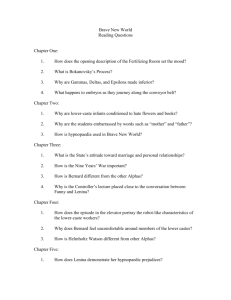

Brave New World

advertisement

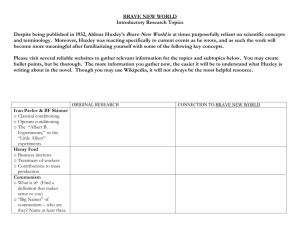

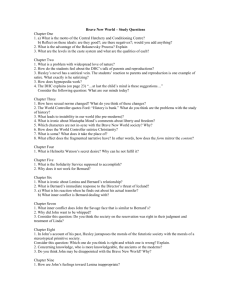

Brave New World is a novel written in 1931 by Aldous Huxley and published in 1932.Huxley then wrote Brave New World Revisited (1958), and Island (1962), his final novel. Title - Brave New World's title derives from Miranda's speech in William Shakespeare's The Tempest, Act V, Scene I: O wonder! How many godly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, That has such people in't. —William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act V, Scene I, ll. 203–206[5] This line itself is ironic: Miranda spent most of her life on an isolated island, and the only people she ever knew were her father and his servants, an enslaved savage, and spirits, notably Ariel. When she sees other people for the first time, she is overcome with excitement, and says the famous line above. Translations of the title often allude to similar expressions used in domestic works of literature in an attempt to capture the same irony: the French edition of the work is entitled Le Meilleur des mondes ("The Best of All Worlds"), an allusion to an expression used by the philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and satirised in Candide, Ou l'Optimisme by Voltaire (1759). Sources Literary - Huxley wrote Brave New World in 1931 while he was living in England. And said that Brave New World was inspired by the utopian novels of H. G. Wells, including A Modern Utopia (1905) and Men Like Gods (1923). Unlike the most popular optimist utopian novels of the time, Huxley gave a frightening vision of the future. George Orwell believed that Brave New World must have been partly derived from the novel We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, but Huxley denied. Historical - Although the novel is set in the future it deals with contemporary issues of the early 20th century: mass production, Russian revolution, the First World War (1914–1918) had transformed the world. The events of the depression in Britain in 1931, with its mass unemployment and the abandonment of the gold standard currency, persuaded Huxley to assert that stability was the "primal and ultimate need" if civilisation was to survive the present crisis. The characters sre mainly named after people known in England like Mustapha Mond, Resident World Controller of Western Europe, is named after Sir Alfred Mond whose vast technologically advanced plant near Billingham, north east England, Huxley visited shortly before writing the novel, which made a great impression on him. A trip in America and the reading of My Life and Work by Henry Ford produced in him a fear of Americanization in Europe. PLOT This book doesn’t really have a straightforward plot. It’s just a bunch of different ideas about what a perfect society would be like, according to the author. The beginning of the book describes the world they live in, Utopia. The director of "Hatcheries and Conditioning" talks about how their world works. They fertilize human female eggs, and babies grow in bottles. People control how babies are born and who the babies are. There are 5 classes of people. Alphas are the top class, Epsilons are the lowest. All the babies are kinda regulated by the government -- they control how the person will think and how smart the person is. They condition these babies to love life and like their job. The Controller talks about Utopia. He is one of 10 dudes who run the world. There are many principles in the society. One important thing is that the leaders don’t teach people about history because they don’t want people to be influenced by things in the past enough to try and change stuff in the present. Another big principle is that people have no emotions. They are given a drug called Soma which makes them permanently happy. Lastly, being in love is a crime, but having sex is okay. Then a story starts. Bernard Marx (main dude) is in the Alpha class. He loves this chick named Lenina Crowne. She works in the embryo room and is dating a scientist. She has a friend named Fanny who tells her to date other men. She likes Bernard, but doesn’t love him. Poor guy. She follows the law that you can’t love. Bernard is a bit weird in that he’s different than most of the people in the alpha class. He has a friend named Helmholtz Watson who is good at everything, but hates his job, which is writing propaganda. Then Bernard takes Lenina to some savage reservation in North America. The Director of Utopia tells them about his trip to the reservation. He tells them he brought some chick (Linda) who disappeared when they were there. Then the director gets pissed at Bernard because Bernard is a non-conformist (he doesn’t do what everyone else is doing). Bernard and Lenina go to the reservation. They meet this savage named John. Turns out John is the son of the director. Bernard figures out that the woman the director brought to the reservation got pregnant. Getting pregnant is against the law in Utopia so the director doesn’t talk about it. The woman got lost while on the reservation and had to stay there and give birth there. John has only heard about Utopia. He likes to read Shakespeare. Bernard brings John and his mom back to Utopia. The Director tries to get Bernard kicked out, but when he shows everyone the woman who the director got pregnant and his son, they laugh at the director. Everyone is curious about the savage (John). His mom (Linda) goes into a coma. John goes around and sees the sites but he doesn’t like Utopia. Then everyone thinks that Lenina is doing it with John the savage. She isn’t though. Even though he has fallen in love with her, he is a romantic so he doesn’t wanna have sex too soon. She wants him in a big way, and comes over to his place and strips. He kicks her out and calls her a whore. Then John finds out his mom is sick. He goes to the hospital and is sad. But the main dudes of Utopia don’t like his display of emotion because they teach everyone to be happy and that