European University Institute

Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

Mediterranean Programme

Seventh Mediterranean Social and Political Research Meeting

Florence – Montecatini Terme, 22–26 March 2006

After Van Gogh: Roots of Anti-Muslim Rage

Martin van Bruinessen

International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM) /

Utrecht University

Workshop 10

Public Debates about Islam in Europe: Why and How 'Immigrants' became 'Muslims'

Workshop supported by the

International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM)

Leiden, The Netherlands

© 2006. All rights reserved.

No part of this paper may be distributed, quoted or reproduced in any form without permission from

the author(s).

For authorised quotation(s) please acknowledge the Mediterranean Programme as follows:

“Paper presented at the Seventh Mediterranean Social and Political Research Meeting, Florence &

Montecatini Terme, 22–26 March 2006, organised by the Mediterranean Programme of the Robert

Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute.”

Abstract:

As in other West-European countries, public discourse on immigration in the

Netherlands — or at least that of politicians and columnists in the media — has

experienced a dramatic paradigm shift in which Islam has become increasingly

identified as the nexus of all that is wrong. A reframing took place in which all

immigration problems, petty crime, ‘black’ schools, honour-related violence, etcetera

came to be identified with Islam and perceived as parts of a package that also included

jihadist violence abroad and a few cases of jihad recruitment at home, and of course the

headscarf.

This paper argues that a civil religion or civil cult appears to be developing that fills the

gap left by the decline of the ‘pillar’ system. Islam has come to play a defining role in

the concept of the nation that is the object of this cult, and three recent martyrs (Fortuyn,

Hazes, Van Gogh) have provided the cult with emotion, meaning and coherence. These

saints succeeded in transcending class and (sub-)culture boundaries by liberating

common emotions. The discursive shift from class (‘guest workers’) or race (‘blacks’,

‘Turks’) to culture (‘Muslims’) as the defining characteristic of the Outsider made

xenophobia socially acceptable to segments of the middle classes that had resisted the

seductions of racism. This shift therefore made a broader coalition of worshippers of the

Dutch nation and Dutch culture possible, but it also turned the integration of Muslims

into Dutch society and Dutch culture into a formidable problem.

The polarising debates between columnists and politicians that have filled the media

during the last couple of years have had a significant impact on relations at the

grassroots level. Yet one should be cautious not to consider the leading discourse in the

media as a representative reflection of debates, opinions and attitudes in local

neighbourhoods. Focus groups discussions at local level indicate both the impact of

media discourse and the existence of de-escalating mechanisms and self-restraint.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 1 of 23

Three funerals

In the past few years the Netherlands witnessed three funerals of public personalities that

turned into massive outbursts of emotion and were accompanied by spontaneously invented

rituals that could not but strike the dry-eyed observer as religious. Populist politician Pim

Fortuyn, filmmaker and television personality Theo van Gogh and popular singer André

Hazes were killed by an animal rights activist, a young Moroccan Islamist and an excess of

alcohol, respectively, and the mass manifestations following their sudden deaths were very

much like forms of worship in a new civil religion.

Religion in the Netherlands had been associated with the pillar system: different religious

denominations existed beside one another without much contact at the grassroots or middle

levels; the integration of society took place at the top. The break-up of the pillar system in the

sixties and seventies of the last century, increased social mobility, and secularisation went

hand in hand. A form of civil religion as existed in the United States (Bellah 1970) never

developed in the Netherlands; the pillar system probably prevented this. Nor had the Dutch

state ever felt the need to develop the rituals of a state religion, as the authoritarian European

states of the 1930s developed and some states continued practising (Lane 1981). The

martyrdom of Pim, Theo and André — all three were, especially after their deaths, often

referred to by their first names only, suggesting intimacy, and occasionally observers spoke of

‘Saint Pim’, ‘Saint Theo’ and ‘Saint André’ — brought about spontaneous expressions of love

for and self-identification with a resurgent counter-culture that was felt to be more

authentically Dutch than the cultural and political elite that had dominated the eighties and

nineties: the ‘politically correct’ multiculturalists, the ‘left church’.

Hazes was an icon of Dutch popular culture, a crooner of sentimental songs in which a vast

audience recognised itself and its own uncontrolled emotions. He was recognised as ‘national’

in the way the Dutch national football team is national – in fact, one of his most popular songs

was an ode to the national team. His songs belonged to a type that was originally associated

with certain lower-class neighbourhoods of Amsterdam (in one of which he grew up and

worked as a bartender before becoming a well-known singer), but they found acceptance in

ever broader circles, and even part of the cultural elite came to adopt Hazes: a serious

filmmaker made a documentary about him that was shown in art houses; after his death, some

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 2 of 23

commentators dubbed him the father of ‘Nether-Blues’ – blues being a genre of music with a

certain cultural appeal, this represented an upward revaluation of Hazes’ cultural contribution.

His funeral, on 27 September 2004, brought out an emotional crowd of 50,000, filling the

country’s largest football stadium. The entire farewell ceremony was broadcast live on

television and seen by some 5 million viewers while another 3.1 million watched the event for

at least five minutes. Only the most important international football tournaments attract

similar numbers of viewers. Of the three funerals mentioned here, it was the one that most

resembled a royal funeral, a well-organised state ritual.1

Some observers commented on the similarity to Princess Diane’s funeral in 1997, considered

as the largest media event ever. Whereas Tony Blair anointed Diane as ‘the Princess of the

People,’ Hazes was a man of the people in an altogether more earthly sense, drinking,

sweating, loving, and singing about his simple but strong emotions, in which may could

recognize themselves. Like Diane’s, his personal life had been extremely public, and many

admirers may have felt they knew him better than they knew their own relatives. Several

analysts (Beunders 2002; de Hart 2005) have pointed at the publicness of private emotions

and the obsession of the modern media with emotion as central elements in contemporary

Dutch (or for that matter Western) culture. I should like to point at one difference between the

highly mediatised and tearful funerals of Diane and of Hazes: the latter was a distinctly Dutch

event, producing disgust in some of the more intellectual commentators but expressing a

sentimental identification with an authentic, white Dutchness.

Unlike the Fortuyn and Van Gogh funerals, Islam or the Muslim presence in the Netherlands

were never even hinted at in the reporting on Hazes’ last rites. But it was a very ‘white’ event.

Muslims and other immigrants were not excluded; they simply were not there. To my

knowledge, Hazes had never said anything in public on Islam or Muslims. But he was an icon

of authentic Dutch identity as imagined by folk nationalists.

Fortuyn and Van Gogh were to a much lesser extent ‘men of the people;’ both were

extravagantly deviant in their public behaviour and discourse. Fortuyn was, however, a

1

Many newspaper columnists commented on this, for the Netherlands unusual, event and some in fact related it

to a widespread sense of insecurity and search for identity. The only academic analyses I have seen are the thesis

(in cultural studies) by Blokland (2005), which usefully summarises most of the comments in the print media,

and the sociological study by de Hart (2005).

