me

deep inside and no matter what I needed to bring this play to the stage.

This is a play of survivors. Not victims. And that is an African story that you do not see very

often. The women in this play are the distillation of many women who have survived horrors

we can only imagine and yet they are still wrapped in humanity. How could I not want these

people to live here for our audience?

20

DRC: THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

The Democratic Republic of Congo is a vast country in central Africa, one rich in economic

resources; and yet the country is one of the worlds poorest, with a long history of rife

corruption and civil war.

The first European known to have visited the region was Portuguese navigator Diogo Cao in

1482 who established ties with the then King of Kongo. During the 16th and 17th centuries,

British, Dutch, Portuguese and French merchants engaged in the slave trade. In 1884

European powers recognised King Leopold II’s claim and he announced himself

head of the ‘Congo Free State’. King Leopold expanded and consolidated his control and

exploitation of the region at the cost of millions of deaths of Congolese people.

Known as Zaire until 1997, the DRC has faced constant civil unrest, with government

corruption widespread and militia groups forming and fragmenting and re-forming almost

constantly over the last century. The region is made up of several peoples, notably the Hutus

and Tutsis. As the power structures oscillated between the various interest groups, often

reinforced by the control or influence of residual colonial powers, so communities of exiled

and refugee populations were established throughout the region, many of whom formed

armed groups and rebel factions within and across country borders. Other countries in the

region and further afield also fuelled conflict through the profitable arms trade and the

exploitation and control of the region’s rich mineral deposits. The country was a Belgian

colony until 1960, whereupon independence brought the country immediately into an army

mutiny and a bold attempt at secession by the province of Katanga, an area hugely rich in

natural mineral wealth. In 1961, the then prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, was seized and

killed by troops loyal to army chief Joseph Mobutu. Mobutu himself seized power in 1965,

when he renamed the country Zaire and himself Mobutu Sese Seko. He turned the country

into a centre for campaigns against the Soviet-backed Angola and in doing so guaranteed US

backing. But he simultaneously made Zaire synonymous with corruption.

Following the Cold War, the US lost interest in Zaire and the country’s internal corruption

intensified. In 1997 neighbouring Rwanda invaded the country to flush out extremist Hutu

militias. This gave a sharp boost to the anti-Mobutu rebels, who quickly captured the capital,

Kinshasa, overthrew Mobutu’s government, installing Laurent Kabila as president and

renaming the country the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Despite the new government, political unrest continued apace. A new rebellion was

provoked by a surging rift between Mr Kabila and his former allies, the latter backed by

Rwanda and Uganda. Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe in turn took Kabila's side, and the

whole country effectively became a battleground of continental proportions. This conflict,

known as the Second Congo War, raged between 1998 and 2003, and has been termed

Africa’s world war. The five-year war pitted government forces, supported by Angola,

Namibia and Zimbabwe, against rebel militia backed by Uganda and Rwanda. The war was

one of the worst emergencies in Africa in recent decades and claimed approximately three

million lives, in a combination of war violence or its by-products of disease and malnutrition.

Despite a peace deal and the formation of a transitional government in 2003, civil unrest has

never entirely ceased. In 2008 an escalation of coup attempts and localised violence caused

21

DRC: THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO con’t

renewed fighting in the eastern part of the country. Thousands of civilians were displaced

when Rwandan Hutu militias clashed with government forces. Another rebel militia group

led by General Laurent Nkunda had signed a peace deal with the government, but clashes

broke out just months later. Gen Nkunda's forces advanced the provincial capital Goma in

the autumn, attacking government bases and causing civilians and troops to flee. UN

peacekeepers desperately tried to hold the line alongside the remaining government forces.

In January 2009 the government attempted to bring the situation under control by inviting in

troops from neighbouring Rwanda to engage in a joint campaign against the rebel Hutu

militias active in the east of the DRC. General Nkunda was arrested by Rwanda, who had

until then seen him as a key ally. At present eastern areas remain beset by widespread

localised violence. This unending conflict may be in no small part due to the war’s economic

as well as political motivations. The country’s vast mineral wealth is often at the centre of

points of conflict, fuelling fighting by rival factions and splinter militia groups taking

advantage of the continuing anarchy to make personal gain. The West’s persistent reliance

on technology manufacture demanding the Congo’s mineral ores brings a sustained fan to

the fire of a war turned in on itself.

