LEADER EFFECTIVENESS AND INTEGRITY:

WISHFUL THINKING?

Robert Hooijberg

Nancy Lane

IMD 2005-1

IMD – International Institute for Management Development

Chemin de Bellerive 23

P.O. Box 915

1001 Lausanne

Switzerland

+41 21 618 0172

+41 21 618 0707 (fax)

Hooijberg@imd.ch

Copyright © 2005 Hooijberg and Lane

All Rights Reserved

ABSTRACT

Some researchers argue that leaders need integrity to be effective, while others argue that only

results matter, not how you get them. Few have empirically examined the impact of integrity on

leadership effectiveness. We examine the impact of leadership behaviors on effectiveness as well

as values such as integrity, flexibility and conformity, using a sample of top-level public service

managers. We find that the values of Integrity and Flexibility have a significant impact on

effectiveness over and above the impact of various leadership behaviors: Integrity for managers

and their peers and flexibility for direct reports and peers.

Key words: Leadership, integrity, effectiveness

2

LEADER EFFECTIVENESS AND INTEGRITY: WISHFUL THINKING?

Whenever you discuss leadership in executive seminars, a substantial proportion of the

participants will argue that leaders need integrity to function effectively. They find support for

their arguments in the works of authors such as Covey (1992) and Gardner (1993). Covey (1992:

61 and 108), for example, argues that followers of leaders without integrity sense the leaders’

“duplicity and become guarded” and describes integrity as “honestly matching words and

feelings with thoughts and actions, with no desire other than for the good of others.” Gardner

(1993: 33) argues that leaders need to demonstrate trust and reliability because people “cannot

rally around a leader if they do not know where he or she stands.” Other participants argue that

talk about integrity is nice but that most leaders follow a more Machiavellian view. By this they

mean that in the end only results matter. Machiavelli (1981: 101) himself put it quite eloquently

when he wrote that a prince “should appear a man of compassion, a man of good faith, a man of

integrity, a kind and a religious man. … In the actions of all men, and especially of princes,

where there is no court of appeal, one judges by the result. … The common people are always

impressed by appearances and results.”

While the debate continues in seminars around the world (and many news and talk

shows), few researchers have attempted to empirically explore the role that integrity plays in

leadership effectiveness. The current study takes a small step toward providing empirical

evidence by examining the impact integrity has on people’s perceptions of effectiveness in a

sample of public sector managers. Before we turn to the study and its results, we discuss some of

the conceptual work on integrity.

3

INTEGRITY

Becker (1998) reviews much of the work on integrity and finds that no standard

definition is used. One of the main problems he cites is that integrity is treated as synonymous

with honesty and fairness. For example, Yukl and Van Fleet (1990: 151) state that integrity

means that Kerr (1988: 126-127) does not define integrity, but rather lists ten components which

he calls the Ten Commandments of Executive Integrity: Tell the truth; obey the law; reduce

ambiguity; show concern for others; accept responsibility for the growth and nurturing of

subordinates; practice participation, not paternalism; provide freedom from corrupting

influences; always act; provide consistency across cases; and provide consistency between

values and actions.

Although no clear definition exists, integrity is supposed to be good for the organization.

People high in integrity make excellent candidates for leadership positions because they will not

steal organizational resources, treat others unfairly, or deceive themselves or others (Becker

1998: 160). This view is consistent with Badaracco and Ellsworth’s (1990) notion that valuedriven leaders make decisions in line with the purported values of the organization, and with

Srivastva et al.’s (1988) emphasis on congruence, consistency, morality, universality and

concern for others in their description of integrity. Covey (1992) emphasizes principle-centered

leadership, which he sees as the foundation of all leadership activities.

Becker further believes that most current tests of integrity do not measure integrity as he

defines it. Simons (1999:90), for example, defines the concept of Behavioral Integrity (BI) as

“the perceived degree of congruence between the values expressed by words and those expressed

through action. It is the perceived level of match or mismatch between the espoused and the

enacted. … BI, however, does not consider the morality of principles, but rather focuses on the

4

extent to which stated principles match actions.” Since integrity tests tend to invoke social

desirability responses (i.e., who would like to say they lack integrity?) and because of the

emphasis on action, Becker suggests we obtain assessments of integrity from others, such as

supervisors or peers (1998: 159).

The Role of Integrity in Organizations

Some researchers have examined the concept of integrity or concepts that are closely

related to integrity such as trust or ethics in organizational contexts. Schumm, Gade and Bell

(2003) studied the professional values of soldiers, which included loyalty to the US Army and

integrity among others. They used regression analysis to find that the best indicators of loyalty to

the Army were not integrity, as was expected, but rather military bearing and job commitment.

Kaptein (2003) developed a model called the Diamond of Managerial Integrity, which he argues

can be used to assess and improve the integrity of managers. Morrison (2001: 65) explores the

role of integrity in leading global companies and states that “Without integrity, managers will

never engender the goodwill and trust of the organization, both essential for effective

leadership.”

Davis et al. (2000) analyze the relationship between employees’ trust of a restaurant’s

general manager and its operational results. They analyzed means differences between

restaurants with high versus low levels of trust. They found that restaurants with high levels of

trust had significantly higher sales and higher profits, and had marginally but statistically

significant lower staff turnover. Treviño, Brown and Hartman (2003: 6) focused on the concept

of ethical leadership. They were interested in very senior executives, both board and non-board

members, because these leaders “create the ‘tone at the top’ that shapes the ethical climate and

ethical culture of the organization as well as the organization’s strategy” and therefore impact

5

the ethical culture of the entire organization. Their goal was “to inductively define the content

domain of ethical leadership based on a qualitative interview-based investigation.” (Treviño,

Brown and Hartman, 2003: 8). One of their conclusions is that “People perceive that the ethical

leader’s goal is not simply job performance, but performance that is consistent with a set of

ethical values and principles; and ethical leaders demonstrate caring for people (employees and

external stakeholders) in the process.” (Treviño, Brown and Hartman 2003: 21).

There have been few empirical studies on integrity, and of the ones that exist, only three

have examined the relationship between integrity, job satisfaction and leader effectiveness. Craig

and Gustafson (1998) developed a 31-item scale to measure employees’ perceptions of their

leaders’ integrity. The resulting instrument – the Perceived Leader Integrity Scale (PLIS) – was

then used to study the relationships between perceived integrity and job satisfaction. They found

significant positive correlation between the PLIS and job satisfaction. Parry and ProctorThomson (2002) used a revised version of the PLIS to analyze the relationship between Simons’

(1999) concept of behavioral integrity and leader effectiveness, as well as qualities that make up

transformational leaders and qualities that make up transactional leaders. Among other things,

they found that there is a significant positive correlation between the concepts of perceived

integrity and leader effectiveness. Morgan (1989) derived leadership assessment scales,

including one on integrity, and then analyzed their relationship to leader effectiveness. Using

regression analysis on the constructed scales, he found that integrity was the most important

variable related to trust, but motivation was the most important variable related to leadership

(Morgan, 1989). However, none of the studies mentioned examined what impact integrity has on

leader effectiveness.