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 3 of 23

leading exponent of folk nationalism and pride in Dutch identity. He became enormously

popular when he began challenging and ridiculing the political elite of the then socialdemocrat and liberal government parties. A very effective debater, emotional, vain,

outrageous, funny, and eloquently speaking a language common people could understand, he

moved like a destructive hurricane over the political landscape. His most virulent and

successful attacks were on multiculturalism and the neglect of the problems of poor urban

neighbourhoods.

He combined effectively the anti-Muslim attitudes and discourses of two different social

strata: the lower class Dutch’s resentment of the presence of immigrants who were competing

with them for cheap work and housing and whom they saw as chiefly responsible for the rapid

deterioration of their built environment; and the elitist appeal to the values of the

Enlightenment that were perceived to be threatened by a backward, unenlightened Muslims.

More importantly, perhaps, was that he broke the mould of what was called ‘political

correctness’ and oblique language: one of the slogans that became associated with his style of

polemical politics was “I say what I think and I do what I say” [as opposed to the established

politicians and opinion leaders]. One of the things he thought and said, and that caused an

acceleration of his meteoric rise, was “Islam is a backward religion.”

It was perhaps not so important that Fortuyn said what he thought himself, but he had a knack

of saying things that many people thought and had long suppressed or refrained from saying

aloud for fear of being considered racist or xenophobic. He opened the floodgates of an

aggressive, angry and resentful xenophobic, and especially anti-Muslim, discourse that no one

has been able to shut again. He liberated feelings of which people had been ashamed. Like

Hazes, he was an emotional men who made his private emotions a public matter and thereby

won the love of a broad constituency who recognized the emotions and felt empowered and

vindicated by his bringing them out into the open. It is instructive to consider the effects of

the first time he openly said he considered Islam a backward religion. At that time he was the

figurehead and chief vote getter of a new populist party, Leefbaar Nederland (Livable

Netherlands). He probably was provoked into making a strong statement on Islam by the

journalists who interviewed him (Frank Poorthuis and Hans Wansink in De Volkskrant, 9

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 4 of 23

February 2002) and had not made it intentionally.2 (In fact, he later corrected himself and said

that most Muslims in the Netherlands are from backward parts of their countries and adhere to

backward prejudices and attitudes that do not fit in a modern liberal society.) The party was

shocked by what was then still an outrageous statement, with which it did not wish to be

associated, and it expelled Fortuyn from the party. His popularity in the polls kept rising,

however, and he established his own party to contend the May 2002 elections. Leefbaar

Nederland almost evaporated, and the Lijst Pim Fortuyn appeared poised for an

unprecedented election victory, polls predicting it would win at least 25 of the 150 seats in

parliament.

On 6 May Fortuyn was killed. The perpetrator, who was soon arrested, appeared to belong to

a radical environmentalist and animal rights group, and Fortuyn’s friends were quick in

pointing out that ‘the bullet came from the left.’ Many others were relieved that the killer was

a white Dutchman and not a Muslim immigrant. Islam was therefore not a conspicuous

element in the outpouring of public emotion after the murder. There were spontaneous

demonstrations of mourning and love of the lost leader at Fortuyn’s palatial residence in

Rotterdam; people brought flowers, dolls and other per objects that piled up in front of the

house and lighted candles. Tens of thousands came to watch the funeral, abundantly shedding

tears. Journalists noted that they represented the broad and unlikely coalition of supporters he

had been able to mobilise: “For a long time [his followers] has mainly consisted of the

inhabitants of poor urban neighbourhoods, mostly of low education and low incomes (…) and

middle class people with better jobs, incomes and cars. Meanwhile it is no longer just the

discontented, aggrieved part of the nation that has joined the following of Fortuyn. Even in

intellectual circles, where ‘professor Pim’ had not been taken seriously, he has won a degree

of sympathy” (Algemeen Dagblad 11 May 2002).3

The masses of sympathisers lining the route Fortuyn’s body took behaved in ways unknown

in the Netherlands and more reminiscent of popular devotion towards holy men in southern

2

Several years earlier, Fortuyn had written a book titled ‘Against the Islamisation of our culture’ (Fortuyn 1997;

revised version 2001). This was, however, in the first place a diatribe against multiculturalism, and it did not

contain many sweeping statements about Islam. In fact, he claimed to perceive a range of views within Islam,

from the fundamentalist to the liberal, and insisted that ‘not every form of Islam can be equated with its

fundamentalist interpretation’ (2001: 39). In an earlier newspaper interview (Rotterdams Dagblad, 28 August

2001), he had called for a ‘Cold War against Islam.’

3

This and other newspaper reports showing the broad variety of Fortuyn’s mourners, are quoted extensively in

Hart 2005: 22-23.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 5 of 23

Europe. They attempted to touch and kiss the limousine carrying his body, cried and shouted

“thank you, thank you, Pim!” People carried banners with messages, one of them saying “This

Messiah also died.” Several journalists commented on the conspicuous religious dimension of

this devotional farewell to a failed saviour. The protestant newspaper Trouw spoke of a ‘wild

devotion’ for ‘Saint Pim’ and noticed, besides the candles lighted in front of Fortuyn’s

residence, an icon of Christ about to be crucified. The Guardian saw Rotterdam turned into

one large altar on which the Netherlands honoured their martyr.4 The philosopher and

columnist Paul Cliteur commented that watching the funeral on television made him aware of

the existence of ‘an invisible religion’ connecting all those different people, a shared

consensus.5

What many had feared might happen to Fortuyn did befall Van Gogh on 2 November 2004. A

radicalised young Moroccan, well-educated and reasonably integrated, shot Van Gogh,

attempted to cut his throat and planted a written message on his body with a butcher’s knife,

leaving no doubt as to why Van Gogh was killed and who else was targeted. The killer,

Muhammad B., was discovered to belong to a group of radicalised young Muslims of mixed

ethnicity who had been planning to carry the global jihad into Dutch society. Their destructive

intentions were — fortunately — not matched by any relevant competence; in fact, their

amateurism was pitiable, but the very existence of such a group and their one successful

terrorist act, the murder of Van Gogh, had an enormous impact on Dutch society.

Van Gogh was an unlikely candidate for the saintly and heroic role as ‘martyr for the freedom

of speech’ that was suddenly ascribed to him. He was a gifted filmmaker and a newspaper

columnist with a great feeling for language but perhaps his greatest talent was that for

insulting people. In the years before his death he had frequently polemicised against Muslim

spokespersons and against Muslims in general, preferably referring to them as ‘goat-fuckers.’