death is a happy thing. John, Bernard, and Bernard’s friend, Helmholtz are arrested. The Controller explains to them what Utopia is all about. Bernard is exiled to Iceland (between USA and England), Helmholtz is sent to the Falkland Islands (off South America), and John is kept in England. John is made to live a life of solitude. All the Utopians wanna kill John. Lenina joins them, and John kills himself. References "Our Ford" is used in place of "Our Lord", as a credit to popularising the use of the assembly line. Huxley's description of Ford as a central figure in the emergence of the Brave New World might also be a reference to the utopian industrial city of Fordlândia commissioned by Ford in 1927. "Our Freud" is sometimes said in place of "Our Ford" due to the link between Freud's psychoanalysis and the conditioning of humans, and Freud's popularisation of the idea that sexual activity is essential to human happiness and need not be limited to procreation. It is also strongly implied that citizens of the World State believe Freud and Ford to be the same person. H. G. Wells, "Dr. Wells", British writer and utopian socialist, whose book Men Like Gods was an incentive for Brave New World. "All's well that ends Wells" wrote Huxley in his letters, criticising Wells for anthropological assumptions Huxley found unrealistic. Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, whose conditioning techniques are used to train infants. William Shakespeare, whose banned works are quoted throughout the novel by John, "the Savage". The plays quoted include Macbeth, The Tempest, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, King Lear, Troilus and Cressida, Measure for Measure and Othello. Mustapha Mond also knows them because he, as a World Controller, has access to a selection of books from throughout history, including the Bible. Thomas Robert Malthus, whose name is used to describe the contraceptive techniques (Malthusian belt) practised by women of the World State. Reuben Rabinovitch, the character in whom the effects of sleep-learning, hypnopædia, are first noted. John Henry Newman, Mustapha Mond discussed Cardinal Newman with the Savage after reading a quote from his book NAMES The limited number of names that the World State assigned to its bottle-grown citizens can be traced to political and cultural figures who contributed to the bureaucratic, economic, and technological systems of Huxley's age, and presumably those systems in Brave New World:[17] Bernard Marx, from George Bernard Shaw (or possibly Bernard of Clairvaux or possibly Claude Bernard) and Karl Marx. Henry Foster, from Henry Ford American industrialist, see above. Lenina Crowne, from Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik leader during the Russian Revolution. Fanny Crowne, from Fanny Kaplan, famous for an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Lenin. Ironically, in the novel, Lenina and Fanny are friends. George Edzel, from Edsel Ford, son of Henry Ford. Polly Trotsky, from Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionary leader. Benito Hoover, from Benito Mussolini, dictator of Italy; and Herbert Hoover, then-President of the United States. Helmholtz Watson, from the German physician and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz and the American behaviorist John B. Watson. Darwin Bonaparte, from Napoleon I, the leader of the First French Empire, and Charles Darwin, author of The Origin of Species. Herbert Bakunin, from Herbert Spencer, the English philosopher and Classical liberal,[18] and Mikhail Bakunin, a Russian philosopher and anarchist. Mustapha Mond, from Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of Turkey after World War I, who pulled his country into modernisation and official secularism; and Sir Alfred Mond, an industrialist and founder of the Imperial Chemical Industries conglomerate. Primo Mellon, from Miguel Primo de Rivera, prime minister and dictator of Spain (1923–1930), and Andrew Mellon, an American banker and Secretary of the Treasury (1921–1932). Sarojini Engels, from Friedrich Engels, co-author of The Communist Manifesto along with Karl Marx: and Sarojini Naidu, an Indian politician. Morgana Rothschild, from J. P. Morgan, US banking tycoon, and the Rothschild family, famous for its European banking operations. Fifi Bradlaugh, from the British political activist and atheist Charles Bradlaugh. Joanna Diesel, from Rudolf Diesel, the German engineer who invented the diesel engine. Clara Deterding, from Henri Deterding, one of the founders of the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company, and Clara Ford, wife of Henry Ford. Tom Kawaguchi, from the Japanese Buddhist monk Ekai Kawaguchi, the first recorded Japanese traveller to Tibet and Nepal. Jean-Jacques Habibullah, from the French political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Habibullah Khan, who served as Emir of Afghanistan in the early 20th century. Miss Keate, the Eton headmistress, from nineteenth-century headmaster John Keate. Arch-Community Singster of Canterbury, a parody of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Anglican Church's decision in August 1930 to approve limited use of contraception. Popé, from Popé, the Native American rebel who was one of the instigators of the conflict now known as the Pueblo Revolt. John the Savage, after the term "noble savage" originally used in the verse drama The Conquest of Granada by John Dryden, and later erroneously associated with Rousseau. Furthermore, from the prophet John the Baptist. Comparisons with George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four Social critic Neil Postman contrasted the worlds of Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World in the foreword of his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death. He writes: What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions." In 1984, Postman added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we fear will ruin us. Huxley feared that our desire will ruin us. Journalist Christopher