Hamlet: Violence in Act III, Scene 4 Analysis

advertisement

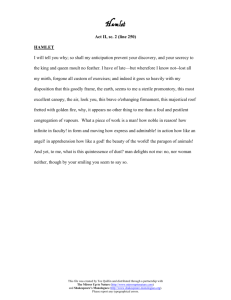

Charles W. Johnson AP English - Rygiel 16 December 1998 The Use of Violence in Shakespeare’s Hamlet In great literature, every action reinforces the underlying truth of the work’s Universe. No action should exist for its own sake; it must advance the machine of the plot and reinforce the symbolic meaning of the work. This is especially true of acts of violence; great literature must carefully incorporate the violence into a coherent meaning, or else we have nothing more than a glorified action movie. The violence of act III, scene 4 of Hamlet--in which Prince Hamlet of Denmark confronts his mother and kills Polonius--is a prime example of bloodshed serving to illuminate important aspects of the story. Scene four sets the play into motion, permanently altering Hamlet’s thoughts and actions, as well as other characters’ treatment of him. The scene also illustrates key themes of the play: the price of our actions, the gap between appearences and reality, and Hamlet’s progression from brooding overanalysis to swift action. By accentuating the themes and forcing the plot into motion, the violence of 3.4 adds greatly to the meaning of the work as a whole. The scene begins in Queen Gertrude’s room as Polonius hides behind a tapestry-establishing a conflict between the appearance of privacy and the reality that Polonius is spying on the conversation. When Hamlet arrives, he verbally and physically confronts his mother, shouting “Come, come, and sit you down; you shall not budge./You go not till I set up a glass/Where you may see the inmost part of you” (3.4.23-25). The Queen is so alarmed by Hamlet’s hostility that she fears for her life, and cries out “Thou wilt not murder me? Help ho!” (3.4.26). Hearing her, Polonius confusedly yells back. Hamlet, thinking that the unseen spy is the King (thus acting on appearence rather than reality), blindly strikes out at the arras, killing Polonius. The price of being the “wretched, rash, intruding fool” (3.4.37) is Polonius’s own life. The scene poses another question of appearences and reality by casting doubt as to whether Hamlet is still “mad in craft” (3.4.210), or whether he has indeed lost his mind. Hamlet expresses no guilt for the deaths of three innocents: Polonius in 3.4, and later, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Appearances and reality are brought to the front again as his mother cries out, “What rash and bloody deed is this!” (3.4.33), only for Hamlet to fire back without remorse: “A bloody deed--almost as bad, good mother,/As to kill a king and marry his brother” (3.4.35), as though to redirect the guilt away from Hamlet, the apparent man at fault, to older crime of the Queen herself. The scene no longer centers on the death of Polonius, but rather on the larger arc of Hamlet’s obsession and resentment towards his mother for betraying him and his father by the quick and convenient marriage to Claudius. The scene is also crucial to the progression of the plot and Hamlet’s character as well. Previously, the Prince was hesitant to act. He was unsure of whether to believe the ghost. His fear of “what dreams may come” (3.1.74) after death prevents him from killing himself. In the previous scene, Hamlet had the chance to kill King Claudius, but backed down when he saw that the King was praying, on the excuse that killing Claudius then would send him to heaven. When Hamlet hears the spy in scene four however, he lashes out violently. None of the careful analysis is given to the consequences, as was given to all his other actions. Hamlet does not even stop to ponder who the person behind the tapestry might be, or why he might be there. Although he may think that it is the King, it is clear that Hamlet is more interested in lashing out at someone, anyone, than in killing the King per se. This lashing out serves as the pivot point for the entire play. Until now, the actions of the play have all been to set up the elaborate and fatal machine of the plot. Hamlet has only brooded and pondered; he has taken almost no action whatsoever, despite many opportunities. This scene acts as the first critical motion, which disturbs the system and sets events into their ultimate course. After Hamlet kills Polonius, an important member of the court, he cannot turn back. He cannot afford to stop and overanalyze everything any longer; if he stops to brood over what he has done, then he will be destroyed--if not by the King then by his own guilt. Polonius’s death also has great consequences for the actions of others. Ophelia goes mad and commits suicide after hearing of her father’s death. Claudius begins to fear Hamlet, and so starts to plot against his nephew. The deaths of both his father Polonius and his sister Ophelia move Laertes to hatred of Hamlet, his former friend, and thus Laertes becomes an instrument of Claudius’s schemes. As a result of Hamlet’s rash action and Claudius’s schemes, Hamlet and Laertes are poisoned in their swordfight, the Queen drinks to her death, and Hamlet kills Claudius with the very poison that Claudius intended for Hamlet. The violence in 3.4 does not exist simply to add a pointless action scene to the play. Hamlet’s “rash and bloody deed” (3.4.33) propels the entire play toward its bloody finale. The actions of Hamlet and Gertrude underscore many of the underlying themes. The scene also further fleshes out the characters of Hamlet and the Queen, their intentions, and their actions. Thus, the dark violence of scene four serves to illuminate the work as a whole.