Case Study 2 The Murray-Darling Basin

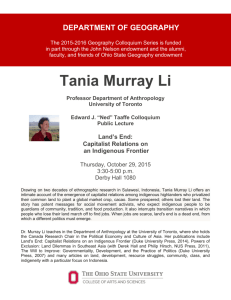

advertisement