Relationship as a Path to Integrity, Wisdom, and Meaning

advertisement

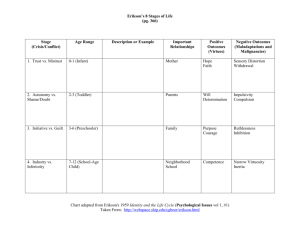

Relationship as a Path to Integrity, Wisdom, and Meaning By Ruthellen Josselson, The Fielding Institute and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem How deeply worried self-made man is in his need to feel safe in his man-made world, can be seen from the deep inroad which an unconscious identification with the machine…has made on the Western concept of human nature…The desperate need to function smoothly and cleanly, without friction, sputtering, or smoke, has attached itself to the ideas of personal happiness, of governmental perfection, and even of salvation.” (Erikson, 1968, p.84) What is it that adult women learn that leads them to a sense of integrity and wisdom at midlife? How are we social scientists equipped to study that process? Of the final stage of his epigenetic model of human development, “Integrity vs. Despair,” Erik Erikson (1950) had this to say: “Only in him who in some way has taken care of things and people and has adapted himself to the triumphs and disappointments adherent to being the originator of others or the generator of products and ideas—only in him may gradually ripen the fruit of these seven stages. I know no better word for it than ego integrity” (p. 268). Erikson, however, went on to say that he could not define this sense, but could only point to its markers, which include a sense of world order and spirituality, an acceptance of one’s one-and-only life cycle as something that had to be, and the readiness to defend the dignity of one’s life against all physical and economic threats. Later, he added that the “favorable ratio” derived from the integrity stage is wisdom. Late in his life, Erikson, in collaboration with his wife, Joan, devoted much of his energy to working out the ways in which integrity and despair are balanced at the close of the life cycle (Erikson & Erikson, 1997; Erikson, Erikson, & Kivnick, 1986). Increasingly, they emphasize the accretion of wisdom as the hallmark of this stage. The crisis of integrity versus despair is initiated by the realization that there is not enough time remaining to correct the life course or to realize unfulfilled dreams. Thus, meaning must be sought in reflection. But Erikson’s epigenetic model includes the recognition that each life stage has precursors in the ones before as “the individual is increasingly engaged in the anticipation of tensions that have yet to become focal (1986, p. 39)”. This would imply that a reaching for integrity (and a concomitant escape from despair) is in the shadows of each of the earlier stages and becomes more prominent in its influence as one draws closer to death. 1 From the identity stage onwards, each new stage has as a subtext issues of integrity and wisdom, phrased differently and of different import in each psychosocial crisis. Identity, for example, the hallmark of the late adolescent phase, always has as its subtext a sense of meaningfulness. “What might I do or be that would matter in this life?” wonders the young person. “How can I join the world as I find it in a way that would feel meaningful?” Similarly, in the generativity stage, the adult makes efforts to invest his or her efforts in products, be they children or projects, which would offer to the world something that seems meaningful. Particularly at midlife, the adult wonders, “Is this a worthwhile way to be spending my time?” Generativity is the effort to do something productive (Bradley & Marcia, 1998; Bradley, 1997; McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1998). Integrity is the sense that what one is doing has larger meaning. Elsewhere I have asserted that for women development of the identity and intimacy stages appears to be conflated (Josselson, 1978). The sense of meaningful engagement in the world—who one is—is inextricably tangled with the sense of meaningful connection to others—not just spouse and children, but also parents, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and those to whom her work is devoted—patients, students, clients. Similarly, the experience of generativity is also bound up with the experience of intimacy: what a woman produces is interwoven with her sense of connection to those to whom her efforts are directed. I intend to explore how the sense of integrity, wisdom, and hence meaning, develops on a path of intimacy and relatedness in American women at midlife. Traditional concepts of wisdom lead to abstract principles and disembodied ideals (Chandler & Holliday, 1990), far from the pulse of emotional knowledge, far from the interpersonal insight that women hold dear. The Eriksons, however, tracing the roots of the words integrity and wisdom, locate them in the earthbound strengths of seeing, knowing, and touching. “It is in actuality that we live and move and share the earth with one another. Without contact there is no growth (Erikson, & Erikson, 1997, p.8)” The contemporary American woman, embedded in a culture that both valorizes and denigrates relatedness, does not simply “have” relationships, but invests them with her spirit (Miller, 1999), grows through them, and derives her sense of meaningfulness from them. The sense of connection to what is larger than the self is experienced in relational terms (see also Miller, 1976; Jordan, 1986; Ballou, 1995). The intersection of relationship and wisdom for women is to be found in two separate but related processes: deepening the understanding of relationships and enlarging the meaning of care. Before exploring these processes, however, I want to first reflect on