This reflected his general provocative style rather than an alignment with other anti-Muslim

polemicists. He had earlier engaged in an even less tasteful polemic against a well-known

Dutch Jewish writer, Leon de Winter, in which he had not shied from outrageous comments

4

Newspaper reports summarised in Hart 2005: 23-24.

5

Paul Cliteur, “De onzichtbare religie”, in Dekker 2002: 113-118. Cliteur admittedly meant something else than

the civil religion I have been alluding to. What he thought he perceived was the a religion consisting of “the

principles that are necessary for peaceful communication between people of different backgrounds and cultural

orientation,” something like the classical fundamental laws of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the

Constitution. I do not believe the religious atmosphere of the funeral reflected anything that universal.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 6 of 23

that most people considered as anti-Semitic (Gans 1994). De Winter became one of the most

prominent anti-Muslim intellectuals but van Gogh continued heaping scorn on him, as he did

on the rabble that claimed to represent the heritage of Pim Fortuyn.6 Van Gogh had also said

outrageous things about feminism and feminists. In artistic and intellectual circles his often

rabid language was usually considered as a form of literary hyperbole, like most critics agreed

that his films betrayed, behind a provocative and controversial façade, genuine sensitivity.

The direct reason for Van Gogh’s murder was not his provocative and insulting attitude

towards Muslims (of which only the most integrated Muslims were aware anyway), but the

fact that he had volunteered to make the film Submission, that was written by Somali-born

activist and politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali to show how bad Islam is for women. The film had

been shown on Dutch television and had caused predictable anger among the Muslims who

had seen it (mostly well-integrated Muslims, again). As a former Muslim herself and a

politician actively campaigning for state intervention against the growing influence of Islam,

Hirsi Ali attracted more hatred to her person than the Dutch anti-Muslim polemicists did. She

had received death threats and was permanently protected by bodyguards. The letter planted

in Van Gogh’s body made clear that she was the real target.

The news of Van Gogh’s murder brought a broad cross-section of the population of

Amsterdam out onto the streets for a loud demonstration. The place where he had been killed

became an altar with flowers, toys, candles, banners, like that in front of Fortuyn’s residence.

From a man who had always created dissension and controversy, Van Gogh’s violent death

transformed him instantly into a symbol capable of uniting the most diverse groups in Dutch

society. Although several Muslim organisations also showed their presence and professed

their distress over the killing,7 Van Gogh became canonised as a martyr and saint in the new

cult of Dutch identity, and more strongly than after Fortuyn and Hazes, Islam now defined

this identity by being its most relevant Other.

6

Van Gogh had been friendly with Fortuyn and agreed with many of his ideas, but was very critical of the

opportunist and vulgar personnel with which he surrounded himself to establish his own party. Van Gogh’s last

feature film, completed after his death, presents a conspiracy theory about the murder of Fortuyn, implicates the

military-industrial complex, the Dutch secret service, and Fortuyn’s successor as party leader, Mat Herben. For a

clear expression of his scorn of the self-proclaimed heirs of Fortuyn, see his column ‘Corrupt Pygmies’ on his

website, http://www.theovangogh.nl/smalhout-vrienden.html.

7

Milli Görüş even issued a press statement calling Van Gogh ‘a martyr for freedom of speech’ — an effort at

damage control that may not have represented the feelings its constituency, although Van Gogh’s verbal

aggression had mostly been addressed to and perceived by Moroccan Muslims.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 7 of 23

Racism and anti-Islamism

Ayaan Hirsi Ali was forced to go into hiding for several months after the murder of Van

Gogh. Her first public reappearance was in the most prestigious political discussion

programme on Dutch television, Buitenhof, which gave her the unprecedented privilege of a

one-hour interview. She used it for a strong statement against racial and ethnic profiling as

practised by the USA after 9/11. Her alternative was ‘ideological profiling:’ the security

services should not look at a person’s skin colour or ethnic origins but should watch out for

dangerous ideologies. The one dangerous ideology was what she was to name consistently

‘pure Islam.’ Islamic terrorism was, she seemed to imply, an inevitable outcome of adherence

to ‘pure Islam,’ and only Muslims who distanced themselves sufficiently from their religion

could be trusted. In the following months she was repeatedly to emphasise that ‘liberal Islam’

did not really exist and that those who portrayed themselves a ‘liberal Muslims’ were

therefore untrustworthy hypocrites.

This is an argument that had been put forward by a number of Dutch public intellectuals

before and that, because of its apparent rejection of biological or ethnic racism, has been more

intellectually acceptable than the anti-Muslim resentment attributed to the lower classes. One

might also say that the apparent dissociation of anti-Muslim discourse from overtly racialist

discourse made the dissemination of xenophobia among the middle classes possible. Few

people in the Netherlands would be happy to be considered as racists; it was the fear of being

called racists that long made people keep silent about nuisances caused by young poor

unemployed immigrants. Fortuyn deliberately placed a few coloured people (though nonMuslims) on his list. One of Van Gogh’s best films was an empathetic narrative of an

interracial relationship. People like Hirsi Ali were, in this respect, a Godsend, legitimising

negative feelings towards Islam and Muslims and preventing guilty feelings associated with

racism. (Unsurprisingly, it has been Jewish intellectuals especially who have pointed to the

similarity of the current anti-Muslim discourse to anti-Semitic discourses of an earlier period

of Dutch national history. They were not taken in by the professed rejection of biological

racism.)

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 8 of 23

In the 1970s and 1980s, it was only politicians of the extreme fringes, the ultranationalists

Glimmerveen and Janmaat, who openly spoke out against immigrants, called for an

immigration stop and a policy of returning foreigners to their countries of origin. The former

remained completely outside the political system; the latter was elected into parliament in but

was completely quarantined by his colleagues, to whom his xenophobic utterances were (as

yet) beyond the pale. These men represented sections of the lower middle and working classes

that most directly experienced the impact of the presence of immigrant communities on their

daily lives, in competition for work and affordable housing, in the rapid deterioration of the

quality of their physical environment, and in the loss of the social world as they used to know

it. Their attitude towards immigrants (‘foreigners’) was generally considered as racist and

unacceptable — although other parties discovered that they addressed an issue of considerable

electoral appeal, and made some hesitant efforts to reframe the issue in other terms.8 On the

far left, the populist Maoists of the Socialist Party represented the voice of the same stratum,

drawing attention to the predicament the people of the old popular neighbourhoods faced.

Their anti-immigration discourse was not racist but scornful of the political elite, whose antiracism they found cheap as long as their streets remained homogenously white. The Socialist

Party were the first to warn of a cultural clash between immigrant and indigenous groups –

but they too remained isolated. Polite political discourse had no place for such statements.