6

INTEGRITY AND LEADERSHIP EFFECTIVENESS

The assumption in the literature on the need for integrity seems to be that it will have a

positive effect on leader and/or organizational effectiveness. We should, however, not take this

assumption for granted. Jackall (1988) shows convincingly that success can be obtained through

actions that seem to lack integrity, such as not taking responsibility for failure and taking credit

for successes one had barely anything to do with. Furthermore, it might be possible that top

managers in organizations care little about integrity as long as the work gets done. Research by

Hooijberg and Choi (2000), for example, shows that bosses of managers in both the public and

private sectors primarily associate goal achievement oriented behaviors with effectiveness, but

not mentoring, group facilitation, innovation, or monitoring behaviors. Direct reports, by

contrast, might be more concerned about integrity than the bosses because of their need for

consistency (e.g., Staw and Ross, 1980) and we believe that consistent behavior can be seen as

an indicator of integrity.

In fact, most leadership researchers have emphasized exclusively behavioral approaches

to leadership, rather than emphasizing integrity. A wide variety of theories emphasize behavioral

approaches to leadership, ranging from Fiedler’s LPC Theory (1967) to House’s Path-Goal

Theory to Quinn’s Competing Values Framework (1988) to Bass’ Transformational Leadership

Theory (1985) to Hooijberg and Quinn’s (1992) call for behavioral complexity. The notion of

behavioral complexity refers to the need for managers to perform a large repertoire of leadership

roles in the organizational arena in order to satisfy the demands of a wide variety of constituents.

Although this notion makes sense from a requisite variety perspective (Ashby, 1952), leaders run

the risk of being seen as spineless (Weick, 1978). They run that risk if people believe they vary

their behavior for political rather than for business reasons. This led Hooijberg, Hunt and Dodge

7

(1997) to call for more attention to be paid to values in leadership research, especially to the role

of integrity.

No empirical studies, however, have been conducted to analyze the relationship between

leadership behaviors, integrity, and effectiveness. In this paper we will test to what extent

performing multiple leadership roles (i.e., behavioral complexity) is associated with

effectiveness, as well as to what extent integrity is important for various stakeholders.

From previous research it is clear that various task-oriented and people-oriented

behaviors have significant positive associations with perceptions of leadership effectiveness.

Although research on 360-degree feedback shows that the strength of these associations depends

on who assesses the behavior and the effectiveness, overall a strong link between these behaviors

and effectiveness exists. Therefore:

Hypothesis 1:

All raters – self, direct reports, peers, and bosses – will strongly

associate performing multiple leadership roles with effectiveness.

As discussed before, a preponderance of the theoretical and managerial-practical research

seems to suggest a positive relationship between integrity and leadership effectiveness.

Therefore:

Hypothesis 2:

Integrity has a positive association with effectiveness for all raters.

Direct reports will be especially sensitive to consistency in the behavior of their

managers (Staw and Ross, 1980). In many theories (e.g. Kerr, 1988; Srivastva et. al., 1988)

consistency between words and actions is seen as a key component of integrity, therefore:

Hypothesis 3:

Direct reports will see an especially strong association between

integrity and leadership effectiveness.

Based on research by Hooijberg and Choi (2001) we know that bosses associate goaloriented behaviors far more strongly with effectiveness than any other behavior. In addition,

8

research by Hooijberg (1993) shows that bosses see managers who vary their behavior according

to who they are interacting with as more effective than those who do not vary their behavior.

Varying one’s behavior depending on the situation can easily be seen as lacking in integrity.

Jackall’s (1988) research, furthermore, seems to suggest that what matters is whether one can

associate oneself with success, not whether one was instrumental in actually creating success.

Given the emphasis on goal-oriented behaviors, an appreciation of variations in behavior,

and an emphasis on outcomes rather than means, we expect that:

H4:

Bosses associate goal-oriented behaviors in their managers, but not integrity, with

effectiveness.

METHODS

Sample

We collected information on the leadership styles, values and effectiveness of 175 bureau

chiefs and directors of a state government agency in the northeastern United States who

participated in a leadership-training program. The participants from the state government

department are the highest-level leaders who are not politically appointed. They work directly

under the commissioner and assistant commissioners appointed by the governor. The leaders in

this department must obey the laws, rules, and regulations that come down from their federal

counterpart and from the state legislature. They execute federal and state laws by reviewing and

granting permits and enforcing compliance with these laws. These bureau chiefs and directors

form an especially relevant sample for our study because they have to deal, almost daily, with

federal regulations, state regulations, members of the state legislature, the commissioner and

assistant commissioners, special interest groups, business representatives, and the general public.

One can see that they will need a large behavioral repertoire to deal with all of these

constituents. One can also see that, because these constituents pose widely different demands on

9

the bureau chiefs and directors, integrity may be hard to maintain and, at the same time, may be a

key ingredient for being effective.

The public sector organization strongly encouraged attendance at the leadership training

and participation of managers was close to 85%. Questionnaire data from the managers’ direct

reports, peers, and bosses were used to test the relationship between leadership behaviors,

integrity, and managerial effectiveness. On average four direct reports, two and a half peers, and

one and a half bosses provided feedback for each manager.

The 175 managers from the state government department represent 80% of all directors

and bureau chiefs (i.e., the top civil service level of management) in that department (overall size

is about 4,000 people). They are predominantly white (93%), male (70%), and on average 44

years old; they have been in their current position for an average of 5.9 years; and 45% of them

have a BA, 31% a Masters degree, and 4% a Ph.D.

Leadership Roles

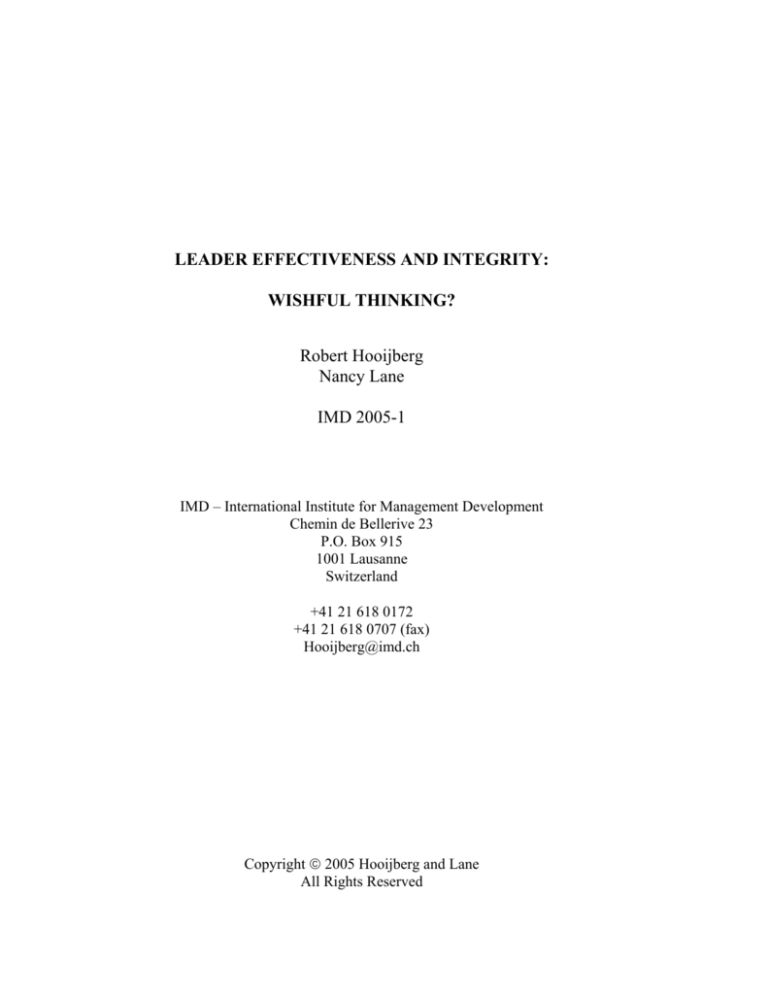

We used the leadership roles from Quinn’s (1988) Competing Values Framework (CVF)

to examine the impact of leadership behaviors on effectiveness. The CVF addresses internal and

external organizational demands on leadership; it also recognizes the paradoxical demands of

flexibility and control. These dimensions define four distinct leadership quadrants that address

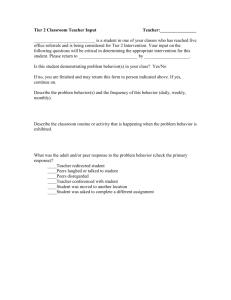

seemingly contradictory demands in the organizational arena (see Figure 1).