how we, as social scientists, can learn about others’ meaning-making. The Study of Meaning-Making Meaning-making relies on forms of knowing that are not easily captured in linear representation. Such understanding is experienced as an inner knowledge, an awareness of insight, an enlargement of the sense of self; because of its affective and intuitive base, it is often difficult to express in language. Labouvie-Vief (1990) asserts 2 that adult development and wisdom consist of integrating what she terms logos, or rational thought, with mythos, an inner, subjective sense of union with some larger principle. In mythos, “truth is psychological rather than logical and validation is by intuitive criteria of ‘felt sense’” (p. 55). While logos can be defined and demonstrated with precision and agreement, mythos refers to what Clinchy (1996) has called connected forms of knowing where knowledge is derived from empathy and intuition as well as consensually validated phenomena. Labouvie-Vief (1990) argues that social pressures of human development privilege logos. The child learns that imagination and inner states have no objective existence and must find ways to suppress these experiences in favor of the workings of the external, conventional world. In other words, the task of development in preadult life is to “fit in” through learning the symbol systems, skills, and value systems of the culture and society in which the young person is growing. But in adulthood, once worldly competence has been reasonably mastered and the claim to identity has been staked, the cognitive and emotional turn is inward, once again valuing the truths of the heart. The integration of the emotions and even irrationality itself lend richness to adult experience and forms the core of adult psychological development. But these forms of development are resistant to research endeavors which are framed in paradigmatic modes (Bruner, 1986) that favor logos in their emphasis on explicit rules, deduction, and prediction. Narrative knowledge, by contrast, privileges human intentionality and meaning-making, finding truth hermeneutically in experience rather than in what is externally verifiable. Surveying contemporary research on wisdom, Robinson (1990) and Birren and Fisher (1990) suggest that the hegemony of the late nineteenth-century scientific method has led to a “Dark Ages” in our knowledge of wisdom, which may only be accessible through phenomenological forms of inquiry. Interview methods are necessary to access mythos and narrative forms of knowing, but even with these it is difficult to transcend the interviewee’s overlearned habits of speaking about their knowledge in terms of logos. Because we live in a culture which so privileges the rational, the demonstrable, and the externally justified, there is a fair amount of shame attached to publicly airing inner states or emotions that lie close to a deeply valued core of self. Even with the most skillful interviewer, people who are interviewed still want to sound “normal,” “healthy,” and acceptable. Thus, those of us who interview others as a way of doing research must learn to read between the words that are spoken for underlying meaning and to hear in emphases on words or snippets of emotion what moves another person, what grounds his or her existence. I was asked to write this chapter because of the long-term research I have done on development in women. Over 22 years, I intensively interviewed a group of 30 women from the time they graduated college in 1970 (Josselson, 1996). Immediately, I felt that I knew how these women construed their path to wisdom and integrity—they did it through their experience of relationship. I “know” this on the basis of mythos, a connected form of knowing that grows out of having known these women deeply over 22 years. In order to write about what I know, however, unless I write a poem, I must translate this knowledge into some logical form in order to share 3 with my readers what it is I believe I know. And then I must try to integrate that logos with other analyses of adult development in a way that does not obliterate the very mythos that is the basis of these women’s meaning-making—and my own. As I review the interviews that I have conducted over all these years, I see that these women have been trying to tell me how they make meaning. But as they do this, they are also trying to translate an inner, complex, emotional process into stark language which often won’t absorb and transmit the hard-won knowledge they so prize. These are not especially spiritual women, at least not in the religious sense— only 2 of the 30 are devoutly religious; most disclaim any but the most superficial religious affiliation. They do not move in communities that offer them a language of transcendent growth, unless one were to count self-help books. Nearly all are employed; half are mothers. Most would be considered either “generative” or “communal” according to the generativity status classification devised by Bradley and Marcia (1998). Leading ordinary lives, they are not exemplars of “wise” people, yet each experiences a growth in wisdom and insight as she ages. Each tries to speak of what she has “seen” and “known,” what she has touched and been touched by, and how she feels part of something larger than herself. The challenge to developmental psychology is to track the growth of the experience of integrity in lives such as these. The Centrality of Relationships When they were 43 years old I asked these 30 women to imagine they were 80 years old and looking back over their lives (inviting them to project themselves into Erikson’s integrity