Hitchens, who himself published several articles on Huxley and a book on Orwell, noted the difference between the two texts in the introduction to his 1999 article "Why Americans Are Not Taught History": We dwell in a present-tense culture that somehow, significantly, decided to employ the telling expression "You're history" as a choice reprobation or insult, and thus elected to speak forgotten volumes about itself. By that standard, the forbidding dystopia of George Orwell's Nineteen EightyFour already belongs, both as a text and as a date, with Ur and Mycenae, while the hedonist nihilism of Huxley still beckons toward a painless, amusement-sodden, and stress-free consensus. Orwell's was a house of horrors. He seemed to strain credulity because he posited a regime that would go to any lengths to own and possess history, to rewrite and construct it, and to inculcate it by means of coercion. Whereas Huxley ... rightly foresaw that any such regime could break because it could not bend. In 1988, four years after 1984, the Soviet Union scrapped its official history curriculum and announced that a newly authorized version was somewhere in the works. This was the precise moment when the regime conceded its own extinction. For true blissed-out and vacant servitude, though, you need an otherwise sophisticated society where no serious history is taught. THEMES The Use of Technology to Control Society - Brave New World warns of the dangers of giving the state control over new and powerful technologies (ex. control of reproduction) It is important to recognize the distinction between science and technology: the State talks about progress and science, what it really means is the bettering of technology, not increased scientific exploration and experimentation. T The Consumer Society - Brave New World is a satire of the society in which Huxley existed, and which still exists today. The Incompatibility of Happiness and Truth - Brave New World is full of characters who do everything they can to avoid facing the truth about their own situations. The almost universal use of the drug soma is probably the most pervasive example of such willful self-delusion. Soma clouds the realities of the present and replaces them with happy hallucinations, and is thus a tool for promoting social stability. B The Dangers of an All-Powerful State - Like George Orwell’s 1984, this novel depicts a dystopia in which an all-powerful state controls the behaviours and actions of its people in order to preserve its own stability and power. But a major difference between the two is that, whereas in 1984 control is maintained by constant government surveillance, secret police, and torture, power in Brave New World is maintained through technological interventions that start before birth and last until death, and that actually change what people want. ty. Pneumatic - The word pneumatic is used with remarkable frequency to describe two things: Lenina’s body and chairs. Pneumatic is an adjective that usually means that something has air pockets or works by means of compressed air. In the case of the chairs (in the feely theater and in Mond’s office), it probably means that the chairs’ cushions are inflated with air. In Lenina’s case, the word is used by both Henry Foster and Benito Hoover to describe what she’s like to have sex with. Ford, “My Ford,” “Year of Our Ford,” etc. - hroughout Brave New World, the citizens of the World State substitute the name of Henry Ford, the early twentieth-century industrialist and founder of the Ford Motor Company, wherever people in our own world would say Lord” (i.e., Christ). This demonstrates that even at the level of casual conversation and habit, religion has been replaced by reverence for technology—specifically the efficient, mechanized factory production of goods that Henry Ford pioneered. Alienation - The motif of alienation provides a counterpoint to the motif of total conformity that pervades the World State. Bernard Marx, Helmholtz Watson, and John are alienated from the World State, each for his own reasons. Bernard is alienated because he is a misfit, too small and powerless for the position he has been conditioned to enjoy. Helmholtz is alienated for the opposite reason: he is too intelligent even to play the role of an Alpha Plus. John is alienated on multiple levels and at multiple sites: not only does the Indian community reject him, but he is both unwilling and unable to become part of the World State. The motif of alienation is one of the driving forces of the narrative: it provides the main characters with their primary motivations. Sex - Brave New World abounds with references to sex. At the heart of the World State’s control of its population is its rigid control over sexual mores and reproductive rights. Reproductive rights are controlled through an authoritarian system that sterilizes about two-thirds of women, requires the rest to use contraceptives, and surgically removes ovaries when it needs to produce new humans. The act of sex is controlled by a system of social rewards for promiscuity and lack of commitment. John, an outsider, is tortured by his desire for Lenina and her inability to return his love as such. The conflict between John’s desire for love and Lenina’s desire for sex illustrates the profound difference in values between the World State and the humanity represented by Shakespeare’s works. Shakespeare - Shakespeare provides the language through which John understands the world. Through John’s use of Shakespeare, the novel makes contact with the rich themes explored in plays like The Tempest. It also creates a stark contrast between the utilitarian simplicity and inane babble of the World State’s propaganda and the nuanced, elegant verse of a time “before Ford.” Shakespeare’s plays provide many examples of precisely the kind of human relations—passionate, intense, and often tragic—that the World State is committed to eliminating. Symbols Soma The drug soma is a symbol of the use of instant gratification to control the World State’s populace.