--------------------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here

--------------------------------------------The Task Leadership quadrant is characterized by a control orientation and a focus on the

environment outside the unit; it emphasizes setting and attaining goals. This quadrant contains

10

the Producer and Director roles. As a Producer, a manager is expected to motivate members to

increase production and accomplish stated goals. As a Director, a manager is expected to clarify

expectations, define problems, establish objectives, generate rules and policies, and give

instructions. The Stability Leadership quadrant is characterized by a control orientation and a

focus on the internal functioning of the unit; it emphasizes monitoring and coordinating the work

of the unit. This quadrant contains the Coordinator and Monitor roles. As a Coordinator, a

manager is expected to maintain the structure and flow of the system, coordinate staff efforts,

handle crises, and attend to technical and logistical issues. As a Monitor, a manager is expected

to know what is going on in the unit, to see if people are complying with rules and regulations,

and to check whether the unit is meeting its quotas.

The People Leadership quadrant is characterized by a flexible orientation and a focus on

the internal functioning of the unit; it emphasizes mentoring direct reports and facilitating group

process in the unit. This quadrant contains the Facilitator and Mentor roles. As a Facilitator, a

manager is expected to foster collective effort, build cohesion and teamwork, and manage

interpersonal conflict. As a Mentor, a manager is expected to develop people through a caring,

empathetic orientation. In this role the manager is helpful, considerate, sensitive, open,

approachable, and fair. The Adaptive Leadership quadrant is characterized by a flexible

orientation and a focus on the environment outside the unit; it emphasizes developing

innovations and obtaining resources for the unit. This quadrant contains the Innovator and

Broker roles. As an Innovator, a manager is expected to pay attention to changes in the

environment and to identify how to adapt to those changes and facilitate the process. As a

Broker, a manager is expected to meet with people from outside his/her unit to represent the unit

11

and to negotiate and acquire resources for the unit. These eight leadership roles will be used to

test our four hypotheses.

We used the 20-item survey Quinn (1988) developed to assess the frequency with which

managers perform the eight leadership roles of the CVF. The response scale ranged from “almost

never” (a score of 1) to “almost always” (a score of 7). We assessed the “frequency with which”

rather than “how well” managers perform the leadership roles in order to avoid creating

tautologies with the effectiveness items. Although Denison, Hooijberg, and Quinn (1995) found

strong support for the quadrant structure of the CVF, but not necessarily for the individual

leadership roles within the quadrants, we tried to replicate the original eight leadership roles.

Since we want to understand leadership effectiveness expectations from four

organizational role perspectives (managers, direct reports, peers and bosses), as suggested by

Keller (1986: 719), we aggregated the leadership role items by organizational role. We then

created four indices for each leadership role: one based on the responses of the managers

themselves; another based on the responses of the managers’ direct reports; a third based on the

responses of the managers’ peers; and finally one based on the responses of the managers’

bosses.

The Value of Integrity

Given that we did not find a clear, consistent, and validated framework of integrity in the

literature, we included in our questionnaire both values that have been associated with integrity

and values that may be seen as being in conflict with integrity. Craig and Gustafson (1998: 134)

indicate that their global indicators of integrity account for 81% of the variance in perceptions of

integrity. However, as we did not want to add 43 items to our questionnaire and since we wanted

12

to look at integrity in the context of other values, we assessed the contributions of values by

asking a series of questions about the participants’ values. The questions were posed as “To what

extent do you agree that the following principles and values guide the participant in his/her

work?” The response scales ranged from (1) very strongly disagree to (7) very strongly agree.

We therefore first examined the underlying factor structure of the values items. The values we

included in the questionnaire are a subset of the values items defined by McDonald and Gandz

(1992) and are as follows: Adaptability, flexibility, open-mindedness, cooperation, respect for

the individual, cautiousness, hierarchy, conformity, fairness, integrity, honesty, and merit.

Consistent with Becker’s (1998: 159) suggestion, we believe values are in the eye of the

beholder, and we therefore asked direct reports, peers, and bosses, in addition to the managers

themselves, to assess these different values. Just as we all have an implicit model of leadership,

so we have implicit models of what integrity means and we wanted to evaluate the respondents’

true understanding of these values.

Leadership Effectiveness

The effectiveness measures in this study do not attempt to assess the performance of the

work units or departments for which the middle managers in our study are responsible. Rather,

we used separate measures of perceived effectiveness for self, direct reports, peers, and bosses.

The effectiveness of the participating managers was assessed through five items that ask about

overall performance: (1) overall managerial success; (2) overall leadership effectiveness; (3) the

extent to which the manager meets managerial performance standards; (4) how well he/she

performs compared to his/her managerial peers; and (5) how well he/she performs as a role

13

model. These five items were measured on a five-point scale, with high scores indicating higher

levels of effectiveness.

As with the leadership roles, four indices of leadership effectiveness were constructed:

one based on responses of the managers; another based on the responses of the managers’ direct

reports; a third based on the responses of the managers’ peers; and finally one based on

responses of the managers’ bosses. The measures of effectiveness thus indicate how effective

managers are perceived to be by themselves, their direct reports, peers, and bosses.

Control Variables

Because we wanted to examine the relationships between leadership roles and

perceptions of leadership effectiveness, we needed to rule out alternative explanations of

perceptions of leadership effectiveness. Past studies have demonstrated that gender (e.g.,

Dobbins and Platz, 1986; Eagley and Johnson, 1990), age, managerial experience, and level of

education affect perceptions of leadership effectiveness (e.g., Bass, 1990). Therefore, we

included those four variables as control variables in this study.

RESULTS

For the values items we conducted Exploratory Factor Analyses using the Maximum

Likelihood method, as we did not find an existing, validated framework of values in the

literature. This exploratory work showed that for the four rating groups – the managers

themselves, their direct reports, peers, and bosses – the 12 values items could be represented by

three factors, which we labeled Integrity, Flexibility and Conformity. The factor structure that

emerged is shown in Table 1.

--------------------------------------------14

Insert Table 1 about here

--------------------------------------------While a three-factor structure was found for all four rating groups, there were small, but

significant differences. Table 1 shows that for all four rating groups, integrity is associated with

honesty. While that association is constant, the four rating groups differ in the other values they

associate with integrity. The managers themselves, in addition to honesty, also associate merit

and fairness with integrity. While the bosses and peers also associate merit with integrity, they

see fairness as more strongly associated with the Flexibility factor. The direct reports, by

contrast, see fairness as closely associated with integrity and honesty, but not merit. They see

merit as more closely associated with the Flexibility factor.