stage). What would they be most satisfied to have accomplished or experienced in their life? I asked this at the end of a 4- to 5-hour interview, when they were tired—yet their answers came easily. Nearly all focused immediately on their relationships: Brenda (married, no children): I would love to leave some kind of eternal legacy, but without any artistic talent, creativity, or inventiveness, I don’t feel that I can leave much behind me except friends who love me, whose life I made more pleasant in some way. Maybe, if I advance in my career I can leave some legacy, but the accomplishment of rising in industry won’t be as satisfying as friendships and love would be. Nancy (married, no children): To look back and feel the relationships I’ve been in have been deep and meaningful and I helped make that happen. Helen (married, two children): I will be satisfied to be married 59 years at that point. I will be proud of my children and of my career. I will be proud of all the students that I was able to help. Leslie (unmarried, no children): I will be satisfied in knowing that I had an opportunity to love someone deeply and be loved back; that my own little corner of the world was better off for my having been there. 4 Regina (married, two children): If my life had to end right now, I would say that I’ve covered all the important bases for myself already. I have friends who I think truly love me, I have maintained good family relationships and I have a husband who really loves me. I have retained the relationship with him through some daunting ups and downs in recent years. I have begun to raise two children who are exuberant and happy. I think I’ve made a genuine difference in some people’s lives—clients who discovered new life directions with my support, students who refer to me as teaching them everything they knew. I’ve had a rich inner life, a life I’ve been able to share with other people from time to time.1 Written on a page or even heard on the tape recorder, these answers sound pat, superficial, hardly wise. They name relational connections, point to roles these women have played with others (mother, wife, teacher, doctor, etc.), but the substance of their experiences are only indicated. What is overlooked when we stop our investigation at the names of these relationships is the work of meaning-making—the struggled-for wisdom and understanding that underlies them. Only by listening carefully and often between the lines of a woman’s interview does the wisdom about relationship emerge. Wisdom in Relationship Until recently, we have understood relationship in terms of social roles. The developmental story of relationship that has dominated our understanding of women is that her fate lies in her choice of a life partner.2 The rise of the novel concretized this construction, giving prominence to the “marriage plot” in which a woman’s destiny is sealed by the man she marries. But we never know what happens after— how she continues to create meaning in her life (Heilbrun, 1988). A woman may be a spouse or partner to one other person, but the question is what kind of partner she will be; a woman may be a mother or a nurturer to the next generation, but she now has many choices about the ways in which she will nurture. Friendship is beginning to receive the recognition it deserves as a source of meaning in adult life and a woman has many different forms of friendship (Apter & Josselson, 1998). Work and career, too, are often experienced and expressed in relational terms (Josselson, 1996). Relationships become the site at which individual identity and social commitment are melded and form the arena of meaning and integrity. If wisdom and integrity are traceable to experience in relationships, just what is it that is “seen” and “known” that we might say are indicative of these attributes? One problem in taking up this question is that the discourse about knowledge in relationships has largely been muted in our individualistic society (Swidler, 1980). A second problem is that knowledge about relationships is not primarily cognitive (although it may have a cognitive component). Rather, it is visceral, empathic, a kind of knowing that fundamentally alters one’s experience of otherness and hence one’s experience of self in the world. 5 Even with interview methods, this experience of insight about relationships is hard to put into language. Grappling for words, Clara, an otherwise highly articulate woman said, “With time, I just understand so much more about people.” Again, we might ask, But what does she understand? In what lies her wisdom? And can we ever hope to get this into psychological language? In late childhood, as friends begin to take on emotional significance beyond companionship, girls grapple with the complexity of being intimate with another person outside the family where relationships are given, structured, and assured. This is the introduction to the problems of bringing oneself to others and taking them in as they are. A friend may be unresponsive, may not understand one’s deeply felt emotions, may betray confidences in ways that shame, or may reject in favor of another friend. The growing girl must learn to come to terms with the tension between what she really feels in relationships and what she learns she must be and how she must act to gain approval3—and therefore connection—from others. How can you say what you think when it may hurt someone else’s feelings and then they may abandon you? But what is friendship if you can’t say what you think? In all these experiences, the growing girl must try to make sense of human unpredictability, of the complexities