CONGO FACTFILE

Full name: Democratic Republic of the Congo

Population: 66 million (UN, 2009)

Capital: Kinshasa

Area: 2.34 million sq km (905,354 sq miles)

Major languages: French, Lingala, Kiswahili, Kikongo, Tshiluba

Major religions: Christianity, Islam

Life expectancy: 46 years (men), 49 years (women) (UN)

Monetary unit: 1 Congolese franc = 100 centimes

Main exports: Diamonds, copper, coffee, cobalt, crude oil

GNI per capita: US $150 (World Bank, 2008)

22

WOMEN AND THE CONFLICT

Article from Amnesty International

We have been campaigning to Stop Violence Against Women against the legal background of

the UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. One of our

concerns has been the impact of conflict on women – most commonly reported as rape,

though war and conflict affect women in many different ways. Ruined is about the

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) but the effects of conflict on women are similar

everywhere, be it in Northern Ireland, Israel/Occupied Territories, Balkans or Afghanistan.

During and after a conflict, civilians try to go about their normal daily lives – feeding their

family, earning a living, seeking education, keeping healthy and maintaining a semblance of

dignity and family life. All civilians, men, women and children, face great hurdles in trying to

keep things together. But the particular challenges faced by women are often poorly

understood. In peace negotiations and reconstruction efforts, the policies, solutions and

resources proposed often fail to target the root problems and traditionally focus on men,

the returning soldiers. Women are usually completely absent from the decision-making

process and their needs, and the key role they can play, are not highlighted in reconstruction

programmes. UN Security Council Resolution 1325, passed in 2000, is very clear that we

cannot expect to achieve a lasting, sustainable peace and economic regeneration unless the

whole society, including the at least 50% who are women, are able to play a full economic

and political role in designing, delivering and implementing the peace. However, these are

fine words which often fall short in practice. A recent example was in Liberia, where there

were many women ex-combatants. Some had chosen to join armed groups, others were

abducted; almost all suffered mass rape, were often forced to act as ‘army wives’ and bore

many children. In the first attempted peace initiatives, the UN programme of disarmament

and re-integration, conceived by men, failed to factor in the experiences of these women excombatants. Some well-intentioned reintegration initiatives offered access to education and

training, and to small funds to start income-generating schemes. To benefit from these

schemes, ex-combatants had to come forward, hand in their weapon and declare

themselves ex-combatants. In many cases, however, the women had either not been given

weapons or male commanders had taken them away. As a result it was almost exclusively

men who benefited from the programmes. The training and education schemes, with no

childcare, were set up in locations and at times making it difficult or unsafe for women to

attend. Women were deterred from declaring themselves ex-combatants as they faced

being stigmatised and ostracised in their communities – either because they might have

committed violent acts, or because they had been raped. The UN initiatives did not take

account of the reality and severity of stigma against such women, or offer any measures to

tackle it.

Encouragingly, many local women are taking the initiative and developing schemes to help

women rebuild their lives and those of their children, to the advantage of the local

community and economy. The most successful of these precisely address the need to create

safe women-only spaces to tackle stigma. They also always include income-generating

schemes to give women some independence, as they are often rejected by the men on

whom they have traditionally depended.

Such schemes not only benefit the women themselves but also strengthen the long-term

23

WOMEN AND THE CONFLICT con’t

economic stability of their communities. Their income generation is usually reinvested in

local businesses and their community, which raises the general standard of living, creates

employment and stimulates trade and stability. According to the World Bank Gender Action

Plan: ‘A host of studies suggest that putting earnings in women’s hands is the intelligent

thing to do to speed up development and the process of overcoming poverty. Women

usually reinvest a much higher portion in their families and communities than men,

spreading wealth beyond themselves. This could be one reason why countries with greater

gender equality tend to have lower poverty rates.’

NUMBERS: IN THE KIVU PROVINCES

About 1600 women are raped every week, mainly by armed men.

