Lesson Overview

advertisement

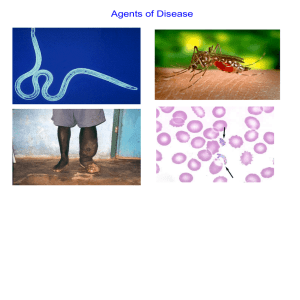

Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lesson Overview 20.1 Viruses Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome THINK ABOUT IT Imagine that farmers have begun to lose their tobacco crop to a plant disease. To determine what is causing the disease, you take leaves from a diseased plant and crush them to produce a liquid extract. The liquid contains disease-causing agents so small that they are not visible under a microscope and can pass right through a filter. What would you do next? How would you deal with the invisible? Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome The Discovery of Viruses How do viruses reproduce? Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome The Discovery of Viruses How do viruses reproduce? Viruses can reproduce only by infecting living cells. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Discovery of Viruses In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovski demonstrated that the cause of tobacco mosaic disease was found in the liquid extracted from infected plants. In 1897, Martinus Beijerinck suggested that tiny particles in the juice caused the disease, and he named these particles viruses, after the Latin word for “poison.” In 1935, Wendell Stanley isolated crystals of tobacco mosaic virus. Since living organisms do not crystallize, Stanley inferred that viruses were not truly alive. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Discovery of Viruses A virus is a nonliving particle made of proteins, nucleic acids, and sometimes lipids. Viruses can reproduce only by infecting living cells. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Structure and Composition Viruses differ widely in terms of size and structure. Most viruses are so small they can be seen only with the aid of a powerful electron microscope. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Structure and Composition The protein coat surrounding a virus is called a capsid. Some viruses, such as the influenza virus, have an additional membrane that surrounds the capsid. The simplest viruses contain only a few genes, whereas the most complex may have more than a hundred genes. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Structure and Composition Most viruses have proteins on their surface membrane or capsid that bind to receptor proteins on the host cell. The proteins “trick” the cell to take the virus, or in some cases just its genetic material, into the cell. Once inside, the viral genes are eventually expressed and may destroy the cell. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Structure and Composition Most viruses infect only a very specific kind of cell. Plant viruses infect plant cells; most animal viruses infect only certain related species of animals; viruses that infect bacteria are called bacteriophages. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Viral Infections What happens after a virus infects a cell? Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Viral Infections What happens after a virus infects a cell? Inside living cells, viruses use their genetic information to make multiple copies of themselves. Some viruses replicate immediately, while others initially persist in an inactive state within the host. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections In a lytic infection, a virus enters a bacterial cell, makes copies of itself, and causes the cell to burst, or lyse. Bacteriophage T4 is an example of a bacteriophage that causes such an infection. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections Bacteriophage T4 has a DNA core inside a protein capsid that binds to the surface of a host cell. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections The virus injects its DNA into the cell. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections The cell then begins to make messenger RNA (mRNA) from the viral genes. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections The viral mRNA is translated into viral proteins that chop up the cell’s DNA. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections Controlled by viral genes, the host cell’s metabolic system makes copies of viral nucleic acid. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections The host cell’s metabolic system also makes copies of capsid proteins. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections The viral nucleic acid and capsid proteins are then assembled into new virus particles. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections The host cell lyses, releasing hundreds of virus particles that go on to infect other cells. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections A lytic virus is similar to an outlaw in the Wild West of the American frontier in the demands the virus makes on its host. First, the outlaw eliminates the town’s existing authority. In a lytic infection, the host cell’s DNA is chopped up. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections Next, the outlaw demands to be outfitted with new equipment from the local townspeople. In a lytic infection, the viruses use the host cell to make viral DNA and viral proteins. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lytic Infections Finally, the outlaw forms a gang that leaves the town to attack new communities. In a lytic infection, the host cell bursts, releasing hundreds of virus particles. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection Some bacterial viruses cause a lysogenic infection. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection In a lysogenic infection a host cell is not immediately taken over. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection The viral nucleic acid is inserted into the host cell’s DNA. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection The viral DNA is then copied along with the host DNA without damaging the host. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection Viral DNA multiplies as the host cells multiply. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection In this way, each generation of daughter cells derived from the original host cell is infected. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection Bacteriophage DNA that becomes embedded in the bacterial host’s DNA is called a prophage. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection The prophage may remain part of the DNA of the host cell for many generations. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection Influences from the environment—radiation, heat, etc—trigger the prophage to become active. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Lysogenic Infection It then removes itself from the host cell DNA, directs the synthesis of new virus particles, and now becomes an active lytic infection. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome A Closer Look at Two RNA Viruses About 70 percent of viruses contain RNA rather than DNA. In humans, RNA viruses cause a wide range of infections, from relatively mild colds to severe cases of HIV. Certain kinds of cancer also begin with an infection by viral RNA. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome The Common Cold Cold viruses attack with a very simple, fast-acting infection. A capsid settles on a cell, typically in the host’s nose, and is brought inside, where a viral protein makes many new copies of the viral RNA. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome The Common Cold The host cell’s ribosomes mistake the viral RNA for the host’s own mRNA and translate it into capsids and other viral proteins. The new capsids assemble around the viral RNA copies, and within 8 hours, the host cell releases hundreds of new virus particles to infect other cells. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome HIV The deadly disease called acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is caused by an RNA virus called human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV belongs to a group of RNA viruses that are called retroviruses. The genetic information of a retrovirus is copied from RNA to DNA instead of from DNA to RNA. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome HIV When a retrovirus infects a cell, it makes a DNA copy of its RNA. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome HIV The copy inserts itself into the DNA of the host cell. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome HIV Retroviral infections are similar to lysogenic infections of bacteria. Much like a prophage in a bacterial host, the viral DNA may remain inactive for many cell cycles before making new virus particles and damaging the cells of the host’s immune system. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Viruses and Cells All viruses are parasites. Parasites depend entirely upon other living organisms for their existence, harming these organisms in the process. Viruses must infect living cells in order to grow and reproduce, taking advantage of the nutrients and cellular machinery of their hosts. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Viruses and Cells Viruses have many of the characteristics of living things. After infecting living cells, viruses can reproduce, regulate gene expression, and even evolve. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Viruses and Cells Some of the main differences between cells and viruses are summarized in this chart. Lesson Overview Studying the Human Genome Viruses and Cells Although viruses are smaller and simpler than the smallest cells, it is unlikely that they were the first living organisms. Because viruses are dependent upon living organisms, it seems more likely that viruses developed after living cells. The first viruses may have evolved from the genetic material of living cells. Viruses have continued to evolve, along with the cells they infect, for billions of years.