of trust, and of the difficulties that inevitably accompany being with and relying on others. As she passes into late adolescence, the young woman must again confront these dilemmas as she explores the possibilities for deep intimacy with someone who may be a life partner. Most young women have ideals for intimate relationships. Woman in midlife speak of intimate relationships—and of friendship—differently. They have learned that relationships are difficult processes: People won’t be what you want them to be and being with others is a constant state of rethinking who one is and who they are. Part of what accompanies the experience of wisdom in relationship lies in a growing and changing appreciation of otherness which moves beyond categorization and projection. Development involves learning first to define the self in contrast to others: I am like this, others are like that. With time, however, one becomes reified in these descriptors and begins to question them. I am white, but what does whiteness really mean? I am female, but what is gender? I am caring, but also have my hostile and selfish sides. Adult development involves moving out of those identity categories that one was at such pains to solidify earlier and into a more relativistic position, not just cognitively, but emotionally, recognizing the shared humanity and other shared attributes in all of us. This is perhaps what Jung was trying to elucidate in his concept of individuation. Within psychoanalytic theory, there has been increasing focus on subjectsubject relations as opposed to object relations (Mitchell, 1988; Stolorow & Atwood, 1992). The more problematic and challenging aspects of psychological and emotional development concern the articulation of self with others who are also selves. In this view, the experience of self is intertwined with an intersubjective context that forms, sustains, and allows expression of self. 6 The development of intersubjectivity is a complex matter and brings to the forefront the murky borderland of human interconnection. Others are in part a product of our own construal while we are in part an amalgam of what others have made of us. And yet we must form ongoing relationships with the others who retain a reality independent of our mutual representations and misrepresentations. Buber (1965) suggests that true “I-thou” relations are possible through “making the other present,” through our empathic capacity to “imagine the real.” And these processes, to Buber, are at the heart of human development. Intersubjectivity is a developmental process in which increasing knowledge of others exists in tandem and in tension with knowledge of the self, interactively, recursively and, often, paradoxically. The higher levels of moral development (Kohlberg, 1976), ego development (Loevinger, 1976), and self development (Kegan, 1982) all involve greater tolerance for the individuality of the other and a complex experience of interpersonal life in which one’s separateness and connection are multilayered and shifting. Wisdom may develop out of relationships which challenge our views of ourselves and others, both cognitively and affectively (Kramer, 1990). The hallmark of increasing intersubjectivity is the capacity for recognition of another’s subjectivity (Benjamin, 1992), fully allowing others to be who they are as we are who we are. Simultaneously, we feel recognized by them. Separateness is transcended even as individual distinctiveness is confirmed (Erikson, 1966 as cited in Erikson, Erikson & Kivnick, 1986). Throughout life, other people may be experienced in four different ways: The other may be not be differentiated at all, as in merger; the other may be experienced as a need satisfier, an object who may or may not be internalized as part of the self; the other may be felt as a self-object (Kohut, 1977), separate but still part of the self; or the other may be represented as fully a subject, related to oneself but operating from a separate center. Recognition of the other as subject is an unevenly realized task of development. At times, we may recognize someone as a separate subject— only in the next moment to experience him as a self-object. Or we may acknowledge the subjectivity of some people but treat others as need gratifiers. As development progresses (optimally), there is an increase in intersubjective awareness, but this does not eliminate the other processes. With intersubjective functioning and the capacity to enjoy mutual recognition with another subject come the concomitant capacities for empathy, responsiveness, and concern. Intersubjectivity does not imply a state of interpersonal harmony—that would be a sterile form of conformism. Processes of projection, introjection, projective identification, and other forms of distortion occur throughout life, leaving us always with the task of sifting through and reworking our inner experience of others and self. Living is a process of breakdown and repair in relationships, discord followed by increases in understanding. To the extent that we can accomplish this, we grow wise and integrated. The confrontation with otherness takes place in small ways in an adult life, although these moments may feel quite dramatic to the individual. Rarely do we as psychologists have an opportunity to witness them in situ unless we are therapists 7 where we see in our patients the dawning and then flowering ability to more fully take in another person. A recent example from my teaching, however, comes to mind. In a graduate seminar on depth interviewing for research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Dafna, a 35-year-old woman