If we think of the exploratory factors as indicative of the respondents’ implicit values

frameworks, then we see that Integrity does not mean the same thing to all respondents and

neither does Flexibility. The Conformity factor, however, does hold the same meaning for all

four groups as the values conformity, hierarchy, and cautiousness emerge as a single factor each

time.

Rather than forcing a one-factor structure on all four groups, we decided to treat the

results as reflecting real differences in the value constructs of the respondent groups. These items

and factor clusterings were therefore taken forward into the Confirmatory Factor Analyses

(CFA).

15

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

We used LISREL 8.53 to conduct CFAs of the data because it takes measurement errors

into consideration, gives parameter estimates based on the maximum likelihood method, and

provides various indices of the extent to which the proposed covariance structural model fits the

data. In this study, we used five indices to assess the goodness of fit of the covariance structural

model: (1) chi-square value and its p-value; (2) chi-square divided by degrees of freedom; (3)

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA); (4) Incremental Fit Index (IFI); and (5)

Comparative Fit Index (CFI).

The most common goodness-of-fit index is the chi-square value. The rule of thumb is that

if the p-value of the chi-square statistic is greater than 0.05 (i.e., the chi-square value is nonsignificant), then the proposed model is acceptable (Hayduk, 1987). However, because the

traditional chi-square test is sensitive to sample size, a variety of indices that take sample size

into consideration have been developed. Marsh and Hocevar (1985) suggest using chi-square

divided by degrees of freedom, where values of less than 5.0 indicate good fit between model

and data. Browne and Cudek (1993) suggest using the RMSEA as the principal goodness-of-fit

index. They suggest that a value of RMSEA of less than 0.05 indicates a close fit and that values

up to 0.08 represent reasonable errors of approximation in the population. In addition, because

Bollen (1986, 1989a, 1989b) and Bentler (1990) have shown that IFI and CFI are much less

dependent on sample size, we also used IFI and CFI to assess the fit between the data and the

model. The values of IFI and CFI can vary between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a

good fit between data and model.

16

Confirmatory Factor Analysis on the Leadership Variables

We first performed four CFAs on the leadership roles, namely, one each for the managers

themselves, their direct reports, peers, and bosses. The eight-role leadership model, however, did

not generate a good fit with the data. The modification indices indicated that the fit between

model and data could be substantially improved by allowing the Producer, Director, and

Coordinator items to load on the same factor. These leadership roles lie close to each other in the

CVF and we labeled this factor the Goal Orientation factor in the subsequent LISREL analyses.

The results of this second CFA improved the overall fit and limited extremely high correlations

among the latent factors.

The goodness-of-fit indices for the CFAs for the four groups demonstrated good fit

between model and data and showed that the data confirmed the proposed six-factor structure.

Examination of the latent construct correlations supported the discriminant validity of the

constructs, because individual tests of the correlations indicated that they were significantly

lower than 1.0 (Bagozzi, 1980). The six-factor solution was also consistent with the factor

structure found by Hooijberg and Choi (2000, 2001). We then added the values and effectiveness

variables to the four CFAs with the six-factor structure described above to confirm the overall

factor structure of the independent and dependent variables in our study.

Tables 2 to 5 show the factor loadings for all leadership, values, and effectiveness factors

for the four groups, as well as the goodness-of-fit indices for the complete model.

--------------------------------------------Insert Tables 2-5 about here

---------------------------------------------

17

Correlations and Reliabilities

The tables with the correlations for the managers themselves, and their direct reports, peers, and

bosses are presented in Appendix A. Table 6 shows the Cronbach alpha coefficients for the

leadership roles, values, and effectiveness indices for all four of the samples. All Cronbach

alphas exceed the recommended 0.70 level (Nunnally, 1978).

--------------------------------------------Insert Table 6 about here

---------------------------------------------

Hierarchical Regression Analyses

To test the impact of integrity and the other values on effectiveness, we conducted a

three-step hierarchical regression analysis. In the first step, the control variables were entered; in

the second step, the six leadership roles of Innovator, Broker, Goal Orientation, Monitor,

Facilitator and Mentor were added; and finally, in the third step, the three values of Integrity,

Flexibility and Conformity were added. Table 7 shows the regression coefficients from the final

regression run as well as the R2 and delta-R2 for each step of the hierarchical regression analyses

for all four groups.

--------------------------------------------Insert Table 7 about here

--------------------------------------------None of the control variables have statistically significant associations with leader

effectiveness. Hypothesis 1, all groups – self, direct reports, peers, and bosses – will strongly

associate performing multiple leadership roles with effectiveness, is confirmed for all groups.

Three out six leadership roles have a significant association with self’s perceptions of

18

effectiveness. Two roles have significant associations with direct reports’, peers’, and bosses’

perceptions of effectiveness. Interestingly, no single leadership role is associated with

effectiveness in all four groups. The Innovator role is positively associated with effectiveness for

direct reports, and peers. The Broker role is only positively associated with effectiveness for

bosses. The Goal Orientation role is positively associated with effectiveness for self, direct

reports and bosses but not for peers. The Monitor role is positively associated with effectiveness

only for self. The Facilitator role is positively associated with effectiveness for self and peers.

Finally, the Mentor role is not associated with effectiveness for any of the raters.

Hypothesis 2, which states that Integrity has a positive association with effectiveness for

all raters, is partially confirmed. Integrity has a positive association with effectiveness for

managers and their peers; however, there is no positive association between Integrity and direct

reports’ or bosses’ perceptions of effectiveness. The changes in R2 are also significant for all

four groups when the three values factors are entered into the regression.

Hypothesis 3, which states that direct reports will see an especially strong association

between integrity and effectiveness, does not receive any support. In fact, contrary to our

expectations, we do not find a significant association between integrity and effectiveness, but

what we do find is a statistically significant association between flexibility and effectiveness.

Hypothesis 4, which states that bosses associate goal-oriented behaviors but not integrity

with leadership effectiveness, is confirmed. Indeed, bosses associate broker and goal-oriented

behaviors with effectiveness but none of the three values.

DISCUSSION

19

The results provide support for hypothesis 1; partial support for hypothesis 2; no support

for hypothesis 3; and full support for hypothesis 4. Hypothesis 1 stated that all groups would

associate performing multiple leadership roles with effectiveness. This hypothesis is confirmed

as the managers themselves associate three roles with effectiveness; and the direct reports, peers,

and bosses each associate two with effectiveness. The roles associated with effectiveness vary

depending on the respondents. Goal-orientation has both the strongest and most frequent (3 out

of 4) associations with effectiveness. The Mentor role is the only leadership role that does not

show a significant association with effectiveness, not even for the direct reports.

Hypothesis 2 stated that Integrity would have a positive association with effectiveness for

all raters. Based on the literature we certainly expected this hypothesis to be true. The results,

however, show a statistically significant association for the managers themselves and their peers,

but not for the direct reports and bosses. In light of hypothesis 3, we found especially surprising

the lack of a statistically significant association between Integrity and effectiveness for the direct

reports. Nevertheless, we did find a statistically significant positive association between

Flexibility and effectiveness in the results of the direct reports. Considering the elements of the

factor Flexibility outlined in Table 1, this indicates that direct reports see managers who value

flexibility, open-mindedness, cooperation, adaptability, respect for the individual and merit as

more effective than those who do not. The results indicate that Flexibility contributes more to

perceptions of effectiveness for direct reports than Integrity.