In the 1990s it was the leader of the liberal party VVD, Frits Bolkestein, who first took the

debate on immigrant presence as a threat to Dutch identity into the mainstream.9 He was also

one of the first, if not the very first, to single out Islam as a prime factor in the perceived

incompatibility of immigrant and modern Western culture.10 He had been one of the fathers of

the ‘purple’ (i.e., a fusion of red and blue) socialist-liberal government coalition that presided

over eight years (1994-2001) of rapid economic growth and high employment and that

generally supported multicultural policies, but as the leader of his party’s parliamentary group

he criticised the government over the latter. He came out strongly against cultural relativism

8

See the Chapter “Neerdalen uit een ivoren toren: de Nederlandse politiek en de Centrumpartij” (“Descending

fro an ivory tower: Dutch politics and the Centre Party”), in Vuijsje 1986: 48-58.

9

Bolkestein was not really the first, but he was the first man of great prominence to do so. He had been preceded

by several years by the journalist Herman Vuijsje of the weekly HP/De Tijd, which pioneered the ‘new realism’

in Dutch public debate. His collection of essays on ‘ethnic difference as a Dutch taboo’ was the first of a long

series of ‘taboo breaking’ publications by angry white men. An excellent analysis of this wave of ‘new realism’

was made by Baukje Prins (2002, 2004).

10

See Entzinger 2003: 71-2 and Prins 2004: 25-28 on Bolkestein’s first public statement on the incompatibility

of Islam and Western values in 1991 and the ensuing debates.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 9 of 23

and multiculturalism and warned against unenlightened versions of Islam but at the same time

he entered a civilised dialogue with some intellectual Muslims (Bolkestein & Arkoun 1994;

Bolkestein 1997) and provided patronage to several secular-minded young Muslims.

Fortuyn took this a step further and moved from dialogue to Cold War against Islam —

although even he invited one Muslim spokesman who had engaged him in debate to write a

comment in the second edition of his book against the Islamisation of Dutch culture.11 As a

flamboyant, openly gay person who made no secret of his frequenting darkrooms and his

sexual encounters with Moroccan boys, Fortuyn seemed to offer his followers a rationale for

anti-immigrant resentment without making them feel narrow-minded or prejudiced. Reports

of young Moroccans taking up the old pastime of beating up cruising gays and of a Moroccan

imam calling homosexuals ‘lower than dogs and pigs’ combined in a perception of immigrant

Islam as hostile to the personal freedoms that had been achieved in civilised Dutch society.

After Fortuyn, various people closer to the political centre took up the torch. Paul Scheffer, a

former member of the think tank of the social democrat Labour Party, wrote a very influential

essay against multiculturalism in 2000, arguing that the Dutch integration policies had failed

and that “unemployment, defections from school, and criminality are piling up among the

ethnic minorities. This concerns enormous numbers of people who are lagging behind,

without any prospects, and who will constitute an increasing burden on Dutch society”

(Scheffer 2000). The new underclass, he argued, is largely ethnic and, because of its low

education and poor knowledge of Dutch caught in a trap from which upward mobility is

hardly possible. He blamed the multicultural policies of ‘integration with the preservation of

one’s culture’ for this state of affairs and accused the political elite of indifference towards

this reality.12

On the right, the philosopher and lawyer Paul Cliteur, affiliated with the liberal party VVD,

and his colleague philosopher Herman Philipse have started beating the same drum, with a

11

Imam Abdullah Haselhoef, a convert to Islam of Surinamese extraction, who briefly held much media

attention as a well-spoken Muslim leader, had a public debate with Fortuyn briefly after 9/11. He wrote a critical

review of Fortuyn’s theses, which was printed at the end of Fortuyn 2001.

12

In this essay, Scheffer makes hardly any special mention of Islam, except to observe that there exists a large

gap between the values adhered to in Muslim communities and shared behavioural norms in mainstream society,

especially in matters concerning family life. Four years later, however, he singled out ‘the malaise of Islam’ as a

threat to Dutch society (Scheffer 2004).

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 10 of 23

different emphasis: against cultural relativism and multiculturalism, in the name of

Enlightenment values. They appeared to be courting the racist resentment that had made

Fortuyn so popular but carefully restricted their critique to cultural difference: in their view

certain cultures, notably Muslim cultures, are in many respects inferior to Western culture and

therefore it would be unwise to allow those cultures to flourish in the Netherlands. The

integration of immigrants necessitates a degree of cultural assimilation, and they have to give

up attitudes that are incompatible with Enlightenment values.13 With broad sweeps and

innuendo in newspaper columns and spoken commentary on television, more subtly in

seriously intended publications, they have been hammering on the theme that not just

‘fundamentalist’ Islam but Islam as such is inherently incompatible with Western modernity.

As Cliteur writes in one of his more serious reflections, it is useful if this message is

formulated clearly and insistently by Freethinkers of Muslim background. The misgivings of

‘autochthonous’ opinion leaders about Islam may be believed to be inspired by cultural

prejudice, but the universalist statements of ‘allochthonous’ Freethinkers will make much

more of an impression (Cliteur 2002). Cliteur and Philipse have strongly pushed the public

careers of some of these immigrant Freethinkers, notably the Iranian-born lawyer Afshin

Ellian and the Somali-born politicologist and politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali — although in the

case of the latter, one might wonder who has been pushing whose career; many white opinion

leaders jumped on the bandwagon driven by Hirsi Ali.14

In her analysis of ‘new realist’ discourse, Baukje Prins identifies the following five

characteristics of the new realism: (1) the new realist presents himself (there are few women

among them; most of them are middle-aged white men) as a courageous man who dares to

face the facts and openly discusses ‘truths’ that the politically correct elite and official

discourse have hidden from view; (2) he speaks on behalf of ‘the common people,’ i.e. the

indigenous population, whose complaints have to be taken more seriously; (3) he suggests

that it is a typical aspect of Dutch character to be open-minded, honest and realistic; (4) he

believes that it is necessary to make an end to the power of the left elite, who have been

censuring public debate with their ‘politically correct’ opinions on fascism, racism and

13

Both Cliteur and Philipse are committed atheists, and Islam is not the only religion with which they take issue.

In fact, many Christians have felt that their critique of Islam and attacks on such institutions as Muslim schools

was a tactical manoeuvre in a larger strategy against the privileges granted to Christian schools in the Dutch

system.

14

Philipse 2005 is a particularly embarrassing example of an attempt to draw attention by association with her.

On the Hirsi Ali phenomenon, see Prins 2004: 143-63 and De Leeuw and Van Wichelen 2005.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 11 of 23

intolerance; (5) many a new realist poses as the real feminist, who defends the rights of

interests of immigrant, and especially Muslim, women (Prins 2004: 35-36).