doing doctoral research on attitudes toward the Holocaust, interviewed Abdul, an Israeli Arab man, also a student in the class. This young man was quite candid and forthright in his responses and related to her in detail his efforts to make sense of the Holocaust. But his views were so far from anything she expected or had ever heard before, so utterly shocking, that she came to me after the interview in tears, filled with outrage and despair that anyone— anyone—could assert that the Holocaust never happened and was merely a Zionist hoax. I tried to empathize with her distress and attempted to help her see that this presented an excellent opportunity for her to try to understand someone who looks at the world differently from the way she—and everyone she knows—looked at it. But she couldn’t move out of her fury and was now beginning to include me as someone who, in not joining her in her outrage, condoned such a despicable view. I asked her to transcribe the tape so that we could try to look at it together. Once she did this, Dafna realized that what her interviewee had to say was far more complex than a simple-minded assertion that the Holocaust didn’t happen. In fact, he never said this at all. Rather, he was trying to explain the particular meaning the Holocaust had for the Palestinian people and how he, as an Arab, had to integrate that with the dominant Jewish society in which he lived and studied. After much work and discussion, Dafna wrote her final summary of what she learned from the interview: This interview was quite a hard experience for me. However, during the interview and, upon reflection, I felt that it had been a learning experience. First, I have never been exposed to the opinions and views that the interviewee holds and presented. Second, I forced myself to listen and controlled my responses in order to “get the task done.” The fact that I managed to accomplish the task surprised me, and I was pleased that I had done so. I feel that the feelings I had while listening to the interviewee were very strong. I was hurt and offended by his opinions. I did not believe what he was actually saying; that is, not the content so much but that he was saying it. I also feel that what he said was very strong and on a certain level, it was essentially an anti-Semitic viewpoint. I do not believe that he would have thought so. I believe that some of the shock that I experienced was that these views did not seem to “suit him.” He appeared before and still appears to be an open, sensitive soul, and his words did jar me. I believe that the interviewee had a script, according to the demands of his beliefs and ideology.… I believe that he is firm in his convictions and completely loyal to his beliefs, yet he 8 was very stuck in his rhetoric and did not appear to even want to budge, to try and examine some of the things he said. When he experienced moments of reflection regarding what he said, he immediately gave another statement which suited his script. (I suppose that these moments, even if moments, are the windows.) The interviewee displayed two very strong, yet contradictory “feelings.” He was angry at the Israelis, the Zionists and the State of Israel, yet he felt a curiosity about Jews and the Holocaust. He claimed to be part of their world, a world which he was open to examine. Yet he was opposed to the institutions of the State and of Zionism: Yad Vashem, the army, etc…. I felt that at a certain point I began to correct him rather than try to understand how he got to the information he had.… I feel that the whole feeling of shock that I experienced inhibited me from telling about the other moments: moments of dialogue that he had with himself and some of the more gentle moments of the interview. I quote this write-up at length to demonstrate the multi-layeredness of this growth-producing moment as Dafna is poised between her “projecting” style—i.e., it is the interviewee who is stuck in a rigid script—and her genuine efforts to integrate his difference and his wholeness even in the face of her disgust with him. She hasn’t yet arrived; she teeters between wanting to reject and dismiss him and wanting to embrace and empathize with him. If (when) she succeeds with this, she will have moved ahead in wisdom and will see it, upon reflection, as an experience of personal integrity. These are the turning points of adult growth in wisdom and integrity and constitute the experience of greater knowledge about relationships. Later, Abdul was able to tell Dafna, in a kind way, that he was aware of her shock and she was able to acknowledge this to him. It seemed to be an important encounter for them both. They were able to acknowledge and continue to be who they were with a greater understanding and mutual empathy across difference. The capacity to embrace difference in relationship enlarges the self, expanding the repertoire of representations that one carries of people who inhabit the world we share, both sharpening the boundaries of the self and connecting the self in deeper ways to others. Wisdom in relationship involves accepting difference without assimilating the self to the other (through identification) or reducing difference to sameness (Benjamin, 1994; Sampson, 1993). Paul Wink and Ravenna Helson (1997) regard wisdom as insight and knowledge regarding oneself and the world. This involves dealing with matters that are uncertain, entailing sensitivity to context, relativism, and paradox. This is a soulful knowing in which one feels a deeper and more meaningful connection to others who are experienced in their contradictory and often frustrating wholeness. The women I have followed and learned from for 22 years have all had similar moments that led to increases in their understanding of others and therefore wisdom. 