More than 8000 cases of rape were reported in 2009.

At least 1,350,000 people are displaced; around 1,000,000 of these were displaced in 2009.

Source: UN Office of Humanitarian Affairs, 9 February 2010

24

RAPE: A WEAPON OF WAR

Heather Harvey, a Stop Violence Against Women campaigner from Amnesty International

speaks of Rape: A Weapon of War

There is a tendency to assume that rape is a natural fallout of war, or a few bad apples

running wild. In fact, during wars, attacks on civilians have always been termed War Crimes

but it was never taken that seriously. The use of rape as a systematic tactic of warfare

though only began to be really widely recognised in the Balkans conflict.

The Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Tribunal of (the former) Yugoslavia

1998 was unusual in being drafted with input of women’s groups following that conflict. As a

result it included the most extensive definition of rape of any country, even today. The ICT of

Rwanda and Yugoslavia have reaffirmed that rape – even just one rape – is a war crime, but

that rape on a mass and widespread scale as a tactic or weapon of war is a crime against

humanity and can be a constitutive element of genocide.

‘Rape as a weapon of war’ refers to the deliberate, strategic and widespread use of rape as a

tactic to achieve military goals. The aim of war is generally to gain control of a territory and

its resources. To do this you have to exterminate, subjugate, win over or cause to flee the

enemy or target population; you also aim to minimise the cost, outlay and loss of your own

soldiers’ lives, and ensure that the enemy is not able to regroup or form any viable

opposition or resistance. Rape is a cheap and easy means to achieve this. It requires no

major financial outlay, weapons, ammunition, or transport systems. It spreads terror and

causes populations to flee the land you want to take over. It is so utterly destructive that

people cannot look each other in the eyes let alone form a working resistance. In many cases

the rapes take place in front of family and community, men and boys may be forced to rape

their own relatives. And of course men and boys themselves may be raped. Mass rape is not

a ‘fair’ way to fight: this is precisely why it is prohibited in the laws of war.

The problem is that as long as mass rape as a strategy goes unchallenged it will continue to

be a preferred weapon or tactic. Women who are victims of rape in conflict will often be

pregnant from the rape with little or no access to choices or services on how to deal with

this. There are of course severe risks of sexually transmitted diseases including HIV aids.

Many of the women will be subjected to horrific injuries and mutilations. In many cases they

will have severe long-term internal vaginal and anal injuries. These are often life-threatening

but can also result in problems in childbirth and fertility for the future and can often result in

severe tearing and laceration that can cause haemorrhaging, fistula and severe infections.

Women who bear such disabling illnesses and injuries or who have been victims of rape,

particularly in the context of the DRC, are ‘ruined’. They will be rejected and ostracised by

their husband, family and community. This will mean that in societies where few women

have been given access to education or to the labour market and where a woman’s status

and access to income is dependent on her role as a wife and mother then she will also be

unmarriageable, undesirable and destitute having to turn to anything at all as a survival

strategy.

25

RAPE: A WEAPON OF WAR con’t

War crimes have been committed by all those involved in fighting in the DRC. The UN has

also clearly identified that if you do not prosecute and provide redress for war crimes such

as rape and other human rights violations committed in a conflict then the conflict will be

reignited, prolonged and deepened (UN resolution 1820). Amnesty is calling for better

implementation of both Resolution 1325 involving women in post conflict decision making

and Resolution 1820 challenging impunity for war crimes notably rape in conflict.

Amnesty International welcomes this brave play as an illustration of many of the horrors of

the conflict in DRC and conflicts around the world. We hope you will join us in our struggle

for human rights.

26

CONFLICT MINERALS IN THE DRC

Sexual violence in Congo is often fuelled by militias and armies warring over “conflict

minerals,” the ores that produce tin, tungsten, and tantalum – the ‘3 Ts’ – as well as gold.

Armed groups from Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda finance themselves through the illicit

conflict mineral trade and fight over control of mines and taxation points inside Congo. The

story does not end there. Internal and international business interests move these conflict

minerals from Central Africa around the world to countries in East Asia, where they are

processed into valuable metals, and then onward into a wide range of electronics products.