In the media in general, the same shift in emphasis was noticeable: from problems with

immigrants to problems with their backward culture to Islam as the cause of all unwelcome

cultural phenomena. Female genital mutilation (FGM), honour killings and forced marriages

were ideal examples to argue against cultural relativism, and they became increasingly

identified with Islam in public debate. One normally quite sensitive newspaper columnist

(Elsbeth Etty in NRC Handelsblad) commented on what she had missed in a documentary on

Islam: the filmmaker should have shown a close-up shot of how infibulation (the most severe

form of FGM) is performed in order to inform the viewer on what that religion does to

women. Anti-Semitism, petty crime, discrimination of and violence against homosexuals,

which previously were attributed to the social problems of poor neighbourhoods and lack of

parental control were increasingly attributed to Islam as a causal factor.

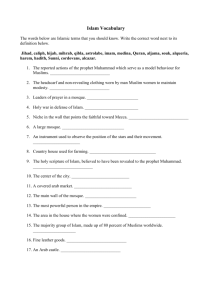

The following cartoon (from De Volkskrant, 19 January 2006) is a relatively innocent

example of the Islamisation of discourse about social problems. Two women in burqa,

with shopping bags of a cheap supermarket known to be popular among immigrants

(indicating that these are not rich Saudi women but lower-class immigrants) meet and

discuss their children. The number of Muslim women wearing face veils is estimated at

several dozen only, but a high percentage of indigenous Dutch are in favour of banning it.

The burqa in the cartoon serves at once to make the women more alien and to associate

youth violence and anti-Semitism with Islam.

— My eldest son is terrorising

homosexuals and Jews this

afternoon

— And the youngest is smashing

car windshields.

— You’re lucky to know

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

— I have no idea what mine are up

to.

Page 12 of 23

From guest workers to Muslims

Immigrants from Muslim countries, even those who have not been used to think of themselves

as Muslims, are increasingly perceived as Muslims instead of by their ethnic or class identity.

One self-evident reason for this shift is the change in composition of the communities, with

more families and elderly men, and the increasing institutionalisation of Islam. The first

‘guest workers’ had come as single men and lived initially together in barracks provided by

the factory where they worked. They interacted with Dutch society through middlemen who

acted as translators, informants for the police and consulate, travel agent etc. The first

associations were established by a handful of more politicised individuals, who established

relations with trade unions and political parties and claimed to speak for all workers of their

ethnic group (typically, Turks and Moroccans).

By the early 1970s active recruitment stopped but the government allowed family reunion:

wives and children joined the men, and diaspora communities emerged, with a new type of

needs. The first ethnic entrepreneurs arrived on the scene, offering services and products

associated with the country of origin; and improvised mosques were established, where

children were taught the basics of prayer and reciting verses of the Quran (Landman 1992;

Rath et al. 1997). In the course of the 1980s, mosque-based associations, which had a much

broader following, largely replaced the earlier left-wing workers’ organisations as

representatives of immigrant communities in contacts with the government and other Dutch

institutions. Since most mosques had clear, unambiguous ethnic affiliations, they were widely

perceived as Turkish or Moroccan institutions. In the multicultural policies adopted by the

Dutch governments of the 1980s and 1980s (see Entzinger 2003), the targeted ‘communities’

were defined by ‘nationality’ or origin. (This meant that Kurds in the Netherlands were

treated as Turks, Iranians, Iraqis or Syrians. Only non-Muslim minority groups such as the

Syrian Christians from Turkey were treated as distinct communities.)

Further institutionalisation of Islam — the establishment of Muslim schools, a Muslim

broadcasting association, various representative bodies aiming to act as the interface between

local and national government and the immigrant communities — contributed to the shift

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 13 of 23

from ‘ethnic’ to ‘religious’ group identification. The fact that such an identification fitted the

Dutch ‘pillar’ system (which remained in place in the fields of education and broadcasting)

better no doubt played a part. Inter-ethnic organisations emerged (although they never became

dominant; most new Muslim institutions retained strong ethnic character). As a corollary,

most of the ‘ethnic’ communities broke up into one or more religiously defined groups and

those resolutely rejecting a religious label (among the Turks, the Alevis organised themselves

separately, and Kemalists and Marxists kept maximal distance from Muslim associations).

Given the relatively low percentages of (nominal) Muslims who are reported as regularly

practising their religion — in Rotterdam, 26% of the Turks and 44% of the Moroccans

interviewed in a survey claimed to follow the prescriptions of their religion (Phalet et al.

2000: 22) — it is not immediately evident why the Dutch began to perceive them as Muslims

instead of Turks and Moroccans, etc. The increasing popularity of the headscarf among young

women no doubt played a part — in the course of the 1990s this rapidly conquered public

spaces; and it was generally perceived as a religious rather than an ethnic marker. But the

international context also had a strong impact on perceptions. Ideas from Bernard Lewis’ and

Samuel Huntington’s influential articles on the ‘roots of Muslim rage’ and the ‘clash of

civilisations’ filtered through into popular discourse and perception. The terrorist attacks in

New York, Madrid and London made Islam rather than ethnicity a reason for caution.

In the previous section I suggested that the shift in discourse on immigrants from references to

ethnic origin or class to culture and especially Islam coincided with, and was perhaps

correlated with, the social rise and increased social acceptance of anti-immigrant resentment.

This is not the only or even the most important factor in this process but it deserves more

attention than it has received so far. There are moreover some indications that the opinion

leaders who have framed the problems with immigrants and (allegedly) failing integration in

terms of Islam have had an impact on those segments of the population that were already

prejudiced and did not need the cultural argument as justification. As far as can be judged

from newspaper reporting, people living in neighbourhoods with large proportions of

immigrants are also increasingly framing their unease in terms of Islam rather than ethnicity.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 14 of 23

‘New realist’ intellectuals, ‘ordinary people’, and Muslim radicalisation

Recent sociological research on attitudes towards immigrants in the Netherlands suggests that

prevalent negative attitudes cannot simply be explained by the common pattern of (interethnic) prejudice. Factor analysis of responses to a questionnaire delivered by telephone to

over 2000 indigenous Dutch respondents showed up two major factors. One of them

corresponded with prejudice as found consistently in studies of interethnic relationships in

other contexts too. The second factor corresponds, in the authors’ words with “negative

judgement based on a cultural conflict about which both groups are in agreement,” and it

concerns especially the treatment of women and children. They refer to an earlier survey

among indigenous Dutch, Moroccans and Turks in Rotterdam by Phalet et al. (2000), which

found that the Dutch object to the way Moroccan and Turkish men behave towards their

wives and children, whereas the Moroccans and Turks object to what they consider as the

decadent laxity of the Dutch in these matters. Both sides agree that they have a conflict over

values.

