Originalism at Home and Abroad

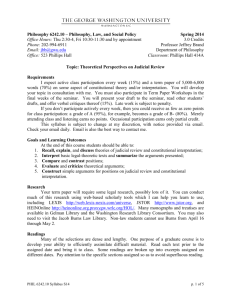

advertisement