Consumers in the United States, Europe, and Asia are the ultimate end-users of these

conflict minerals, as we inadvertently fuel the war through our purchases of these

electronics products. This trail has been well documented by the United Nations and others.

The principal conflict minerals are:

TIN (produced from cassiterite)

Used inside your mobile phone and all electronic products as a solder on circuit boards. The

biggest use of tin worldwide is in electronic products. Congolese armed groups earn

approximately $85 million per year from trade in tin.

TANTALUM (produced from coltan)

Used to store electricity in capacitors in iPods, digital cameras, and mobile phones. 65 to 80

percent of the world’s tantalum is used in electronic products. Congolese armed groups earn

an estimated $8 million per year from trading in tantalum.

TUNGSTEN (produced from wolframite)

Used to make your mobile phone or Blackberry vibrate. Tungsten is a growing source of

income for armed groups in Congo, with armed groups currently earning approximately $2

million annually.

GOLD

Used in jewellery and as a component in electronics. Extremely valuable and easy to

smuggle, Congolese armed groups are earning between $44 million to $88 million per year

from gold.

27

ITURI CONFLICT

Ruined is set in the Ituri region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. This page outlines the

specific conflict that has plagued the North Eastern part of the country.

The official dates of the conflict are 1999-2003, however there was ‘low-level’ violence,

requiring an EU peace keeping force until 2008.The conflict in the North Eastern Region is

between the agriculturist Lendu tribe and the pastoralist Hema tribe. The Nationalist and

Inegrationalist Front (FNI) represent the Lendu and the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC)

fight for the Hema. Increased violence as a result of ‘borrowing’ ethnic ideology from the

Hutu-Tutsi conflict. Human Rights Watch reported that the Lendu began thinking of

themselves as kin to the Hutu, whilst the Hema began to identify themselves with the Tutsi.

Background: The Belgain colonists favoured the Hema, resulting in them being wealthier and

better educated than the Lendu. This divergence continued into modern times. However,

the two peoples have largely lived together peacefully, practicing extensive intermarriage.

Northen Hema people speak Lendu, southern Hema people speak Hema.

Longstanding grievances about land issues erupted on at least 3 previous occasions 1972,

1985, 1996. A lot of the animosity revolves around the 1973 ‘land use law’, which allows

people to buy land which they do not inhabit and then force residents to leave two years

later when ownership can no longer be legally contested. Some Hema were allegedly using

this tactic in 1999. The 1994 Rwandan genocide made people even more aware of their

tribal and lingustic affiliation. Influx of Hutu refugees into the region, which led to the 1st

Congo war served as further emphasis. However, when the 2nd Congo War began in 1998,

the situation between the Hema and Lendu tribes reached the level of regional conflict. The

area was occupied by the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) and the Ugandan backed

Kinsangani faction of the rebel Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD-K) under the leadership

of Ernest Wamba dia Wamba.

The Ituri province was created out of the eastern Orientale province in June 1999 by James

Kazini, commander of the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF). He ignored the protests of

the Rcd-K leadership and appointed a Hema to be the new governor. This convinced the

Lendu that Uganda and the RCD-K backed the Hema over them and violence erupted

between the 2 groups. Reports indicate that Lendu trainees refused to join the RCD-K and

instead set up ethnically-based militias. Fighting began to slow in late 1999 when the RCD-K

named a neutral replacement to head the provincial government. However in 2001, it flared

up again after the UPDF replaced the government with a Hema appointee. The RCD-K

appointee was moved to Kampala and held by the Ugandan government without

explanation. Wamba dia Wamba’s (RCD-K) military base collapsed shortly after as it was now

without Ugandan support, largely because it was perceived to have a pro Lendu stance.

Although the official conflict ended in 2003, the low level conflict that continued has killed

tens of thousands more people. The continued Ituri conflict has been blamed both on the

lack of any real authority in the region, which has become a patchwork of areas clamed by

armed militia, and the competition among various armed groups for the control of natural

resources in the area. 50% of militia members are under 18 and some are as young as 8.

28

PLACES IN RUINED

A guide to some of the key places mentioned in Ruined.