The authors appear to believe that this factor is responsible for negative attitudes towards

immigrants among the better-educated respondents (interestingly, they speak of ‘Muslims’

and ‘Muslim culture’ although their respondents were selected on the basis of nationality of

origin). If I read them correctly, they believe that their data shows that the arguments of the

‘new realists’ discussed above are not simply rationalisations of prejudice but reflect an

essentially different attitude from that of ordinary prejudiced people. (They write: “…

respondents taking exception to these cultural practices [towards women and children]

without rejecting Muslim immigrants are among the least prejudiced and most educated in the

Netherlands.”) Ordinary prejudice may decrease when people come to know members of the

other group better; the negative attitudes associated with the second factor, one would

surmise, are unlikely to decrease as a result of more contact with the other group. The

acceptance of ‘Muslims,’ the researchers imply, will not take place unless they change their

attitudes in these key areas of family life.

An experiment performed in the context of the same research project singled out social

conformism as a major factor in attitudes towards immigrants and suggested that whatever

politicians or other persons of authority say on the matter of immigration and integration has a

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 15 of 23

great influence on a considerable segment of the population (Hagendoorn and Sniderman

2004). A number of attitudinal traits were measured, including self-esteem, national

identification, perception of cultural threat, appreciation of the Netherlands, social

conformism and acceptance of authoritarian values. National identification proved to be

negatively correlated with the degree of self-esteem (suggestion that compensation

mechanisms are at work), but also with the degree of appreciation for the Netherlands. Social

conformism, and secondarily authoritarianism, appeared to be the central factors. Both

national identification and the perception of cultural threat are strongly correlated with social

conformism. People scoring high on social conformism — roughly a third of the respondents

— have negative attitudes towards all deviant behaviour, irrespective of its substance. The

authors conclude that the perception of cultural threat is based on the rejection of difference,

not on a rejection of the different values as such.

‘Strong’ conformists had more negative attitudes towards immigrants than ‘weak’ conformists

to begin with, but they were also easily influenced by even moderate amounts of social

pressure. Interviewees were confronted with statements on integration and multiculturalism,

attributed to politicians of their own or opposite parties. The effect of statements attributed to

a politician of their own colour had a very strong effect on ‘strong’ conformists, irrespective

of their political orientation (liberal-conservative or social democrat) and irrespective of the

direction in which pressure was exerted. Summarising three such experiments with persuasive

pressure from government, from peers and from political leaders on questions of cultural

diversity, the authors reported that social conformists markedly yield to this pressure from all

three sources. They concluded that this “exposes an unexpected freedom of maneuver for

politicians to guide public opinion about such key issues as tolerance and support for

multiculturalism” (Hagendoorn and Sniderman 2004).

It is risky to extrapolate from this relatively simple experiment to complex social realities, but

these research findings appear to support the claim that the media and opinion leaders seeking

media coverage have played key roles in the dramatic and rapid shift in public discourse about

immigrants, integration and Islam. They appear to give a partial explanation of what even the

casual observer of the Dutch scene cannot help witnessing. The ‘new realism’ with its urge to

break taboos and clear away the remnants of ‘political correctness’ has been self-perpetuating

and self-accelerating at a pace where yesterday’s most outrageous taboo-breaking statement

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 16 of 23

already sounds tame today.15 ‘New realist’ columnists and politicians, it appears, have

persuaded ordinary, somewhat prejudiced people that their prejudices (and fears) are justified

and that they can express them without fear. Politicians are outdoing each other in expressing

what they believe the common people think. With such positive feedback loops, public

discourse keeps radicalising.

Inevitably this also affects the attitudes of members of the immigrant communities. Many

who had thought of themselves primarily in ethnic, class or professional rather than religious

terms found that, being discriminated against as Muslims they had to live with this Muslim

identity. Those who were pious Muslims — and probably quite a few who were not — were

tempted to reject the society that refused to accept them; some actually decided to turn against

it. The Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD), in one of its reports on

radicalisation among young Muslims, pointed to the anti-Muslim discourse of politicians and

columnists as a major contributor to the alienation of young Muslims from Dutch society and

to their radicalisation. Unsurprisingly, the bolder ones among the ‘new realists’ accused the

AIVD of political correctness and of wishing to silence the freedom of expression. Many

judged that this was reason to increase the pressure and break further taboos. (One columnist,

however, Paul Cliteur, decided to abstain from public statements about Islam.)

Evidence of the impact of the new realists’ rhetorical fireworks on the radicalisation of young

Muslim immigrants is anecdotal. The small group of radicalised young men and women to

which Van Gogh’s murderer belonged clearly was strongly affected by this discourse. They

followed the Dutch media and were quite aware of who the major new realists and antiMuslim polemicists were. Their rejection of Dutch society was a response to the perceived

disrespect this society showed Islam. The list of politicians threatened with death, with names

like Hirsi Ali and another liberal anti-Muslim politician, Geert Wilders, suggests that their

radicalisation had something to do with anti-Muslim discourse. The voices of moderates,

insofar as they let themselves be heard, also indicate a profound disenchantment with Dutch

society due to the hardened discourse of the past few years.

15

Several observers have commented that statements for which right-wing populist Janmaat was indicted and

sentenced in court (like “when we come to power we shall abolish multicultural society”) are very innocent and

reasonable compared to what has now become mainstream discourse.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 17 of 23

The press may have been part of the mechanism producing polarisation and radicalisation,

and the voices reported in the press may not be entirely representative of encounters and

debates in everyday life at the grassroots level. An experiment with discussions in focus

groups imitating possible real life situations may yield some new insights into the dynamics

of the debate.

The Ethno-barometer project

In order to gauge the tensions and attitudes at the grassroots level, discussions on questions

related to matters of cultural diversity were organised in controlled situations, in focus groups

that in their composition more or less represented the variety of population in real-life

encounters. Thus far, four focus groups in the same middle-sized Dutch town have been

convened from three consecutive discussion sessions each.16

Gouda, a town of some 70,000 inhabitants, has a large immigrant population (almost 20%, of

whom 10% of Muslim background), Moroccans with some 6,000 constituting the largest

group (the second largest immigrant group is the Germans; Turks are a much smaller group of

only 400). In Gouda, Moroccan and Muslim identity are therefore almost coterminous. There

has been a history of conflict in several districts of the city. Right-wing and xenophobic

populists have a certain following in Gouda, though they are less prominent (and perhaps less

radical?) than in Rotterdam. The main reason to choose Gouda, however, was that the chief

researcher had an extensive network of contacts here as a result of previous research and

social work among Moroccan youth.

