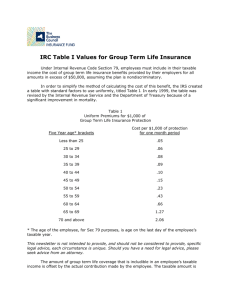

INCOME TAX PLANNING FOR TRUSTS

advertisement