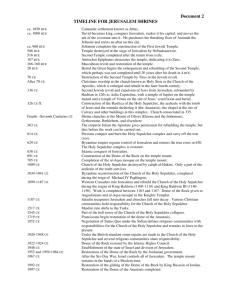

The Visitatio Sepulchri in the Latin Church of the Holy Sepulchre in

advertisement