We found the lack of a statistically significant association between Integrity and

effectiveness for the bosses less surprising. As we stated in hypothesis 4, we expected the bosses

to focus primarily on goal-oriented behaviors and not integrity. The results support hypothesis 4

because the goal-orientation leadership role had the strongest association with effectiveness, but

20

there was no association with Integrity. The only other variable to have a statistically significant

association with effectiveness for bosses was the Broker role. It seems that the bosses in this

study are primarily concerned about getting the job done.

What Does It Mean?

Despite the increased attention given to integrity and its stated importance for leadership,

this study indicates that its relevance for leadership effectiveness is, at best, small. The largest

variation in perceptions of effectiveness is explained by leadership roles. The values, as a group,

add between 3% and 6% explained variance. In addition to the small percentage of explained

variance, Integrity does not have a statistically significant association with effectiveness for

direct reports and bosses.

We find the results related to integrity especially sobering. When authors like Covey

(1992) and Badaracco and Ellsworth (1990) write about the importance of integrity for

leadership, their arguments make sense. However, Jackall (1988) suggests that success is about

being associated with, rather than having caused, high performance.

The results of the factor analyses on the values items also indicate that integrity and

flexibility hold slightly different meanings for the different respondent groups. While integrity

and honesty are associated with each other for all four groups, merit and fairness are not.

Although Becker (1998) conceptually distinguishes integrity from honesty and fairness, our

research shows that managers and their direct reports, peers, and bosses do not.

Furthermore, the results from the direct reports also support some of Kerr’s (1988)

examples about the difference between the conceptual work on integrity and the realities

managers face in daily life. That is, if integrity means always stating what one really thinks (i.e.

21

honesty) or applying certain (un)written rules without exception, then one runs the risk of

hurting feelings and relationships and even getting the company in trouble. As Kerr (1988: 138)

states so eloquently, “the more confident were the prescriptions about how to behave with ethics

and integrity, the further removed was the author from the life of the everyday manager.” Adler

and Bird (1988: 248), for instance, cite as one example of executives lacking in integrity those

who “provide workers in one country with generous wages and pension programs while

providing neither in a neighboring country.” As they further point out, for an executive,

maximizing shareholder value is part of having integrity. They go on to state that as we expand

our thinking about integrity into the international realm, the issues become even more

complicated. Honesty may be appreciated in the U.S., but in Japan more emphasis is placed on

saving face.

How, then, can we follow Levinson’s (1988: 268) dictum: “To thine own self be true?”

His answer seems to come close to what our results show empirically when he says that

“executive integrity is promoted when members feel acknowledged for their responsiveness to

one another, their receptivity and creative efforts to understand others’ perspectives as well as

articulating their own” (Levinson, 1988: 318).

Integrity for Managers and their Peers

Integrity does not affect perceptions of effectiveness of direct reports and bosses; but it

does affect those of the managers themselves and their peers. While managers also see strong

associations between being goal-oriented, monitoring and facilitation, integrity has an effect over

and above those leadership behaviors. For peers, integrity has a positive effect over and above

generating new ideas and facilitation.

22

As the direct reports and bosses see no association between integrity and effectiveness,

do these results mean that managers are unnecessarily concerned with integrity? We would still

like to answer that question with a “no.” In terms of being seen as effective by direct reports and

bosses, executing one’s leadership roles is clearly most important. However, the reason one acts

with integrity is not only to be seen as effective by other parties: Acting with integrity is a way

for managers to stay true to themselves, as described by Levinson (1988: 268). While some

managers may do anything to reap ever greater financial rewards and/or power we would still

like to believe that the majority of managers want to be able to look at themselves in the mirror

and know they see someone who has integrity, and is fair and honest.

In terms of being seen as effective by one’s direct reports and bosses, these results

indicate that managers had better focus on delivering stated goals, influencing ideas, and

generating new ideas.

Implications for Practice

Our results do not support the notion, expressed by many authors, that integrity is

essential for leadership. Perhaps the question of why integrity should matter for effectiveness has

not received sufficient attention. If integrity is to a greater or lesser extent (depending on who

you ask) about honesty, fairness, and merit then why would being honest, fair, and focused on

merit result in your being perceived as more effective than someone who does not have these

qualities?

Telling your boss honestly that her plan for the introduction of a new product X in market

Y is a terrible idea, especially when you know how proud she is of this plan, may be good for

your sense of integrity, but perhaps not for improving her view of your effectiveness.

23

Emphasizing merit over length of service to the firm may sit well with the up-and-coming young

men and women, but not so well with the men and women who have invested 15 years or more

of their lives in the company.

In other words, while you may have – and may indeed act according to – clear guiding

principles, this does not automatically mean that those with whom you interact will appreciate it

when you exercise said guiding principles. We find the results of the direct reports especially

interesting in this regard. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find a statistically significant

association between integrity and effectiveness, but we did find a statistically significant positive

association between flexibility and effectiveness. Thus, being flexible, adaptable, cooperative,

open-minded, respectful of the individual, and valuing merit reflect not only positive values to

the direct reports but also values that make managers more effective. As such, these values have

a stronger association with effectiveness in the eyes of direct reports than integrity, honesty, and

fairness do.

The peer results for the values factors also have an interesting message for managers.

Peers want their colleagues to show both integrity and flexibility. Paradoxically, these results

represent both the toughest challenge and a solution for practicing managers. To us these results

say, “Yes, show us that you have integrity, that you are honest and that you value merit but do

not become rigid in the application of these values.”

Thus the authors believe that if you can balance integrity and flexibility, you can achieve

great results. Your integrity will keep you at peace with yourself and give your peers trust in

you. Your flexibility will make your direct reports and peers see that you are open to new ideas

and are willing to change your behavior when necessary. Expressing these values in your

24

interactions with your direct reports and peers will lead them to work harder and smarter for and

with you. This then should result in your being someone who delivers results.

As we stated before, the leadership role that bosses most strongly associate with

effectiveness is Goal-Orientation. This means that they want to see their managers meet their

stated goals, making sure that the unit’s goals are clearly identified and coordinated. Bosses also

care that their managers are able to influence events outside their unit, as they also associate the

Broker role with effectiveness. The implications for dealing with your boss are both sobering

and clear – get results and present great ideas.

Limitations of the Study

We see three important limitations in this study. First, we left the interpretation of

integrity up to the respondents. We neither tried to provide them with a shared definition of

integrity nor did we attempt to determine the extent to which people see the concepts of integrity

and honesty and fairness as distinct. The results indicate that differences exist in the

conceptualization of integrity and flexibility. Future research could perhaps conduct a more

anthropological study of how these concepts are distinct in people’s minds, and, what that means

for theory building. Not in the sense of providing a large pool of items à la Craig and Gustafson

(1998), but more in line with Kerr’s (1988) truly exploring what integrity means for real

executives.

Second, and in line with the previous point, we did not gather information to gain a more

in-depth understanding of the principles that guide these bureau chiefs and directors. It would be

helpful if future research on the role of integrity in leadership collected not only quantitative

25

assessments but also qualitative assessments. This would be research more along the lines of

what Jackall (1988) did.

Third, we used same-source data to examine the associations between values, leadership

roles, and effectiveness. We did this on purpose to better understand the implicit leadership

values frameworks people use to view the world of management. As the added variance

explained already is small, multi-method approaches would probably not dramatically alter the

overall results.

As Fritzche and Becker (1984: 166) said, “Little effort has been made to try to link

ethical theory to management behavior.” We hope that our study pushes further toward an

understanding of the role of integrity – and other values – in real-life organizations.