Each focus group consisted of approximately 10-15 people and had a heterogeneous

composition. In each at least a third were of Moroccan background; two focus groups also had

a Dutch convert. The ages varied from students to pensioners. Among the indigenous Dutch

members, conservative Christians (who are prominently present in Gouda) were wellrepresented but there were also progressive Christians and the remainder were mostly of

leftist (socialist) orientation. Efforts had been made to recruit also a number of right-wing

Dutch nationalists to take part in this project; these refused, but some of them stated the

16

This research is part of the larger, internationally comparative Ethno-barometer project “Europe’s Muslim

communities: Security and integration post 11 September,” that is co-ordinated by Alessandro Silj. The Dutch

part of the project was carried out by ISIM; the chief researcher was Martijn de Koning.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 18 of 23

reasons for their refusal in writing, without munching words. They were convinced that ‘the

Moroccans’ had come to the Netherlands in order to take control of it and that talking with

them was useless.

“During these conversations, Muslims will act as poor human beings and the Dutch

people are guilty. During these conversations it comes down to the fact that we people

from Gouda have to leave everything, giving all our money to them, let them rape our

women, let them rob and abuse our children. If not, they stab you; they will destroy

your windows, and beat your car to ruin! I have had these talks in Gouda. I am fed up

with these talks. It doesn’t help a fuck! They have a free ticket from the state and they

can do whatever they want. And do you know how it ended? That [the police] wanted

to fine me because I gave my opinion and you can’t do that, not even if you can prove

that they cheat. So have a lot of fun with your discussions and wasting your time on

useless things. There is only one solution, to throw the whole bunch out of the

country” (response of one non-respondent, summarily translated by Martijn de

Koning).

Each focus group was given a specific range of themes to discuss (media and representation,

politics, Islam in the public sphere, education). A moderator introduced the theme and steered

the discussion so as to draw out all arguments and have to participants express themselves

freely but also reflect on what others said. One striking aspect was that the tone in the

discussions, even when there were strong disagreements, remained quite polite in comparison

with the debates on finds in the Dutch media. In three of the focus groups, people were clearly

holding back and refrained from expressing their most negative feelings — which is an

interesting observation in itself: in face-to-face relations, the self-restraint that the ‘new

realists’ have been clearing away in the media is still an attitude that comes naturally to

people. In the fourth group, there were stronger tensions between (some of) the non-Muslim

and the Muslim participants, which could rapidly escalate. One time, when the discussion

between two opponents became particular heated, the moderator suggested a brief coffee

break. The research team was surprised to see that the two opponents during the break

spontaneously approached each other and said some friendly words to one another, deflating

the tension. So even here the fact that the opponents were not abstractions but concrete

individuals (with a personality that cannot be reduced to a single opinion) appeared to make

bridging easier. This does not mean that dialogue bridges all differences and

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 19 of 23

misunderstandings; one of the non-Muslim participants told the research team he would no

longer tsake part because he could not stand one of the other participants, a non-Muslim

woman.

One issue that surfaced in all groups was that both indigenous Dutch and Moroccans expected

more understanding, flexibility, and adaptability of the other group. Repeatedly Dutch

participants told Moroccans that they wished to see a clear sign of their opting for Dutch

society – by giving up dual nationality, decreasing their ties with Morocco, etc. Several of the

Dutch participants admitted that international terrorism, problems with obnoxious Moroccan

youth, and Islam were somehow connected. Especially when young Dutch Moroccans grow a

beard and don Muslim attire, they just look like the terrorists on television. Most of the Dutch

felt, they admitted with some difficulty, a certain fear of Muslims and wanted the Moroccans

to understand why this was the case. They also thought that Muslims were too easily hurt and

tended to present themselves as victims in all situations.

Several Moroccans complained that the Dutch always wanted adaptation to be unilateral; life

would be much easier, they said, if the Dutch also would make some effort to understand and

show some respect to values that are important to Muslims. (The example mentioned was the

female minister Verdonk threatening an imam who refused to shake hands with her, with

television cameras watching: couldn’t she have behaved less insensitively?) They complained

of discrimination and humiliation, and they showed irritation that the Dutch did not wish to

see that Muslims are in fact often victimised.

All participants, Muslims and non-Muslims alike, agreed that immigrants, Muslims and Islam

are given a very unfair deal in the media, which they perceived as reporting too negatively.

They blamed journalists and politicians for fanning the tensions between Muslims and nonMuslims in Dutch society. “When there is some negative news concerning Moroccans, they

are called Moroccans,” one said, “but when the news is more positive they are called Dutch.”

Offensive behaviour by Muslims is frequently associated with terrorism. Some of the Muslim

spoke of double standards on the matter of freedom of expression: the Dutch defend Salman

Rushdie’s and Theo van Gogh’s right to insult Muslims, but not the Moroccan imam El

Moumni’s right to insult homosexuals and call them “lower than pigs.” The Dutch

participants agreed that there were many prejudices in Dutch society, but most of them

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 20 of 23

appeared to see these in other Dutch persons and (conveniently?) the media, not so much in

themselves.

At many moments during the discussions, the major fault line within the focus groups was

that between Muslims and non-Muslims (or Moroccans and non-Moroccans; the Dutch

participants tended to use the terms ‘immigrants’, ‘Moroccans’, ‘Muslims’ or even

‘minorities’ interchangeably, and the Moroccans occasionally objected to this general

identification; certain issues, for them, were immigrant issues that had nothing to do with

Islam; others concerned them specifically as Moroccans or as Muslims). Repeatedly,

however, the Dutch participants noted that the Moroccans did not share the same opinion on a

sensitive issue, such as homosexuality or freedom of expression. On other issues, the

conservative Christians sided with the religious Muslims against the secular Dutch. Of the

various potential fault lines (religious / ethnic identity, age, class, degree of religiosity) the

one between Muslims (including the nominal, hardly practising Muslims) and non-Muslims

was most often and most easily activated.

Conclusion

The perception that Dutch culture is under threat appears to be more widespread than an

awareness of what this culture consists of. The notion appears capable of mobilising large

masses in manifestations that have strongly religious atmosphere. The cult of the three new

national martyrs Pim, Theo and André (whom one is tempted to see as the father, the son and

the holy spirit of a new religious cult), is accompanied with calls for conformity. Muslims, it

seems, are not by definition excluded, but have to give proof of their loyalty if they wish to

belong. The new realists, who are still dominating much of public discourse on Islam in the

Dutch media, appear to insist that Muslims have to distance themselves from Islam in order to

be admitted. In discussions at the local level proof of loyalty is also demanded, but in the less

drastic form of opting for Dutch citizenship and adapting to Dutch habits. The notion that

integration demands adaptations from both sides appears to be submerged.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 21 of 23

References

Adriaansens, H.P.M. et al. (2005) 'Eenheid, verscheidenheid en binding. Over concentratie en

integratie van minderheden in Nederland', Den Haag: Raad voor Maatschappelijke

Ontwikkeling.

Bellah, Robert (1970) 'Civil religion in America', in Robert Bellah (ed.), Beyond belief, New

York: Harper & Row, pp. 168-89.

Beunders, Henri (2002) Publieke tranen. De drijfveren van de emotiecultuur, Amsterdam:

Contact.