BUNIA

Bunia is a city in Democratic Republic of the Congo and is the capital of Ituri Province. The

city was formerly the headquarters of Ituri district when it was part of the former Orientale

Province. As of 2009 it had an estimated population of 106,197. Bunia lies at an elevation of

1275m on a plateau about 30 km west of Lake Albert in the Great Rift Valley, and about 25

km east of the Ituri Forest. The city is at the center of the Ituri conflict between the Lendu

and Hema. In the Second Congo War the city was the scene of much fighting and many

civilian deaths were incurred. Consequently the city is the base of one of the largest United

Nations peacekeeping forces in Africa, and its headquarters in northeastern DRC. There are

White Christian Missions in Bunia and have been since the Belgians occupied DRC.

The main dirt highways connecting north-eastern DR Congo with Kisangani to the west and

Butembo and Goma to the south pass through Bunia, but have fallen into disrepair and are

virtually impassable, especially after the frequent rains. Bunia is only 40km from the

Ugandan border running down Lake Albert, but there are no road connections across the

Great Rift Valley to the closest Ugandan towns of Toro and Fort Portal. Instead a dirt

highway going north-east reaches Arua and Gulu north of the lake. Before the war made the

route impassable, this was the chief trade route between the DRC and Uganda, as well

between the DRC and Juba in Sudan, and Bunia was an important market city, for crossborder trade as well as internal trade. Bunia is linked to the small port of Kisenye on Lake

Albert by a 60-kilometre dirt track via Bogoro, which has a spectacular and dangerous 600metre descent of the western escarpment of the Great Rift Valley. Kisenye has a jetty from

which boat transport can link with Mahagi-Port at the north end of the lake, and with

Butiaba on the Ugandan side and Pakwach on the Albert Nile.

CHINA

From the DRC, coltan is exported to facilities, such as Ningxia Non-ferrous Metals Smeltery

in China, for processing and is manufactured into consumer and industrial goods sold in

North America and Europe.

ITURI RAINFOREST

The Ituri Rainforest is about 63,000 km square in area, and is located between 0° and 3°N

and 27° and 30° E. Elevation in the Ituri ranges from about 700 m to 1000 m. The average

temperature is 31°C and the average humidity is about 85%. The Ituri forest is the home of

the Mbuti pygmies, one of the hunter-gatherer peoples living in equatorial rainforests

characterised by their short height (below one and a half metres, or 59 inches, on average).

KISANGANI

Population in 2004 was 682,599, 447 m above sea level, 696 km from Bunia and 2912 km

from Kinshasa. The city's land area is estimated at 1910 square kilometres. The City of

Kisangani has a density of 229 inhabitants per square kilometre. The language most spoken

at home by the population in the city is Swahili and Lingala, followed by French. The official

language of Kisangani is French as defined by the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of

the Congo. Kisangani is the 3rd largest city in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the

29

PLACES IN RUINED con’t

largest of cites that lie in the tropical woodlands of the Congo. It is the provincial capital of

Tshopo. Formerly known as Stanleyville in French, the city takes its present name from

Boyoma, the seven-arched falls located north of the city, whose name was also initially given

to the landscape on which the city is located. Kisangani is the Swahili name of the city, whilst

in Lingala it is called Singitini (or Singatini), each of which share the same meaning of ‘the

City on the Island’. Kisangani is the nation’s major inland port after Kinshasa, an important

commercial hub point for river and land transportation and a major marketing and

distribution centre for the north-eastern part of the country. It has been the commercial

capital of the northern Congo since the late 1800s. Kisangani has been home to influential

politicians, including the national hero Patrice Emery Lumumba, the first prime minister of

the country. Before the country gained independence from Belgium in 1960, Kisangani was

reputed to have more Rolls-Royces per capita than any other city in the world. In 1999 the

city was the site of the first open fighting between Ugandan and Rwandan forces in the

Second Congo War. This followed the fracturing of the anti-government rebel Rally for

Congolese Democracy (RCD) into camps based in Kisangani and Goma. The fighting was also

over the gold mines located near the town. The local population were caught in the crossfire

between Ugandan and Rwandan military forces which led to the destruction of about a

quarter of the city and some 3000 fatalities.