9 Amanda, for example, increased in her sense of wisdom after her husband was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm. The critical decision for me was to let my husband make the decision about what had to be done, even though I was a nurse and knew more about it. They had told him that without the surgery he would most likely die within six months but that with the surgery he faced a high chance of having major brain damage. I felt that was something I couldn’t decide for him. Had he chosen not to have the surgery, I would have supported him in that. I think he went into surgery thinking that he would be all right after surgery. He never really believed it would happen to him. I knew it probably would and what that meant. I felt it was such a big decision that I didn’t want to make it for him. I told him I would stand by whatever he decided. That was tough to do. If he did have major damage afterwards, I knew what that would mean in terms of recovery. But he showed determination that I’m not sure I would have had in that situation. He had a lot of fight in him from the beginning and has exceeded anyone’s expectations in terms of his recovery. With what he went through, I have a newfound respect for him and for his strength. Most men are babies about illness, but his stamina wouldn’t allow him to accept the limitations that others kept putting on him. I think he also saw a strength in me. I held things together. I worked. I took care of the kids, visited him every day. It brought us closer. We found each other. We care about each other. We’ve been through some rough times together and I can see where this could drive people apart. One thing we’re struggling with right now is that he wants to keep reliving what he’d been through and my daughter and I want to say, Aren’t you over it yet? But we’ve really come through it stronger. Still, it has been hard for Amanda to adjust to his cognitive impairments: I feel like I need to help him and be a teacher almost and there are times that I resent it—not resent it but I forget it and then realize, Oh my God he didn’t catch what I said. Or I do something quickly and think he should be right there with me but he’s not. And it’s frustrating. But then I think, What if it were me? How would I want someone to treat me? The kids, too, have been very good with him. People can say, its horrible and I hate it, but... We note here that Amanda is struggling to acknowledge and find a place for her resentment about her own loss. Logically, she knows it is irrational to resent her husband for what he is physically incapable of doing, and yet this is what she feels— 10 but quickly retracts. We note that she ends her statement by projecting her despairing feelings on nameless others, and we recognize that this is exactly what she is trying so hard to integrate. When she accomplishes this, she will be adding to the already considerable wisdom and integrity that she has already created. Erikson (1968) says that the mature ego, “through the constant interaction of maturational forces and environmental influences, [develops a] certain duality between higher levels of integration, which permits a greater tolerance of tension and of diversity, and lower levels of order where totalities and conformities must help to preserve a sense of security” (p81–2). The higher order, Erikson calls “wholeness”; the lower, “totality.” It is this movement toward wholeness that the individual experiences as wisdom, the affective sense of being able to tolerate the tension of difference. Wholeness and wisdom thus contradict the mechanistic model of humanity Erikson deplores in the quotation cited in the epigraph; neither can exist without friction, sputtering, or smoke. Integrity consists in the sense that contradictions coexist, that one’s mistakes in life were necessary, that one’s life course is multi-determined and contains irrational as well as rational elements—and that these insights are true for all the significant others in one’s life as well. And the project of knowing others is, as Elizabeth Spelman (1988) puts it, “strenuous.” As we approach the end of the twentieth century, wisdom about relationships is the greatest challenge as we increasingly recognize the diversity of the world in which we live. How do we know those who are other from us without stereotyping them or denying their difference? How can we build a world where we can honor our differences and live together? These are the questions most in need of everyone’s wisdom. The Enlargement of Care A second major path toward wisdom and integrity in adulthood is the enlargement of the meaning of care. Most of the women I have studied, as we saw above, locate their sense of pride and meaningfulness in their capacity to care for others. Without much reflection, they base their sense of integrity in their ability to provide valued emotional resources for others. Actively engaged in professional work, these women also define the meaning they find in their work in terms of feeling they have had some positive impact on the lives of others. They wonder about what their work really meant, whether it felt essential, whether it really mattered to someone that they were doing what they were doing in the way that they were doing it. It isn’t enough to be “good at” their job. They want their work to create impact, to mean something.4 In Erikson’s developmental model, care is the virtue of generativity, the project of adulthood where one seeks to provide for the growth of others, to “pass it on” in George Vaillant’s phrase. The activities of caring are those of generativity— taking care of children, mentoring others, serving the community, etc. Yet, a person’s reflection on the meaning of these activities, their understanding of their impact in the larger scheme of things belong, I believe, to the growing sense of integrity (versus despair). 