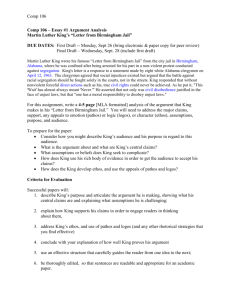

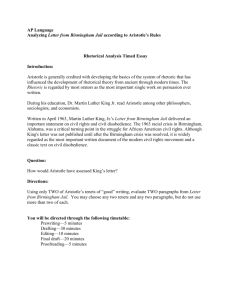

The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama

advertisement

The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama intact, it must make for an equilibrium in society which is increasingly more human in character. 38. But such an order—universal, absolute and immutable in its principles—finds its source in the true, personal and transcendent God. He is the first truth, the sovereign good, and as such the deepest source from which human society, if it is to be properly constituted, creative, and worthy of man’s dignity, draws its genuine vitality. This is what St. Thomas means when he says: Human reason is the standard which measures the degree of goodness of the human will, and as such it derives from the eternal law, which is divine reason . . . Hence it is clear that the goodness of the human will depends much more on the eternal law than on human reason. Characteristics of the Present Day 39. There are three things which characterize our modern age. 40. In the first place we notice a progressive improvement in the economic and social condition of working men. They began by claiming their rights principally in the economic and social spheres, and then proceeded to lay claim to their political rights as well. Finally, they have turned their attention to acquiring the more cultural benefits of society. Today, therefore, working men all over the world are loud in their demands that they shall in no circumstances be subjected to arbitrary treatment, as though devoid of intelligence and freedom. They insist on being treated as human beings, with a share in every sector of human society: in the socioeconomic sphere, in government, and in the realm of learning and culture. 41. Secondly, the part that women are now playing in political life is everywhere evident. This is a development that is perhaps of swifter growth among Christian nations, but it is also happening extensively, if more slowly, among nations that are heirs to different traditions and imbued with a different culture. Women are gaining an increasing awareness of their natural dignity. Far from being content with a purely passive role or allowing themselves to be regarded as a kind of instrument, they are demanding both in domestic and in public life the rights and duties which belong to them as human persons. 42. Finally, we are confronted in this modern age with a form of society which is evolving on entirely new social and political lines. Since all peoples have 496 ■ Religion either attained political independence or are on the way to attaining it, soon no nation will rule over another and none will be subject to an alien power. 43. Thus all over the world men are either the citizens of an independent State, or are shortly to become so; nor is any nation nowadays content to submit to foreign domination. The longstanding inferiority complex of certain classes because of their economic and social status, sex, or position in the State, and the corresponding superiority complex of other classes, is rapidly becoming a thing of the past. . . . Further Resources BOOKS Cahill, Thomas. Pope John XXIII. New York: Viking, 2002. Feldman, Christian. Pope John XXIII: A Spiritual Biography. New York: Crossroad, 2000. Johnson, Paul. Pope John XXIII. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974. PERIODICALS “Jewish Group Wants Pope John XXIII Declared Righteous.” America, September 23, 2000, 5. McBrien, Richard P. “Peasant Profundis.” America, April 8, 2002, 23. Twomey, Gerald S. “Anniversary Thoughts: Ten Lessons from Good Pope John.” America, October 7, 2002, 12. WEBSITES O’Grady, Desmond. “Almost a Saint: Pope John XXIII.” St. Anthony Messenger. Available online at http://www.american catholic.org/Messenger/Nov1996/feature1.asp; website home page: http://www.americancatholic.org/default.asp (acessed February 2, 2003). Randall, Beth. “Illuminating Lives: Pope John XXIII.” Available online at http://www.mcs.drexel.edu/~gbrandal/Illum _html/JohnXXIII.html (accessed February 2, 2003). The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama “Public Statement by Eight Alabama Clergymen” Statement By: C.C.J. Carpenter, Joseph A. Durick, Milton L. Grafman, Paul Hardin, Nolan B. Harmon, George M. Murray, Edward V. Ramage, and Earl Stallings Date: April 12, 1963 Source: Carpenter, C.C.J., et al. “Public Statement by Eight Alabama Clergymen.” Birmingham News, April 12, 1963. American Decades Primary Sources, 1960 –1969 The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama About the Authors: The eight Alabama clergymen represented a wide spectrum of religions, including priests, bishops, ministers, and a rabbi from the Episcopalian, Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Jewish faiths. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” Letter By: Martin Luther King Jr. Date: April 16, 1963 Source: King, Martin Luther, Jr. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” April 16, 1963. Available online at http://www .mlkonline.com/jail.html (accessed February 2, 2003). About the Author: Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968), born in Atlanta, was ordained a Baptist minister in 1954 and received his doctorate from Boston University in 1955. Instrumental in the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957, he advocated nonviolence in the Civil Rights movement. He served as a major organizer of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956 and the March on Washington in 1963. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, but four years later he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. ■ Introduction In the spring of 1963, during a peaceful civil rights march in downtown Birmingham, Alabama, Martin Luther King Jr. found himself in a confrontation with “Bull” Connor and other city authorities. T. Eugene “Bull” Connor (1897–1973) was the commissioner of public safety in Birmingham and a leader of the city’s segregationist forces. King, the leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was in Birmingham to oppose racial segregation. As a result of this confrontation, King was arrested and jailed. At the time of the protest, Birmingham was one of the most industrialized cities in the South. With a population of about 40 percent African Americans, it was also one of the nation’s most segregated cities. Two years earlier, in 1961, civil rights freedom riders—African Americans and whites who entered southern cities by bus to test the local reaction to integrated seating on that bus— had been violently attacked in Alabama. Also, Birmingham and other southern cities had been the scenes of bombings directed at African Americans and civil rights protesters. On April 12, 1963, a group of eight Alabama clergymen issued a “Public Statement by Eight Alabama Clergymen,” appealing to the African American community “to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham.” The clergymen supported the goals of the Civil Rights movement but opposed the tactics being employed in Birmingham. They feared that further demonstrations by King and his followers would worsen race American Decades Primary Sources, 1960 –1969 relations and result in deadly violence. Four days later, while in jail, King responded to this statement in a letter to his fellow clergymen explaining why he helped organize and participate in the protests. That letter, dated April 16, 1963, was the now famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Significance “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” received international as well as national attention and has been reprinted throughout the world in newspapers, magazines, and books. The demonstrations had clearly affected many people beyond Alabama and the United States. For weeks, events in Birmingham had been a leading news item, and pictures of dogs attacking protesters and demonstrators being drenched by fire hoses were seen worldwide. King was released after serving eight days in jail, but he continued leading massive civil rights demonstrations. Rallies were held in several African American churches for sixty-five consecutive nights, and during the day directaction protests were conducted. By the end of the first week in May 1963, two thousand protesters had been arrested. On May 10, 1963, a desegregation agreement affecting lunch counters, drinking fountains, and other facilities was reached and the demonstrations stopped. A permanent biracial committee was organized, demonstrators were released from jail, and more hiring of African Americans in clerical jobs was promised. It would take time for social change to take place in Birmingham and racial healing to occur. Almost forty years after these confrontations, though, the city takes pride in its Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. The institute describes itself as “a place of remembrance, revolution and reconciliation built at the site of the most tumultuous events of the Civil Rights era. More than a museum, it also serves as a forum for understanding the universal problem of racism—while chronicling the role Birmingham played in setting a people free.” Primary Source “Public Statement by Eight Alabama Clergymen” In response to civil rights protests in Birmingham, eight Alabama clergymen composed a statement urging restraint in the Civil Rights movement and the discontinuance of demonstrations in Birmingham. The authors explained that progress could best be achieved through negotiation and through the court system and suggested that direct action would only make the situation worse. SYNOPSIS: We the undersigned clergymen are among those who, in January, issued “An Appeal for Law and Religion ■ 497 The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama Order and Common Sense,” in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. We expressed understanding that honest convictions in racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts, but urged that decisions of those courts should in the meantime be peacefully obeyed. Since that time there had been some evidence of increased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Responsible citizens have undertaken to work on various problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Birmingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and realistic approach to racial problems. However, we are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely. We agree rather with certain local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area. And we believe this kind of facing of issues can best be accomplished by citizens of our own metropolitan area, white and Negro, meeting with their knowledge and experience of the local situation. All of us need to face that responsibility and find proper channels for its accomplishment. Just as we formerly pointed out that “hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions,” we also point out that such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems. We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham. We commend the community as a whole, and the local news media and law enforcement in particular, on the calm manner in which these demonstrations have been handled. We urge the public to continue to show restraint should the demonstrations continue, and the law enforcement official to remain calm and continue to protect our city from violence. We further strongly urge our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham. When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and 498 ■ Religion in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets. We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense. Bishop C.C.J. Carpenter, D.D., LL.D., Episcopalian Bishop of Alabama Bishop Joseph A. Durick, D.D., Auxiliary Bishop, Roman Catholic Diocese of Mobile, Birmingham Rabbi Milton L. Grafman, Temple Emanu-El, Birmingham, Alabama Bishop Paul Hardin, Methodist Bishop of the AlabamaWest Florida Conference Bishop Nolan B. Harmon, Bishop of the North Alabama Conference of the Methodist Church Rev. George M. Murray, D.D., LL.D, Bishop Coadjutor, Episcopal Diocese of Alabama Rev. Edward V. Ramage, Moderator, Synod of the Alabama Presbyterian Church in the United States Rev. Earl Stallings, Pastor, First Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama Primary Source “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” [excerpt] In response to this statement, Martin Luther King Jr. composed his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to explain why he was active in civil rights demonstrations—primarily the failure of the courts and negotiation to address effectively the issue of civil rights. SYNOPSIS: My Dear Fellow Clergymen: While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms. I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in.” I have the honor of serving as President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization operating in every southern state, with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. We have some eighty-five affiliated organizations across the South, and one of them is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Frequently we share staff, educational and financial resources with our affiliates. Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call American Decades Primary Sources, 1960 –1969 The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama Civil rights protesters kneel on a sidewalk after being arrested for parading without a permit, Birmingham, Alabama, May 2, 1963. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. supported nonviolent civil disobedience and demonstrations to effect change in American society. © B E T T M A N N / C O R B I S . REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION. to engage in a nonviolent direct-action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here. But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid. Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in American Decades Primary Sources, 1960 –1969 Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds. You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative. Religion ■ 499 The Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama On the basis of these promises, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the leaders of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights agreed to a moratorium on all demonstrations. As the weeks and months went by, we realized that we were the victims of a broken promise. A few signs, briefly removed, returned; the others remained. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stares out the window of his cell in the Jefferson County Courthouse, Birmingham, Alabama. Four days after local religious leaders urged restraint in the Civil Rights movement, King responded to this criticism in his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” © B E T T M A N N / C O R B I S . R E P R O D U C E D B Y P E R M I S S I O N . In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gain saying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham that [sic] in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in goodfaith negotiation. Then, last September, came the opportunity to talk with leaders of Birmingham’s economic community. In the course of the negotiations, certain promises were made by the merchants—for example, to remove the stores’ humiliating racial signs. 500 ■ Religion As in so many past experiences, our hopes had been blasted, and the shadow of deep disappointment settled upon us. We had no alternative except to prepare for direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community. Mindful of the difficulties involved, we decided to undertake a process of self-purification. We began a series of workshops on nonviolence, and we repeatedly asked ourselves: “Are you able to accept blows without retaliation?” “are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?” We decided to schedule our direct-action program for the Easter season, realizing that except for Christmas, this is the main shopping period of the year. Knowing that a strong economic withdrawal program would be the by-product of direct action, we felt that this would be the best time to bring pressure to bear on the merchants for the needed change. Then it occurred to us that Birmingham’s mayoralty election was coming up in March, and we speedily decided to postpone action until after election day. When we discovered that the Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene “Bill” Connor, had piled up enough votes to be in the run-off, we decided again to postpone action until the day after the run-off so that the demonstrations could not be used to cloud the issues. Like many others, we waited to see Mr. Connor defeated, and to this end we endured postponement after postponement. Having aided in this community need, we felt that our direct-action program could be delayed no longer. You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sitins, marches, and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent-resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent American Decades Primary Sources, 1960 –1969 “Eulogy for the Martyred Children” tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue. One of the basic points in your statement is that the action that I and my associates have taken in Birmingham is untimely. Some have asked: “Why didn’t you give the new city administration time to act?” The only answer that I can give to this query is that the new Birmingham administration must be prodded about as much as the outgoing one, before it will act. We are sadly mistaken if we feel that the election of Albert Boutwell as mayor will bring the millennium to Birmingham. While Mr. Boutwell is a much more gentle person that Mr. Connor, they are both segregationists, dedicated to maintenance of the status quo. I have hoped that Mr. Boutwell will be reasonable enough to see the futility of massive resistance to desegregation. But he will not see this without pressure from devotees of civil rights. My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals. We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor, it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct-action campaign that was “well timed” in view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.” . . . American Decades Primary Sources, 1960 –1969 Further Resources BOOKS Blaustein, Albert P., and Robert L. Zangrando, eds. Civil Rights and the American Negro: A Documentary History. New York: Washington Square Press, 1968. Dunn, John M. The Civil Rights Movement. New York: Lucent Books, 1998. Higham, John, ed. Civil Rights and Social Wrongs: Black-White Relations Since World War II. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997. PERIODICALS Harris, William. “The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Volume IV: Symbol of the Movement, January 1957–December 1958.” Journal of Southern History, August 2002, 750. McDonald, Dora. “Sharing the Dream: Martin Luther King Jr., the Movement, and Me.” Library Journal, November 1, 2002, 110. Walton, Anthony. “A Dream Deferred: Why Martin Luther King Has Yet to Be Heard.” Harper’s, August 2002, 67. WEBSITES National Civil Rights Museum home page. Available online at http://www.civilrightsmuseum.org/ (accessed February 2, 2003). U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division home page. Available online at http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/crt-home.html (accessed February 2, 2003). Western Michigan University Department of Political Science. “Timeline of the American Civil Rights Movement.” Available online at http://www.wmich.edu/politics/mlk/ (accessed February 2, 2003). This site contains links to articles on key events in the Civil Rights movement. “Eulogy for the Martyred Children” Eulogy By: Martin Luther King Jr. Date: September 18, 1963 Source: King, Martin Luther, Jr. “Eulogy for the Martyred Children.” Delivered at Sixth Avenue Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama, September 18, 1963. Available online at http://www.mlkonline.com/eulogy.html (accessed February 2, 2003). About the Author: Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968), born in Atlanta, Georgia, was ordained a Baptist minister in 1954 and received his doctorate from Boston University in 1955. Instrumental in the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957, he advocated nonviolence in the Civil Rights movement. He served as a major organizer of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956 and the March on Washington in 1963. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, but four years later he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. ■ Religion ■ 501