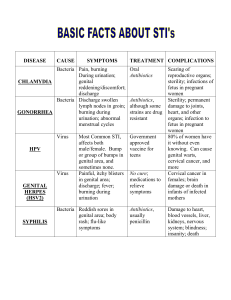

Female Genital Cutting

advertisement