11 Care is found at all developmental levels, but it evolves into an ethical system (Noddings, 1984) and a core of morality (Gilligan, 1982). Never, however, does care lose its base in affect: emotion and thought are integrated in care, which is experienced as deriving from the heart as well as the mind. Thus, the experience of being caring, in the mature adult, is accompanied by self-reflective appraisals of the self as having integrity and finding meaning. Care can be experienced as transcendent—it is a form of connection to others in the world where the self has reached past its own boundaries to etch what is outside. The experience and integration of care changes and develops across the life cycle—from the idealism of the late adolescent ready to dream impossible dreams and change the world to the realism of the mature adult who recognizes the impossibility of the dreams yet continues to offer the resources of the self in the interest of tending some aspects of the world. It is around the personal quest to be a “good enough” carer that many adult crises of integrity revolve.5 Care involves the effort to balance the interests of the self and the interests of a differentiated other. Care requires thinking and strategy as well as the affective intention to invest the self in another (Ruddick, 1989). We offer our help and sustenance in momentary as well as grand ways. We visit a sick or bereaved friend or bring a funny gift to someone we like. And we care by taking on the cares of those we love (Gilligan, 1990)—worrying with them, intervening for them. We tend relationships as well as individual others by enacting dozens of small practical rituals that strengthen our bonds: looking after the home, taking charge of the neighborhood get-together, etc. (Bateson, 1989). It is in these myriad acts, taken together, that midlife women are apt to locate their sense of integrity. They locate their value in the hearts of those whom they have touched. Beyond our generative wish to care, we learn much as adults about the limits of our caring. The perception of need may be faulty and the intention to care may be experienced by the other as suffocating, controlling, or patronizing (“But I meant well.”) What we offer as care may not be regarded as such by those toward whom we extend it. I want my 19-year-old daughter to call me every night while she is on a road trip because I worry about her and want to be sure she is safe. But she regards this request as intrusive and confining—she wants to be in charge of her own safety. My growth then involves finding other ways to express my love for her and to manage my worry. This isn’t easy but I grow wiser about what it means to be a mother and what it means to let go of a child. These lessons are by no means confined to life at home. The workplace daily provides challenges to care. Marlene, one of the women in my longitudinal study, made personal sacrifices to train as a nurse-midwife and work to promote women’s health in the inner city. Initially, she had high hopes for how much change she could effect, hopes that were quickly subjected to disappointments. At the time of the interview, she had integrated a clearer vision of what she could and could not accomplish, but this came after a long process of inner struggle. As our knowledge about care expands, we become more aware of its complexities. We become conscious of the ease with which we can mindlessly regard 12 ourselves as caring people, so we begin to search out the ways in which we have become hardened, oblivious to the plight of others, or incapacitated in terms of response. Racists regard themselves as moral, loving people. A mature effort at a sense of integrity is to learn to identify the racism in oneself—and in us all. I remain haunted by the Nazi doctors who tortured people in the name of science all day, then went home to be loving fathers and husbands to their families at night, regarding themselves, on balance, as ethical and caring human beings (Lifton, 1986). Mindfulness about care forms a formidable path of integrity for women in middle adulthood. Care can hurt as well as help. Caring for people in the larger society engages us in political realities that confound the simple impulse to help. And care for people in other societies, care for the world environment, eludes most of us even as we sigh in despair over the morning newspaper. The experience of integrity and the accretion of wisdom in middle adulthood is created when one’s intimate relationships and generative activities, the hallmarks of Erikson’s sixth and seventh stages of development, evoke a sense of meaning in a transcendent sense. Understanding more about others and finding ways to care for them in welcome and useful ways enlarge the self and lead to enlightenment which may transform a woman’s view of the world and her place in it. Through reflection on their experiences in relationships, women come to find new significance in old truths, knowing what they always in some sense knew, but knowing it in a new, deeper sense. Endnotes 1. These responses are very similar to what Erikson, Erikson, and Kivnick (1986) heard from the elders they interviewed about their experience of meaningfulness in their old-age life review. 