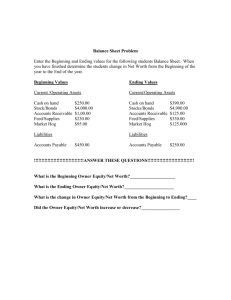

Financial Statement Overview & the Balance Sheet

advertisement

CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Module Outline Objectives Introduction to the Income Statement The Income Statement Entity and Timing Cash and Accrual-adjusted Income Statements Cash to Accrual Analysis Case Example Cash to Accrual Analysis Test Drive Other Adjustments Verifying Income Statement Information Statement of Owner Equity Statement of Owner Equity Case Analysis Objectives This module will focus on the income statement and statement of owner equity which are critical in determining sources of earnings. The specific objectives are to: • • • • Provide an introduction to the income statement and show how it is used by producers and lenders Second, illustrate how one can quickly convert a Schedule F Tax statement to an accrual-adjusted income statement using beginning and ending balance sheets. Understand the difference between cash and accrual statements and how accrual analysis can be used to improve lending decisions. Reconciling the information on the income statement and balance sheet through the statement of owner equity. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 1 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Introduction In agricultural credit analysis and in some cases small business loan analysis, decisions for loan requests are frequently made by using solely the Schedule F: Profit or Loss from Farming or Schedule C: Profit or Loss from Business tax forms. However, these statements filed for Internal Revenue Service compliance can often be misleading when evaluating the actual performance of a business, particularly in conducting commercial loan analysis, where much of the portfolio risk exists. The income statement, also called the profit and loss statement, is a better depiction of financial performance. Income statements can be prepared in-house by the businessperson or by a bookkeeper, accountant or CPA. Generally a higher level of accounting sophistication is needed when complex business entities or large loan requests are involved due to higher risk levels. An income statement is used to measure revenue and expenses during an accounting period. For agriculture it is generally dated January 1 to December 31; however, larger more complex businesses may have quarterly statements or different fiscal years, such as July 1 to June 30. An income statement differs from the balance sheet in that it reports income measured over a period of time, rather than at a specific point in time. The Income Statement The income statement can be used to: • Determine income tax payments and develop tax strategies • Analyze a firm’s expansion or growth potential and possible acquisitions • Examine business transition and management succession • Evaluate the profitability of business activities or a shift in enterprises • Justify loan repayment ability, from a business standpoint • Assist in establishing buy-sell agreements, business organization procedures and possible exit strategies Just as for the balance sheet, many different formats can be used in constructing an income statement, but regardless of the format that is used, the statement should include two major categories: revenues and expenses. Some categories of revenues that may be included on the income statement are: • Realized cash revenues from the sale of agricultural commodities • Unrealized income resulting from changes in the quantity or price of crop and livestock inventories • Realized capital gains from the sale of capital assets, like machinery, livestock, land and improvements • Income from custom work and government payments Most income statements do not include the rental value of farm dwellings as a measure of income. Likewise, most preparers exclude unrealized changes in the value of capital assets from an income statement. However, changes in quantity of crop and livestock Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 2 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity inventories are included in the income statement. The Farm Financial Standards Council (FFSC) recommends that a charge for unpaid family labor and management should not be included on the income statement. Also, off farm earnings should not be included on the income statement for the agricultural business because they were not generated through the use of business assets. The FFSC continues to recognize both the gross revenue and value of farm production (VFP) approaches for preparation of the income statement. Value of farm production is a measure of the value an agricultural operation has added to products sold and is determined by subtracting from gross revenue the cost of purchased assets that were subsequently sold to produce all or part of the total revenues. The most common examples are the cost of feeder livestock purchased and the cost of feed purchased. The gross revenue approach to presenting the income statement