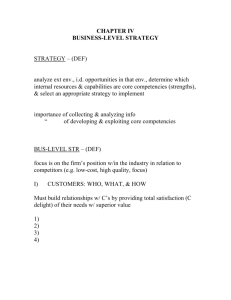

BUSINESS-LEVEL STRATEGIES AND PERFORMANCE IN A

advertisement