2. Even Erikson gave voice to this position by asserting that “much of a young woman’s identity is already defined in her kind of attractiveness and in the selective nature of her search for the man (or men) by whom she wishes to be sought (1968, p.263).” This has been much quoted and much maligned. But Erikson later said that this is determined by “the role possibilities of her time.” 3. Gilligan (1990) 4. Helson and McCabe (1993) also found that women in search of new identity in midlife most wanted to achieve a status where they had something valuable to give to others. 5. Speaking from a feminist point of view, Luepnitz (1988) suggests that the discussion of nurturance has been a taboo topic under patriarchy which is contemptuous and frightened of mothering. References Apter, T., & Josselson, R. (1998). Best friends: The pleasures and perils of girls’ and women’s friendships. New York: Crown. Ballou, M. (1995). Women and spirit: Two nonfits in psychology. Women & Therapy, 16, 2/3, 9 –20. Bateson, C. (1989). Composing a life. New York: Penguin. New York: Crown. 13 Benjamin, J. (1992). Recognition and Destruction. In N. J. Skolnick & S. C. Warshaw (Eds.), Relational Perspectives in Psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press. Benjamin, J. (1994). The Shadow of the other (Subject): Intersubjectivity and feminist theory. Constellations 1:231–54. Birren, J. E., & Fisher, L. M. (1990). The elements of wisdom: overview and integration. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Bradley, C. L, & Marcia, J. E. (1998). Generatibity-stagnation: A five category model. J. Personality, 66, 1, 40–64. Bradley, C. L. (1997). Generativity-stagnation: Development of a status model. Developmental Review, 17, 262–290 Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Buber, M. (1965). The knowledge of man. New York: HarperCollins. Chandler, M. J., & Holliday, S. (1990). Wisdom in a postapocalyptic age. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Clinchy, B. M. (1996). Connected and separate knowing: Toward a marriage of two minds. In N. Goldberg, J. Tarule, B. Clinchy, & M. Belenky (Eds.) Knowledge, difference and power. New York: Basic Books. Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: Norton. Erikson, E. H., & J. M. Erikson (1997). The life cycle completed. New York: Norton. Erikson, E. H., Erikson, J. M., &. Kivnick, H.Q. (1986). Vital involvement in old age. New York: Norton. Gilligan, C. (1990). Joining the resistance: Psychology, politics, girls and women. Michigan Quarterly Review, 29, 501–536. Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. Heilbrun, C. G. (1988). Writing a woman’s life. New York: Ballantine. Helson, R., & McCabe, L. (1994). The social clock project in middle age. In B. Turner & L. Troll (Eds.), Women growing older: Psychological perspectives. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Jordan, J. (1986.) The Meaning of Mutuality. Work in progress. Wellesley, MA.: The Stone Center. Josselson, R. (1978). Finding herself: Pathways to identity development in women. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Josselson, R. (1992). The space between us: Exploring the dimensions of human relationship. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 14 Josselson, R. (1996). Revising herself: The story of women’s identity from college to midlife. New York: Oxford University Press. Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kohlberg, L. (1976). Collected papers on moral development and moral education. Cambridge, MA: Center for Moral Education. Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press. Kramer, D. A. (1990). Conceptualizing wisdom: the primacy of affect-cognition relations. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Labouvie-Vief, G. (1990). Wisdom as integrated thought: historical and developmental perspectives. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. England: Cambridge University Press. Lifton, R. J. (1986). The Nazi doctors: Medical killing and the psychology of genocide. New York: Basic Books. Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Luepnitz, D (1988). The Family Interpreted. NY: Basic Books. McAdams, D. P., & de St. Aubin, E. (1998). Generativity and adult development. Washington, DC: APA Books. Miller, J. B. (1976). Toward a new psychology of women. Boston: Beacon Press. Miller, M. (1999). Religious and ethical strivings in the later years: Three paths to spiritual maturity and integrity. In L.E. Thomas & S.A. Eisenhandler (Eds.), Religion, belief and spirituality in late life, New York: Springer. Mitchell, S. A. (1988). Relational concepts in psychoanalysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Noddings, N. (1984). Caring. Berkeley: University of California Press. Robinson, D. N. (1990). Wisdom through the ages. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Ruddick, S. (1989). Maternal thinking: Toward a politics of peace. Boston: Beacon. Sampson, E. (1993). Celebrating the other: A dialogic account of human nature. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Spelman, E. V. (1988). Inessential woman: Problems of exclusion in feminist thought. Boston: Beacon Press. Stolorow, R., & Atwood, G. E. (1992). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press. Swidler, A. (1980). Love and adulthood in American culture. In Themes of love and work in adulthood, by N. J. Smelser and E. H. Erikson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 15 Wink, P., & Helson, R. (1997). Practical and transcendent wisdom: Their nature and some longitudinal findings. Journal of Adult Development 4: 1–15. 16