is the most common, but the VFP approach still has merit for certain types of operations. Entity and Timing Like a balance sheet, an income statement can be constructed on a business, personal, or consolidated basis. Because of the interrelationship between a balance sheet and income statement, the balance sheet and income statement should be constructed for the same entity; if a balance sheet is constructed for the business only, then the income statement should include only business revenue and expenses. As previously mentioned, the accounting period covered by an income statement can be any length of time. The common period used by agricultural producers is one year, but monthly and quarterly income statements are sometimes prepared as well. For example, large, complex vegetable and horticultural operations may utilize monthly and in some cases weekly statements. The accounting period covered by the income statement should coincide with the time between the beginning and ending balance sheets. Cash and Accrual-Adjusted Income Statements The two basic types of income statements are cash and accrual-adjusted statements. A cash income statement measures revenues only when received and expenses only when paid. The cash income statement is most commonly used by the smaller traditional and lifestyle farm or segments. Since very few producers select the accrual accounting option for tax preparation, the Schedule F is often referred to as a cash based income statement. See Exhibit 1 for a typical example of a cash basis Schedule F as presented for Ted Greene. This statement is readily available since the IRS requires it if the business generates income. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 3 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 1: Schedule F for Ted Greene Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 4 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity A Schedule F tax statement can be valuable if three to five years of information are analyzed and a farm has a stable existence, with no major adjustments or changes in the Federal tax laws, like modified accelerated depreciation rules allowed by the IRS. This is because the shifting of revenue and expenses will generally even out over the years. However, rules regulating the completion of the cash basis Schedule F statement allow a producer to utilize tax strategies to defer taxes to the future. Thus, a single cash basis Schedule F is not a “good” indicator of profitability. The use of depreciation on cash income statements is very controversial. Some argue that is not a cash outlay and should not be included. Others state that depreciation is merely a method of capitalizing the cost of capital assets over the useful life and should be included. One must be aware that methods of depreciation and tax laws can misconstrue the interpretation of the income statement from a cash standpoint. However, because depreciation is included on the Schedule F it is commonly used on cash statements. An accrual-adjusted income statement measures revenue when generated and expenses when incurred, even when revenue and expenses are not cash. Accrual based statements are better indicators of profitability for the operating period. Unfortunately, accrual based statements are only normally prepared for very large and complex businesses. Thus, lenders often have to convert the cash based information that is provided into an accrual-adjusted income statement. Exhibit 2 illustrates the adjustments needed to convert information reported on a cash statement to an accrual-adjusted income statement. This method, though not perfect, provides a practical method for making the necessary adjustments. This accrual-adjusted statement is recommended by the FFSC and is a must for farmers making major adjustments, like expansion or contraction, or the larger, megafarm operations. It is recommended, if at all possible, that an accrual-adjusted statement be used to obtain a more accurate picture of the profitability of the farm business. In order to prepare the accrual-adjusted income statement, it is necessary to have consistently prepared balance sheets as of the beginning and ending dates of the income statement period. If the balance sheets do not match the accounting period for the income statement, one must have records that document transactions, such as sales, inventory, production, and expenses, to ascertain the differences. This can be a time consuming and painstaking process. After the balance sheet adjustments are made, the gains and losses from the sale of capital assets are added to or subtracted from the net farm income from operations (NFIFO) to calculate net farm income. The resulting accrual-adjusted net income should be similar to what an accountant prepared accrual based income statement would reflect. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 5 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 2: Adjustments Needed for Conversion From Cash to Accrual Basis Year ending 12/31/YY Schedule F Net Cash Farm Income (Profit or Loss) Proceeds from sales of culled breeding livestock* + + Big Three Increase in inventory (livestock & crop) Decrease in inventory (livestock & crop) Increase in accounts receivable Decrease in accounts receivable Increase in accounts/rent payable Decrease in accounts/rent payable + + + Minor Two Increase in prepaid expenses (investment in growing crops, supplies) Decrease in prepaid expenses (investment in growing crops, supplies) Increase in accrued expenses (taxes, interest, etc.) Decrease in accrued expenses (taxes, interest, etc.) + + Accrual adjusted Net Farm Income from Operations Gain/loss from sale of farm capital assets excluding culled breeding livestock** Accrual-adjusted Net Farm Income $0 $0 *Found on tax form 4797 of income tax return "normal culling practices" ** Normal capital transactions (i.e. machinery, equipment, real estate) *** "+" increases accrual-adjusted net income, "-" reduces accrual-adjusted net income. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 6 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Big Three and Minor Two Dean Duelke, a former banker and consultant who currently provides training to lenders on financial and cash flow analysis, refers to the five balance sheet accounts as the Big Three and Minor Two. These five accounts are also the same accounts that he adjusts in order to convert accrual profits to operational cash flow. The Big Three are: • Inventory (crop and livestock) • Accounts receivable • Accounts payable The Minor Two are: • Prepaid expenses (supplies, investment in growing crops) • Accrued expenses (including interest, taxes, wages, and rents) From a management standpoint, accrual taxpayers calculate taxes considering adjustments to these five accounts. The cash basis taxpayer calculates taxes without adjusting for these five accounts. This is an important concern to the customer and lender in that the cash based taxpayer defers income taxes in times of growth and repays them in times of constriction or profit suppression. This deferred tax is like an interest free loan from the government so it is very attractive to the borrower. This practice is particularly detrimental to an asset-based lender, who bases the loan decision on collateral and balance sheet position rather than cash flow and earnings. The producer who is facing financial stress can least afford to prepay expenses or forgo collection of receivables and sale of inventory, creating a catch-22 in cash flow. Exhibit 2 illustrates how a change in one of the five balance sheet accounts impacts accrual-adjusted net income. For example, an increase in livestock inventory is treated as an increase in revenue, even if that inventory is not sold. A decrease in inventory likewise reflects a decrease in revenue. Changes in inventory can result from price or quantity changes individually or combined. It is important for lenders to distinguish among the reasons for the change. This is why schedules that list quantities as well as prices or values placed on crop or livestock inventory should accompany the balance sheets. Exhibits 3 and 4 show beginning and end of the year balance sheets for Ted Greene. These statements and the Schedule F tax statement will be used to illustrate cash to accrual analysis. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 7 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 3: Beginning Balance Sheet Balance Sheet Ted Greene As of December 31, Year XX ASSETS LIABILITIES CURRENT ASSETS Cost Market Value CURRENT LIABILITIES Cost Market Value Cash Savings Marketable securities Accounts receivable Livestock to be sold Crops and feed Cash investment in crops Supplies Prepaid expenses $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 2,000 5,000 4,000 2,000 50,000 70,000 4,000 2,000 2,000 2,000 5,000 12,000 2,000 125,000 70,000 4,000 2,000 2,000 Accounts payable Operating loans due within 1 year Principal portion of long-term debt due within 1 year Accrued interest & expenses Estimated accrued taxes Accrued rents payable Deferred tax liability on current assets including marketable securities $ $ 6,000 50,000 6,000 50,000 $ $ $ $ 20,000 12,000 10,000 1,500 20,000 12,000 10,000 1,500 Total Current Assets $ 141,000 224,000 Total Current Liabilities $ 99,500 143,555 $ $ 50,000 10,000 50,000 10,000 NON-CURRENT ASSETS Intermediate Assets Machinery and equipment Cost 200,000 Acc. Dep. 80,000 Breeding stock Cash value in life insurance Securities not readily marketable Fixed or Long-Term Assets NON-CURRENT LIABILITIES Intermediate Liabilities 250,000 $ 120,000 $ 40,000 $ 10,000 $ 4,000 Farm real estate and buildings Land Buildings and improvements Cost 100,000 Acc. Dep. 30,000 $ Total Non-Current Assets $ 644,000 Total Assets 44,055 40,000 10,000 4,000 700,000 $ 400,000 Machinery & equipment loans (principal due beyond 12 months) Life insurance policy loan Deferred tax liability on: Machinery