LEBANON

Mr Harari is a Lebanese diamond merchant. Beirut is 2,256 miles North East of Bunia.

MBUTI

The Mbuti people have lived in the Ituri Forest for many thousands of years, and it is even

speculated that they might be the earliest inhabitants of Africa.

ORIENTALE PROVINCE

Orientale (formerly Haut-Zaïre, then Haut-Congo) is a province of the Democratic Republic of

Congo. It lies in the northeast of the country, and its provincial capital is Kisangani. It borders

Equateur province to the west, Kasai-Oriental to the southwest, Maniema to the south, and

Nord-Kivu to the southeast. It also borders the Central African Republic and Sudan to the

north, and Uganda to the east. The Ituri district of Orientale was the scene of Ituri conflict.

The Ituri province was created out of the eastern Orientale province in June 1999 by James

Kazini, commander of the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF).

UGANDA

Christian imports cigarettes from over the border in Uganda. Uganda boarders the Ituri

region of the DRC. The Ugandan People’s defence force created 4 provinces out of the

Orientale region in 1999, including the Ituri. The Ugandan’s backed a Hema to become

leader of the Ituri province twice, in 1999 and in 2001. They also support pro Hema militia.

YAKA YAKA MINE

The Yaka are an ethnic group of Southwestern Democratic Republic of the Congo and

Angola. They number about 300,000. They live in the forest and savanna areas between the

Kwango and Wamba rivers. They are very artistic. Many of their religious and cultural

customs transcend ethnic boundaries, and are shared with the Suku and Lunda.

30

PRACTICAL EXERCISE ONE

Exercise 1. There’s no blood on my mobile!

Duration: 25 mins

Aim: To understand the context of the play, particularly in relation to the mining of coltan

and the impact that this has on those living in the DRC

Practical Work: Read through the context articles. An article in The Independent in May 2006

said: ‘Men, women and children – lots of children – pick desperately with makeshift

hammers or their bare hands at the red earth, hoping to find some coltan or casserite to set

on the long conveyor belt to your house, or mine.’ Brainstorm the supply chain, or ‘conveyor

belt’, of coltan – how does it reach the consumer and what are the consequences of mobile

phone consumerism in the West? Now think about this physically. Create six, eightbeat

phrases – three relating to the use of coltan and three highlighting its impact in the DRC.

Now try playing these all together – a literal conveyer belt from the mines to the consumer.

Evaluate: Ask the students to consider who should take responsibility for the situation in the

DRC. Is it the consumer who willingly upgrades his or her mobile phone and consequently

fuels the demand for more coltan? Is it the mobile phone companies who all have Corporate

Social Responsibility Policies, yet claim that they do not know the origin of the minerals used

in their products? Or is it the rebel groups in the DRC using coltan to fund weapons? Or is it

the corrupt Congolese government and its army, with its horrific human rights record? Ask

volunteer students to represent each level in the supply chain, from the miners in the DRC

through to the consumers in the West and have them arrange themselves first in order of

supply/demand and then in order of overall responsibility.

PRACTICAL EXERCISE TWO

Exercise 2. Playing with Status

Duration: 30 mins

Aim: To explore hierarchy in the everyday lives of people in the DRC – particularly the

women.

You will need: Multiple copies of Script Extract #1

Practical Work: To warm into this exercise, have students silently order themselves in a line

by age, height, colour of hair, birth date etc. What gives a person status? Is it positions of

authority or are their other factors? Have students read the following scene between Mama

Nadi and the Commander – how does the status play out between them? Try playing the

scene on a line with the actors taking a step forwards or backwards on every line, depending

on their status. This is a very visual way of seeing how status shifts.

Evaluate: Ask the group how they felt playing the scene on a line? Was it clear who gained

status and when? Was it always obvious who had the higher status? What does this exercise

say about the role of women in the DRC? Using this analysis, it might be worth replaying the

scene using the original text.

31

PRACTICAL EXERCISE THREE

Exercise 3. Salima’s Story

Duration: 30 mins

Aim: To explore the horrific impact that the conflict in DRC has on women