26

REFERENCES

Ashby, W. R.

1952 Design for a brain. New York: Wiley.

Adler, N.J., and F.B. Bird

1988 “International dimensions of executive integrity: Who is responsible for the world?” In S.

Srivastva et al. (eds.), Executive Integrity: The Search for High Human Values in Organizational

Life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Badaracco, J. L., and R. R Ellsworth

1990 “Quest for integrity.” Executive Excellence, 7: 3-4.

Bagozzi, R. P.

1980 Causal Models in Marketing. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bass, B. M.

1985 Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations. New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B. M.

1990 Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: A Survey of Theory in Research. New York, NY: Free

Press.

Becker, T.

1998 “Integrity in organizations: Beyond honesty and conscientiousness.” Academy of

Management Review, 23: 154-161.

Bentler, P.M.

1990 “Comparative fit indexes in structural models.” Psychological Bulletin, 107: 238-246.

Bollen, K. A.

1986 “Sample size and Bentler and Bonnet’s nonnormed fit index.” Psychometrika, 51: 375-377.

Bollen, K. A.

1989a Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York, NY: Wiley. 1989b “A new

incremental fit index for general structural equation models.” Sociological Methods and

Research, 17: 303-316.

Browne, M. W., and R. Cudeck

1993 “Alternative ways of assessing model fit.” In K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (eds.), Testing

Structural Equation Models. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Covey, S. R.

1992 Principle-Centered Leadership. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Craig, S. B., and S. B. Gustafson

27

1998 “Assessing employee perceptions of leader integrity.” Leadership Quarterly, 9: 127-146.

Davis, J.H., F.D. Schoorman, R.C. Mayer, and H.T. Tan

2000 “The trusted general manager and business unit performance: Empirical evidence of a

competitive advantage.” Strategic Management Journal, 21: 563-576.

Denison, D. R., R. Hooijberg, and R. E. Quinn

1995 “Paradox and performance: Toward a theory of behavioral complexity in managerial

leadership.” Organization Science, 6: 524-540.

Dobbins, G. H., and S. J. Platz

1986 “Sex differences in leadership: How real are they?” Academy of Management Review,

11: 118-127.

Eagley, A. H., and B. T. Johnson

1990 “Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin, 108: 233-256.

Fiedler, F. E.

1967 A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Fritzche, D. J., and H. Becker

1984 “Linking management behavior to ethical philosophy: An empirical investigation.”

Academy of Management Journal, 27: 166-175.

Gardner, J. W.

1993 On Leadership. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Hayduk, L. A.

1987 Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University

Press.

Hooijberg, R.

1996 “A multidirectional approach toward leadership: An extension of the concept of behavioral

complexity.” Human Relations, 49: 917-946.

Hooijberg, R., and J. Choi

2000 “Which leadership roles matter to whom?: An examination of rater effects on perceptions

of effectiveness.” Leadership Quarterly, 11 (3): 341-364.

Hooijberg, R., and J. Choi

2001 “The impact of organizational characteristics on leadership effectiveness models: An

examination of leadership in a private and a public sector organization.” Administration &

Society, 33 (4): 403-431.

Hooijberg, R., J. G. Hunt, and G.E. Dodge

28

1997 “Leadership complexity and development of the leaderplex model.” Journal of

Management, 23: 375-408.

Hooijberg, R., and R. E. Quinn

1992 “Behavioral complexity and the development of effective managerial leaders.” In R. L.

Phillips and J. G. Hunt, (eds.), Strategic Management: A Multiorganizational-Level Perspective.

New York, NY: Quorum.

House, R. J.

1971 “A path-goal theory of leader effectiveness.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 16: 321-338.

Jackall, Robert

1988 Moral Mazes. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Kaptein, M.

2003 “The diamond of managerial integrity.” European Management Journal, 21: 98-108.

Keller, R. T.

1986 “Predictors of the performance of project groups in R&D organizations.” Academy of

Management Journal, 29: 715-726.

Kerr, S.

1988 “Integrity in effective leadership.” In S. Srivastva et al. (eds.), Executive Integrity: The

search for high human values in organizational life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Levinson, H.

1988 “To thine own self be true: Coping with the dilemmas of integrity.” In S. Srivastva et al.

(eds.), Executive Integrity: The Search for High Human Values in Organizational Life. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Machiavelli, N.

1981 The Prince. Translated by George Bull. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Marsh, H. W., and D. Hocevar

1985 “Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher

order factor models and their invariance across groups.” Psychological Bulletin, 97: 562-582.

McDonald, P., and J. Gandz

1992 “Getting value from shared values.” Organizational Dynamics, 20: 64-77.

Morgan, R. B.

1989 “Reliability and validity of a factor analytically derived measure of leadership behavior and

characteristics.” Educational Psychological Measurement, 49: 911-919.

Morrison, A.

2001 “Integrity and global leadership.” Journal of Business Ethics, 31: 65-76.

29

Nunnally, J.

1978 Psychometric Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Parry, K. W., and S. B. Proctor-Thomson

2002 “Perceived integrity of transformational leaders in organisational settings.” Journal of

Business Ethics, 35: 75-96.

Quinn, R. E.

1988 Beyond Rational Management: Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High

Performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schumm, W., P. Gade, and D.B. Bell

2003 “Dimensionality of military professional values items: An exploratory factor analysis of data

from the spring 1996 sample survey of military personnel.” Psychological Reports, 23: 831-841.

Simons, Tony L.

1999 “Behavioral integrity as a critical ingredient for transformational leadership.” Journal of

Organizational Change Management, 12: 89-104.

Srivastva, S. and Associates

1988 Executive Integrity: The Search for High Human Values in Organizational Life. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Staw, B. M., and J. Ross

1980 “Commitment in an experimenting society: A study of the attribution of leadership from

administrative scenarios.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 65: 249-260.

Treviño, L. K., M. Brown, and L. P. Hartman

2003 “A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from

inside and outside the executive suite.” Human Relations, 56: 5-37.

Weick, K.

1978 “Spines of Leaders.” In M. W. McCall and M. M. Lombard (eds.), Leadership: Where Else

Can We Go?: 37-61. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Yukl, G., and D. D. Van Fleet

1990 “Theory and research on leadership in organizations.” In M. D. Dunette and L. M. Hough

(eds.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting

Psychologists Press.

30

TABLE 1

Values Factor Structure

Integrity

Integrity

Honesty

Merit

Fairness

Integrity

Integrity

Honesty

Fairness

Integrity

Integrity

Honesty

Merit

Self

Flexibility

Adaptability

Open-mindedness

Flexibility

Respect for the individual

Cooperation

Direct Reports

Flexibility

Adaptability

Open-mindedness

Flexibility

Respect for the individual

Cooperation

Merit

Peers and Bosses

Flexibility

Adaptability

Open-mindedness

Flexibility

Respect for the individual

Cooperation

Fairness

31

Conformity

Conformity

Hierarchy

Cautiousness

Conformity

Conformity

Hierarchy

Cautiousness

Conformity

Conformity

Hierarchy

Cautiousness

TABLE 2

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses for Self and Fit Indices