Breeding stock Long-Term Liabilities Real estate and building loans (principal due beyond 12 months) Deferred tax liability on: real estate and buildings 42,900 13,200 $ 200,000 200,000 75,900 70,000 $ 785,000 1,004,000 1,228,000 Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum Total Non-Current Liabilities $ 260,000 392,000 Total Liabilities $ 359,500 535,555 Owner's Equity $ 425,500 692,445 Total Liabilities + Owner's Equity $ 785,000 1,228,000 8 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 4: Ending Balance Sheet Balance Sheet Ted Greene As of December 31, Year YY ASSETS LIABILITIES CURRENT ASSETS Cost Market Value CURRENT LIABILITIES Cash Savings Marketable securities Accounts receivable Livestock to be sold Crops and feed Cash investment in crops Supplies Prepaid expenses $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 3,000 6,000 4,000 3,000 45,000 65,000 4,500 2,000 2,500 3,000 6,000 13,000 3,000 120,000 65,000 4,500 2,000 2,500 Accounts payable Operating loans due within 1 year Principal portion of long-term debt due within 1 year Accrued interest & expenses Estimated accrued taxes Accrued rents payable Deferred tax liability on current assets including marketable securities Total Current Assets $ 135,000 219,000 Total Current Liabilities NON-CURRENT ASSETS Intermediate Assets Machinery and equipment Cost 220,000 Acc. Dep. 100,000 Breeding stock Cash value in life insurance Securities not readily marketable Fixed or Long-Term Assets Farm real estate and buildings Land Buildings and improvements Cost 100,000 Acc. Dep. 35,000 Total Non-Current Assets Total Assets Cost Market Value $ $ 2,500 60,000 2,500 60,000 $ $ $ $ 30,000 13,000 11,000 1,500 30,000 13,000 11,000 1,500 43,890 $ 118,000 161,890 NON-CURRENT LIABILITIES Intermediate Liabilities 270,000 $ 120,000 $ 45,000 $ 11,000 $ 4,000 45,000 11,000 4,000 750,000 $ 395,000 $ Machinery & equipment loans (principal due beyond 12 months) Life insurance policy loan Deferred tax liability on: Machinery Breeding stock Long-Term Liabilities Real estate and building loans (principal due beyond 12 months) Deferred tax liability on: real estate and buildings $ $ 40,000 10,000 40,000 10,000 49,500 15,000 $ 190,000 190,000 95,700 65,000 $ 640,000 $ 775,000 1,080,000 1,299,000 Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum Total Non-Current Liabilities $ 240,000 400,200 Total Liabilities $ 358,000 562,090 Owner's Equity $ 417,000 736,910 Total Liabilities + Owner's Equity $ 775,000 1,299,000 9 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Cash to Accrual Analysis Case Example In the case of Ted Greene, the Schedule F shows net cash income of $49,500. Ted generated $4,000 from proceeds from the sale of culled breeding livestock that was not reported on the Schedule F. Please note that the figure is based upon normal culling procedures as any deviation could distort a particular year’s income. Next, an adjustment is made for livestock and crop inventory. The cost basis figures are used in this analysis; however, in both categories, the ending balance sheet for Year YY shows a $5,000 decrease in livestock and $5,000 decrease in crop inventory. This would equate to a $10,000 reduction in revenue generated for the year (Exhibit 5). This is a result of the sale of inventory, which overstates cash revenue on Schedule F. Further examination of the Big Three finds accounts receivable increased by $1,000 from the beginning to ending balance sheet. This would equate to $1,000 of revenue generated but not received in cash for that year, thus adding to the accrual-adjusted income. Finally, analysis of the accounts payable and rents finds that the Greene’s reduced payables by $3,500 during the year. This improved the net income picture from an accrual basis by $3,500. This is because after being paid, payables show as an expense on Schedule F, therefore overstating the expenses on a cash basis. Breaking down the Minor Two finds both prepaid expenses and investment in growing crops increased by $500 each or $1,000. This is an increased expense on a cash basis statement that increases net income on an accrual basis by $1,000, again because of the overstating of expenses on Schedule F. The other Minor Two adjustment accounts are for the change in accrued expenses. In this case, the increase in accrued expenses and taxes of $2,000 would reduce the net cash income when adjusted on an accrual basis. The final adjustment would reflect the impact of normal capital transactions. The Greene’s sold one acre of land for $5,000 to their son Dwight. They plan to continue this practice for the next five years. Thus, this capital transaction is not abnormal. In this illustration, the difference between cash and accrual income was only $2,500. From the Greene’s Schedule F, net farm income from operations was $49,500 on a cash basis, but $47,000 on an accrual-adjusted basis and $52,000 when the proceeds from the sale of capital assets are included. In practice, it is common to find a much larger difference between cash and accrualadjusted measurers of net farm income, particularly in periods of change in the business. A study done recently by the University of Illinois found the discrepancy could often be in the range of 30 to 70 percent. Practicing lenders have discovered similar results. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 10 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 5: Cash Conversion to Accrual-Adjusted Income for Ted Greene Schedule F Net Cash Farm Income (Profit or Loss) Proceeds from sales of culled breeding livestock* + + Big Three Increase in inventory (livestock & crop) Decrease in inventory (livestock & crop) Increase in accounts receivable Decrease in accounts receivable Increase in accounts/rent payable Decrease in accounts/rent payable + + + Minor Two Increase in prepaid expenses (investment in growing crops, supplies) Decrease in prepaid expenses (investment in growing crops, supplies) Increase in accrued expenses (taxes, interest, etc.) Decrease in accrued expenses (taxes, interest, etc.) + + Year ending 12/31/YY $49,500 $4,000 Accrual-adjusted Net Income from Operations Gain/loss from sale of farm capital assets excluding culled breeding livestock** Accrual-adjusted Net Farm Income ($10,000) $1,000 $3,500 $1,000 ($2,000) $47,000 $5,000 $52,000 *Found on tax form 4797 of income tax return "normal culling practices" ** Normal capital transactions (i.e. machinery, equipment, real estate) *** "+" increases accrual-adjusted net income, "-" reduces accrual-adjusted net income. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 11 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Cash to Accrual Conversion: Test Drive Now let’s see how well you grasp the concept of converting cash statements to accrualadjusted income with a “but what if” scenario utilizing the Greene Case situation. Let’s assume the beginning balance sheet and Schedule F tax statement remain the same. However, analysis of the ending balance sheet finds that crop and feed inventory was $95,000 and accounts receivable was $10,000 for hay sold, but no cash was received. They decided to prepay fertilizer so prepaid expenses now total $10,000. However, the Greene’s accounts payable skyrocketed to $15,000. All other categories remained the same, including proceeds from the sale of breeding livestock and the sale of capital assets. Are you up to the challenge? Utilize the cash conversion to accrual-adjusted income worksheet (Exhibit 6). Analyzing the Big Three we find accrual revenue generated by inventory was an additional $20,000, the difference between beginning and ending inventory. Similar calculations find that the change in accounts receivable had an $8,000 positive impact on revenue. However, the $9,000 increase in accounts payable equates to an increased expense on an accrual basis. Shifting to the Minor Two, the increase in prepaid expenses with the fertilizer purchases is another positive along with the previous increase in investment in crops, which amount to $8,500. The increase in accrued expense, i.e. taxes and interest, remain the same $2,000 which is an expense incurred. If you are correct in your analysis, accrual-adjusted net income from operations is $79,000. Accrual-adjusted net farm income is $84,000. This situation illustrated how a build up of inventory and receivables with adjustments in payables can alter the net income picture of a farm operation that only reports cash basis Schedule F income. In the Greene case study, the difference between cash and accrual-adjusted income is nearly 70 percent, which can have a significant impact on financial and credit analysis. Let’s reinforce the fact that a lender would analyze each area to determine whether the adjustments were due to changes in the amount or valuation of the inventory. Was this a marketing strategy or a planned expansion that necessitated increased storage of crops to feed livestock? On the other hand, is the receivable collectable? Was the prepayment of expenses a strategy to reduce taxes? Is the increase in accounts payable a special six month, nointerest deal or was it because the Greene’s cash flow was challenged? This conversion is just another tool in the agrilender’s toolkit. This quick analysis can be useful in developing questions in a business call with Mr. Greene. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 12 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 6: Cash Conversion to Accrual-Adjusted Income: Test Drive Schedule F Net Cash Farm Income (Profit or Loss) Proceeds from sales of culled breeding livestock* + + Big Three Increase in inventory (livestock & crop) Decrease in inventory (livestock & crop) Increase in accounts receivable Decrease in accounts receivable Increase in accounts/rent payable Decrease in accounts/rent payable + + + Minor Two Increase in prepaid expenses (growing crops, supplies) Decrease in prepaid expenses (growing crops, supplies) Increase in accrued expenses (taxes, interest, etc.) Decrease in accrued expenses (taxes, interest, etc.) + + Accrual-adjusted Net Farm Income from Operations Gain/loss from sale of farm capital assets excluding culled breeding livestock** Accrual-adjusted Net Farm Income Year ending 12/31/YY $49,500 $4,000 Test Drive $49,500 $4,000 $20,000 ($10,000) $1,000 $8,000 ($9,000) $3,500 $1,000 $8,500 ($2,000) ($2,000) $47,000 $79,000 $5,000 $52,000 $5,000 $84,000 *Found on tax form 4797 of income tax return "normal culling practices" ** Normal capital transactions (i.e. machinery, equipment, real estate) *** "+" increases accrual-adjusted net income, "-" reduces accrual-adjusted net income. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 13 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Other Adjustments Lending institutions have historically relied heavily on agricultural producer’s tax forms as the primary source of information on income. Often lending institutions have used only Schedule F as the estimate of net farm income. However, as shown in Exhibits 5 and 6, often net farm income as reported on Schedule F does not agree with the accrual-adjusted income. That is because Schedule F does not include sales of breeding livestock and gains/losses from the disposal of capital assets. Further, Schedule F does not take into account the adjustments needed to arrive at accrualadjusted income. In the example for Ted Greene, the difference between the Schedule F measure of net farm income and accrual-adjusted net farm income is more than $2,500 in the first case, and $34,500 in the test drive case. Because differences of this magnitude are common, Schedule F alone is not considered an accurate and complete measure of profitability for farming operations. Verifying Income Statement Information Verifying the income statement is simpler than verifying information on the balance sheet, because federal tax laws require the filing of income-tax returns. Thus, a cash transaction shown in a cash income statement can be verified by information contained in the income tax return. Expense items can also be verified directly from information contained in the income tax return. Accrual adjustments can be verified by examining the beginning and ending balance sheets. Generally speaking, farm expenses are more consistent, while income will vary from year to year, depending upon the producer’s tax and marketing strategies. In some cases, agrilenders are requesting the IRS to provide copies of what was filed rather than rely on the borrower to provide copies because of fraudulent activities. If credit decisions are based on fraudulent information, the lender can incur significant losses and spend a great deal of time in court to recoup monies loaned. If income tax returns are unavailable, verification is more difficult. If the borrower refuses to share income tax returns, the lender should not assume that the income statement actually presented is inaccurate. However, such a situation should concern the lender, because failing to provide such information could be due to failure to file income tax forms or significantly underreported income on the tax form. Whatever the case, the lender may not wish to deal with an individual or business that has failed to establish sound and ethical business practices. As shown in the next section, a statement of owner equity also can be used to help verify information reported on the income statement. Statement of Owner Equity As previously mentioned, a fundamental accounting relationship links a beginning and ending balance sheet to the income statement for that period of time. This relationship is most commonly expressed in the statement of owner equity. This statement relies heavily on information contained in the cost basis balance sheet and the accrualadjusted income statement. A detailed Statement of Owner Equity allows one to Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 14 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity differentiate between what portion of equity is generated as earned net worth as opposed to capital appreciation. The following illustration is an example of the simple version of the statement of owner equity. Beginning cost-basis equity is $425,500, found on Exhibit 3. The balance sheet and income statement do not directly reveal the amount of gifts and inheritances made or received; but in most cases the borrower knows the information, and it can be obtained with few questions by the lender. Net income on an accrual-adjusted basis was $52,000, as shown in the conversion statement in Exhibit 5. Income tax and Social Security payments for the year are $14,500. Net income from the farm business of $52,000, minus $14,500 income tax and Social Security payments equals $37,500. Jeanette’s part-time position as school accountant contributes gross non-farm earnings of $25,000. Owner withdrawals are unknown in this example, but ending owner equity of $417,000 is known from the ending balance