Blokland, Claudia (2005) 'André bedankt. 50.000 fans, 500 vrijwilligers, 5.000.000 kijkers, 1

media fenomeen, en heel veel tranen', doctoraalscriptie, Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Bolkestein, Frits (1997) Moslim in de polder: Frits Bolkestein in gesprek met Nederlandse

moslims, Amsterdam: Contact.

Bolkestein, Frits (2003) 'De islam is niet gevaarlijk: West-Europa is vijand van zichzelf', Vrij

Nederland, 64, no. 18 (3 May): 18.

Bolkestein, Frits and Arkoun, Mohammed (1994) Islam en de democratie: een ontmoeting,

Amsterdam: Contact.

Buijs, Frank and Rath, Jan (2002) 'Muslims in Europe: the state of research. Essay prepared

for the Russell Sage Foundation, New York City, USA', Amsterdam: Department of

Political Science / IMES.

Cliteur, Paul (2002) Moderne Papoea's: dilemma's van een multiculturele samenleving,

Amsterdam & Antwerpen: Arbeiderspers.

Cliteur, Paul (2004) God houdt niet van vrijzinnigheid. Verzamelde columns en

krantenartikelen 1993-2004, Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

Dekkers, Peter (ed.) (2002) Nederland na Fortuyn, Amsterdam: Rainbow Pocketboeken /

Dagblad Trouw.

Derksen, Guido (2005) Hutspot Holland: gesprekken over de multi-etnische staat van

Nederland, Amsterdam/Antwerpen: Atlas.

Entzinger, Han (2003) 'The rise and fall of multiculturalism: the case of the Netherlands', in

Christian Joppke and Ewa Morawska (ed.), Toward assimilation and citizenship:

immigrants in liberal nation-states, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 59-86.

Ephimenco, Sylvain (2004) Het land van Theo van Gogh: de multiculturele desintegratie,

Antwerpen/Amsterdam: Houtekiet.

Fortuyn, Pim (1997) Tegen de islamisering van onze cultuur. Nederlandse identiteit als

fundament, Utrecht: Bruna.

Fortuyn, Pim (2001) De islamisering van onze cultuur. Nederlandse identiteit als fundament,

met een kritische reactie van Imam Abdullah R.F. Haselhoef, Rotterdam: Karakter

Uitgevers B.V.

Fortuyn, Pim (2002) De puinhopen van acht jaar paars, Uithoorn: Karakter Uitgevers.

Gans, Evelien (1994) Gojse nijd en joods narcisme: de verhouding tussen Joden en nietJoden in Nederland, Amsterdam: Platina Paperbacks.

Hagendoorn, Louk and Sniderman, Paul (2004) 'Het conformisme-effect: sociale

beïnvloeding van de houding ten opzichte van etnische minderheden', Mens en

maatschappij, 79 no.2: 101-23.

Hart, Joep de (2005) Voorbeelden en nabeelden: historische vergelijkingen naar aanleiding

van de dood van Fortuyn en Hazes, Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Huntington, Samuel P. (1993) 'The clash of civilizations?' Foreign Affairs, 72 no.3: 22-49.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 22 of 23

Jansen, Hans (2003) God heeft gezegd. Terreur, tolerantie en de onvoltooide modernisering

van de islam, Amsterdam & Antwerpen: Uitgeverij Augustus.

Jaspers, Eva and Lubbers, Marcel (2005) 'In spiegelbeeld: autochtone houdingen in allochtone

perceptie en AEL-stemintentie', Mens en Maatschappij, 80 no.1: 4-24.

Korteweg, Anna C. (2005) 'De moord op Theo van Gogh: gender, religie en de strijd over de

integratie van migranten in Nederland', Migrantenstudies, 21 no.4: 205-23.

Landman, Nico (1992) 'Van mat tot minaret: de institutionalisering van de islam in

Nederland', Ph.D. thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht.

Lane, Christel (1981) The rites of rulers: ritual in industrial society - the Soviet case,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leeuw, Marc de and Wichelen, Sonja van (2005) '‘Word alsjeblieft wakker!’: Submission, het

fenomeen ‘Ayaan’ en de nieuwe ideologische confrontatie’, Tijdschrift voor

Genderstudies, 8 no. 4: 44-58.

Lewis, Bernard (1990) 'The roots of Muslim rage', The Atlantic Monthly, 266 no. 3: 47-60.

Mak, Geert (2005) Gedoemd tot kwetsbaarheid, Amsterdam: Atlas.

Pels, Dick (203) De geest van Pim: het gedachtegoed van een politieke dandy, Amsterdam:

Anthos.

Phalet, Karen, Lotringen, Claudia van and Entzinger, Han (2000) 'Islam in de multiculturele

samenleving. Opvattingen van jongeren in Rotterdam', Utrecht: ERCOMER.

Philipse, Herman (2005) Verlichtingsfundamentalisme? Open brief over Verlichting en

fundamentalisme aan Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

Prins, Baukje (2002) 'Het lef om taboes te doorbreken: nieuw realisme in het Nederlandse

discours over multiculturalisme', Migrantenstudies, 18: 241-54.

Prins, Baukje (2004) Voorbij de onschuld: het debat over integratie in Nederland (Tweede,

geheel herziene en uitgebreide druk), Amsterdam: Van Gennep.

Rath, Jan, Sunier, Thijl and Meyer, Astrid (1997) 'Islam in the Netherlands: the establishment

of Islamic institutions in a de-pillarizing society', Tijdschrift voor Economische en

Sociale Geografie, 88 no. 4: 389-95.

Scheffer, Paul (2000) 'Het multiculturele drama', NRC Handelsblad, 29 Januari 2000:

Scheffer, Paul (2004) 'Het onbehagen in de islam', Trouw, 18 september 2004:

Shadid, W.A.R. and Koningsveld, P.S. van (1990) Moslims in Nederland: minderheden en

religie in een multiculturele samenleving, Houten/Diegem: Bohn Stafleu Van

Loghum.

Sniderman, Paul, Hagendoorn, Louk and Prior, Markus (2003) 'De moeizame acceptatie van

moslims in Nederland', Mens en Maatschappij, 78 no.3: 199-217.

Sniderman, Paul, Hagendoorn, Louk and Prior, Markus (2004) 'Predispositional factors and

situational triggers: exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities', American

Political Science Review, 98: 35-49.

Vuijsje, Herman (1986) Vermoorde onschuld: etnisch verschil als Hollands taboe,

Amsterdam: Bert Bakker.

Wal, Jessika ter (2004) 'Moslim in Nederland. De publieke discussie over de islam in

Nederland: een analyse van artikelen in de Volkskrant 1998-2002', Den Haag: Sociaal

en Cultureel Planbureau.

2006 – WS 10 – van Bruinessen

Page 23 of 23