Self

Values

Leadership Roles Leadership

Leadership Roles,

Roles & Values Values &

Effectiveness

Innovator

X1: Experiments with new concepts and procedures

0.742

0.741

0.741

X2: Does problem solving in creative, clever ways

0.884

0.895

0.895

X3: Comes up with inventive ideas

0.934

0.924

0.924

X4: Influences decisions made at higher levels

0.702

0.669

0.702

X5: Gets access to people at higher levels

0.613

0.611

0.613

X6: Exerts upward influence in the organization

0.998

0.998

0.998

Broker

Goal Orientation

X7: Gets the unit to meet expected goals

0.664

0.672

0.655

X8: Sees that the unit delivers on stated goals

0.708

0.708

0.690

0.837

X9: Clarifies the unit’s priorities and direction

0.828

0.825

X10: Makes the unit’s role very clear

0.803

0.799

0.803

X11: Anticipates workflow problems, avoids crisis

0.742

0.738

0.753

X12: Keeps track of what goes on inside the unit

0.668

0.674

0.666

Monitor

X13: Maintains tight logistical control

0.629

0.683

0.693

X14: Compares records, reports, and so on to detect discrepancies

0.757

0.727

0.725

X15: Monitors compliance with the rules

0.816

0.786

0.775

X16: Facilitates consensus building in the work unit

0.660

0.671

0.698

X17: Surfaces key differences among group members, then works

participatively to resolve them

0.796

0.781

0.762

X18: Develops consensual resolution to openly expressed differences

0.708

0.717

0.714

Facilitator

Mentor

X19: Shows empathy and concern in dealing with subordinates

0.915

0.914

0.912

X20: Treats each individual in a sensitive, caring way

0.879

0.880

0.882

Integrity

X21: Fairness

0.695

0.693

0.694

X22: Integrity

0.866

0.870

0.871

X23: Honesty

0.864

0.853

0.850

X24: Merit

0.644

0.658

0.660

0.731

0.699

0.699

Flexibility

X25: Flexibility

X26: Open-mindedness

0.809

0.748

0.749

X27: Cooperation

0.716

0.745

0.743

X28: Adaptability

0.693

0.663

0.666

X29: Respect for the individual

0.745

0.802

0.803

Conformity

X30: Cautiousness

0.551

0.624

0.636

X31: Hierarchy

0.853

0.796

0.791

X32: Conformity

0.776

0.783

0.775

Table 2 (continued)

Effectiveness

Y1: Meeting of managerial performance standards

0.883

Y2: Overall managerial success

0.770

Y3: Comparisons to the person's managerial peers

0.620

Y4: Performance as a role model

0.867

Y5: Overall effectiveness as a manager

0.883

Goodness-of-fit indices for Complete Model

Chi-square

1484.480

Degrees of freedom

584

Chi-square/degrees of freedom

2.542

RMSEA

0.103

90% Confidence Interval for RMSEA

(0.0963 , 0.109)

CFI

0.862

IFI

0.863

33

TABLE 3

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses for Direct Reports and Fit Indices

Direct Reports

Values

Leadership

Roles

Leadership

Roles &

Values

Leadership

Roles,

Values &

Effectiveness

Innovator

X1: Experiments with new concepts and procedures

0.825

0.822

0.820

X2: Does problem solving in creative, clever ways

0.927

0.929

0.931

X3: Comes up with inventive ideas

0.932

0.931

0.930

Broker

X4: Influences decisions made at higher levels

0.807

0.808

0.806

X5: Gets access to people at higher levels

0.806

0.804

0.799

X6: Exerts upward influence in the organization

0.998

0.934

0.934

Goal Orientation

X7: Gets the unit to meet expected goals

0.707

0.713

0.717

X8: Sees that the unit delivers on stated goals

0.771

0.775

0.774

0.930

X9: Clarifies the unit’s priorities and direction

0.938

0.933

X10: Makes the unit’s role very clear

0.916

0.913

0.912

X11: Anticipates workflow problems, avoids crisis

0.764

0.771

0.774

X12: Keeps track of what goes on inside the unit

0.740

0.745

0.747

Monitor

X13: Maintains tight logistical control

0.855

0.855

0.855

X14: Compares records, reports, and so on to detect discrepancies

0.702

0.699

0.699

X15: Monitors compliance with the rules

0.846

0.849

0.848

Facilitator

X16: Facilitates consensus building in the work unit

0.869

0.867

0.866

X17: Surfaces key differences among group members, then works participatively to resolve

them

0.863

0.865

0.864

X18: Develops consensual resolution to openly expressed differences

0.820

0.821

0.822

Mentor

X19: Shows empathy and concern in dealing with subordinates

0.920

0.929

0.930

X20: Treats each individual in a sensitive, caring way

0.979

0.969

0.968

Integrity

X21: Fairness

0.810

0.812

0.813

X22: Integrity

0.911

0.911

0.914

X23: Honesty

0.912

0.910

0.907

X24: Flexibility

0.810

0.800

0.802

X25: Open-mindedness

0.852

0.860

0.861

Flexibility

X26: Cooperation

0.850

0.846

0.847

X27: Adaptability

0.799

0.805

0.806

X28: Respect for the individual

0.886

0.888

0.886

X29: Merit

0.805

0.800

0.800

Conformity

X30: Cautiousness

0.611

0.565

0.571

X31: Hierarchy

0.680

0.631

0.637

X32: Conformity

0.923

0.998

0.992

Table 3 (continued)

Effectiveness

Y1: Meeting of managerial performance standards

0.914

Y2: Overall managerial success

0.844

Y3: Comparisons to the person's managerial peers

0.858

Y4: Performance as a role model

0.940

Y5: Overall effectiveness as a manager

0.936

Goodness-of-fit indices for Complete Model

Chi-square

1343.09

Degrees of freedom

584

Chi-square/degrees of freedom

2.30

RMSEA

0.086

(0.0804 , 0.0925)

90% Confidence Interval for RMSEA

CFI

0.972

IFI

0.972

35

TABLE 4

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses for Peers and Fit Indices

Peers

Values

Leadership

Roles

Leadership

Roles &

Values

Leadership

Roles,

Values &

Effectiveness

Innovator

X1: Experiments with new concepts and procedures

0.800

0.802

0.801

X2: Does problem solving in creative, clever ways

0.909

0.912

0.909

X3: Comes up with inventive ideas

0.920

0.916

0.921

Broker

X4: Influences decisions made at higher levels

0.664

0.664

0.663

X5: Gets access to people at higher levels

0.821

0.822

0.818

X6: Exerts upward influence in the organization

0.998

0.879

0.879

Goal Orientation

X7: Gets the unit to meet expected goals

0.756

0.755

0.757

X8: Sees that the unit delivers on stated goals

0.892

0.891

0.891

0.795

X9: Clarifies the unit’s priorities and direction

0.798

0.794

X10: Makes the unit’s role very clear

0.801

0.802

0.802

X11: Anticipates workflow problems, avoids crisis

0.719

0.720

0.719

X12: Keeps track of what goes on inside the unit

0.750

0.754

0.752

Monitor

X13: Maintains tight logistical control

0.721

0.728

0.730

X14: Compares records, reports, and so on to detect discrepancies

0.774

0.765

0.765

X15: Monitors compliance with the rules

0.819

0.820

0.818

Facilitator

X16: Facilitates consensus building in the work unit

0.777

0.775

0.778

X17: Surfaces key differences among group members, then works participatively to resolve

them

0.818

0.823

0.825

X18: Develops consensual resolution to openly expressed differences

0.840

0.837

0.832

Mentor

X19: Shows empathy and concern in dealing with subordinates

0.964

0.962

0.962

X20: Treats each individual in a sensitive, caring way

0.928

0.930

0.929

Integrity

X21: Integrity

0.795

0.785

0.787

X22: Honesty

0.998

0.998

0.998

X23: Merit

0.479

0.463

0.465

Flexibility

X24: Fairness

0.719

0.731

0.734

X25: Flexibility

0.790

0.783

0.779

X26: Open-mindedness

0.857

0.858

0.856

X27: Cooperation

0.696

0.711

0.714

X28: Adaptability

0.702

0.865

0.682

X29: Respect for the individual

0.808

0.815

0.818

Conformity

X30: Cautiousness

0.769

0.791

0.792

X31: Hierarchy

0.721

0.706

0.706

X32: Conformity

0.875

0.862

0.861

Table 4 (continued)