sheet (Exhibit 4). Given this information, the lender can easily compute the amount of owner withdrawals: Quick and Easy Statement of Owner Equity If no gifts or inheritances are paid or received, only four items make up the statement of owner equity: beginning owner equity, net income (farm and non-farm), owner withdrawals, and ending owner equity. For example: Beginning Cost-basis Equity, plus Net Income After Taxes, plus Non-farm Income, minus Ending Cost-basis Equity, equals Owner Withdrawals. $425,500 + $37,500 + $25,000 - $417,000 = $71,000 Statement of Owner Equity Case Analysis (Deluxe Version) A detailed version of the statement of owner equity is illustrated in Exhibit 7. This statement allows an agrilender to calculate family living withdrawals and changes in net worth due to earnings or capital asset appreciation. Let’s walk through the Greene’s situation to show how this statement can be used as an analytical tool in credit analysis. Line A finds beginning net worth cost basis $425,500 and market value $692,445. Accrual-adjusted net farm income was $52,000. Estimated income and self-employment tax was calculated to be $14,500 with a net farm after tax income, line D, of $37,500. Withdrawals in total were $71,000, line E; however, $25,000 of non-farm income was contributed toward these uses. The owner’s withdrawal from the business was $46,000, Line G. There were no gifts or inheritance. Thus, the Greene’s living withdrawals cause earned net worth or retained capital, line J, to decline by $8,500, which resulted in an ending net worth on the cost basis of $417,000. When one analyzes market value figures, a different ending owner equity results. In this example, three assets – marketable securities, machinery and real estate – have differences between their cost basis and their market value. The combined differences Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 15 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity between market value and cost basis of these assets totaled $81,000, shown on line K. (Beginning and ending figures for each account are calculated as market value minus cost.) The deferred taxes calculated with new valuation and other changes during the year finds an increase of $28,035, shown on line L. Thus, the change in valuation equity is $52,965, line K less line L, and the ending market value net worth on the balance sheet is $736,910. This single analysis finds that the gain in market value net worth is due to valuation adjustments since earned net worth is actually negative. One would question whether living withdrawals will exceed net after tax income for an extended period or whether it is a one-time abnormality. Hopefully you have developed an appreciation for the linkages of the balance sheet, income statement and statement of owner equity in enriching the value of information and subsequent credit analysis. A few adjustments on the income statement, followed by validation of equity changes through the statement of owner equity can provide tremendous insight into commercial agricultural borrowers’ management strategies, motivations and practices. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 16 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Exhibit 7: Ted Greene (Farm Business Only) Statement of Owner Equity (Deluxe Version) For the Period January 1, YY through December 31, YY Cost Market $425,500 $692,445 A. B. C. Owner Equity, Beginning of Period Net Farm Income Less: Income and S.S. Taxes D. Net Farm Income, After Taxes (B - C) E. F. Withdrawals for Unpaid Labor & Mgmt. Non-Farm Income Contributed to the Farm Business G. H. I. Owner Withdrawals (Net) (F - E) Other Capital Less: Other Capital Distributions/Gifts J. Additions and Reductions in Retained Capital (D + G + H - I) K. Change in Difference between Market Value and Cost/Tax Basis Marketable Sec. Mach. & Equip. Real Estate & Bldg. TOTAL L. N. 37,500 $71,000 25,000 -46,000 0 0 -8,500 -8,500 N/A 52,965 81,000 Ending* Beginning* Change** 9,000 8,000 1,000 150,000 130,000 20,000 290,000 230,000 60,000 449,000 368,000 81,000 Less: Increase in Deferred Taxes & Current Assets Machinery Breeding Livestock Retirement Account Real Estate & Bldg. TOTAL M. $52,000 14,500 28,035 Beginning Change** Ending 43,890 44,055 -165 49,500 42,900 6,600 15,000 13,200 1,800 0 0 0 75,900 19,800 95,700 204,090 176,055 28,035 Total Change in Valuation Equity (K - L for Market Only) Owner Equity, End of Period (A + J + M) $417,000 $736,910 * Market Value minus Cost for each account. ** Ending Value minus Beginning Values for each account. Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 17 CAL Module 2: The Income Statement and Statement of Owner Equity Special Thanks to our Content Reviewers for this Module: • Dr. Freddie Barnard, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN • David Walker, Farm Credit of the Virginias, Staunton, VA • Bill Henley, Colonial Farm Credit, Hughesville, MD Commercial Ag Lending Curriculum 18