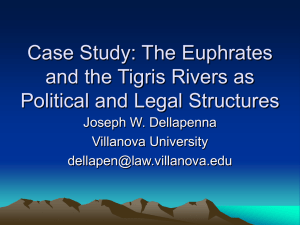

The Euphrates in Crisis

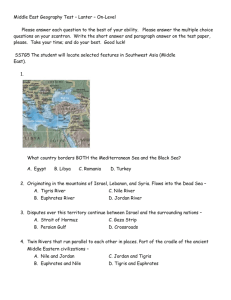

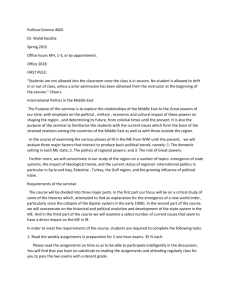

advertisement