Effectiveness

Y1: Meeting of managerial performance standards

0.888

Y2: Overall managerial success

0.847

Y3: Comparisons to the person's managerial peers

0.816

Y4: Performance as a role model

0.884

Y5: Overall effectiveness as a manager

0.912

Goodness-of-fit indices for Complete Model

Chi-square

1201.52

Degrees of freedom

584

Chi-square/degrees of freedom

2.06

RMSEA

0.081

90% Confidence Interval for RMSEA

(0.0745 , 0.0875)

CFI

0.959

IFI

0.959

37

TABLE 5

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses for Bosses and Fit Indices

Bosses

Values

Leadership

Roles

Leadership

Roles &

Values

Leadership

Roles,

Values &

Effectiveness

Innovator

X1: Experiments with new concepts and procedures

0.894

0.893

0.848

X2: Does problem solving in creative, clever ways

0.830

0.830

0.798

X3: Comes up with inventive ideas

0.895

0.896

0.850

Broker

X4: Influences decisions made at higher levels

0.863

0.856

0.822

X5: Gets access to people at higher levels

0.728

0.722

0.685

X6: Exerts upward influence in the organization

0.998

0.900

0.900

Goal Orientation

X7: Gets the unit to meet expected goals

0.761

0.766

0.726

X8: Sees that the unit delivers on stated goals

0.849

0.852

0.815

0.740

X9: Clarifies the unit’s priorities and direction

0.775

0.772

X10: Makes the unit’s role very clear

0.863

0.861

0.821

X11: Anticipates workflow problems, avoids crisis

0.790

0.788

0.754

X12: Keeps track of what goes on inside the unit

0.811

0.811

0.769

Monitor

X13: Maintains tight logistical control

0.752

0.752

0.716

X14: Compares records, reports, and so on to detect discrepancies

0.863

0.855

0.814

X15: Monitors compliance with the rules

0.707

0.715

0.679

Facilitator

X16: Facilitates consensus building in the work unit

0.809

0.826

0.781

X17: Surfaces key differences among group members, then works participatively to resolve

them

0.813

0.806

0.783

X18: Develops consensual resolution to openly expressed differences

0.860

0.855

0.805

Mentor

X19: Shows empathy and concern in dealing with subordinates

0.901

0.961

0.921

X20: Treats each individual in a sensitive, caring way

0.975

0.914

0.867

0.941

Integrity

X21: Integrity

0.998

0.998

X22: Honesty

0.930

0.926

0.884

X23: Merit

0.725

0.719

0.716

Flexibility

X24: Fairness

0.730

0.717

0.685

X25: Flexibility

0.831

0.818

0.773

X26: Open-mindedness

0.872

0.845

0.799

X27: Cooperation

0.830

0.842

0.800

X28: Adaptability

0.785

0.788

0.755

X29: Respect for the individual

0.846

0.870

0.838

Conformity

X30: Cautiousness

0.566

0.573

0.553

X31: Hierarchy

0.745

0.754

0.728

X32: Conformity

0.958

0.945

0.886

Table 5 (continued)

Effectiveness

Y1: Meeting of managerial performance standards

0.868

Y2: Overall managerial success

0.825

Y3: Comparisons to the person's managerial peers

0.849

Y4: Performance as a role model

0.909

Y5: Overall effectiveness as a manager

0.889

Goodness-of-fit indices for Complete Model

Chi-square

946.27

Degrees of freedom

584

Chi-square/degrees of freedom

1.62

RMSEA

0.670

(0.0589 , 0.0745)

90% Confidence Interval for RMSEA

CFI

0.975

IFI

0.975

39

TABLE 6

Cronbach Alpha Coefficients with Deleted Variables

Leadership Behaviors, Values, and Effectiveness

Leadership Roles

Innovator

Broker

Goal Orientation

Monitor

Facilitator

Mentor

Values

Integrity

Flexibility

Conformity

Effectiveness

Self

Direct Reports

Peers

Bosses

0.837

0.771

0.850

0.723

0.734

0.844

0.923

0.873

0.925

0.846

0.891

0.946

0.897

0.827

0.905

0.801

0.866

0.934

0.898

0.833

0.905

0.792

0.853

0.920

0.793

0.812

0.737

0.844

0.903

0.926

0.762

0.952

0.834

0.892

0.827

0.937

0.870

0.908

0.769

0.939

TABLE 7.

Final Regression Coefficients*

Step

Step 1

Step 2

Variable

Manager’s age

Manager’s gender

Manager’s education

Manager’s years in position

Manager’s years in government

R2

Innovator

Broker

Goal Orientation

Monitor

Facilitator

Mentor

R2

Delta R

Step 3

2

Self

Direct

Reports

Peers

Bosses

0.035

0.011

0.037

0.011

0.323

0.218

0.205

0.328

0.270

0.228

0.243

0.275

0.462

0.688

0.554

0.634

0.427

0.677

0.517

0.623

0.321

0.196

0.208

0.267

Integrity

Flexibility

Conformity

0.187

R2

0.491

0.743

0.597

0.661

0.029

0.056

0.042

0.027

Delta R

2

*Only the statistically significant paths at p ≤ 0.05 are shown.

Appendix A

Correlations for Self

Effectiveness Innovator

Broker

Goal Monitor Facilitator Mentor Integrity Flexibility Conformity

Orientation

Effectiveness

Innovator

Broker

Goal

Orientation

Monitor

Facilitator

Mentor

1.000

0.383

0.333

0.610

1.000

0.360

0.448

1.000

0.385

1.000

0.463

0.513

0.222

0.278

0.463

0.170

0.310

0.383

0.224

0.613

0.556

0.317

1.000

0.323

0.190

1.000

0.529 1.000

Integrity

Flexibility

Conformity

0.464

0.351

0.059*

0.243 0.230

0.282 0.314

-0.196 0.071*

0.510

0.507

0.186

0.429

0.435

0.443

0.369 0.311

0.554 0.571

0.062* 0.228

1.000

0.486

0.230

1.000

0.250

1.000

Note: Correlations not significant at 0.05 are marked *.

Correlations for Direct Reports

Effectiveness Innovator

Broker

Goal

Orientation

Monitor Facilitator

Mentor Integrity Flexibility Conformity

Effectiveness

Innovator

Broker

Goal

Orientation

Monitor

Facilitator

Mentor

1.000

0.694

0.634

0.730

1.000

0.691 1.000

0.669 0.623

1.000

0.520

0.688

0.508

0.556 0.466

0.742 0.657

0.353 0.190

0.752 1.000

0.701 0.505

0.414 0.139*

1.000

0.526

Integrity

Flexibility

Conformity

0.620

0.694

0.173

0.392 0.342

0.574 0.426

0.151 0.139*

0.542

0.607

0.312

0.449 0.642

0.659 0.746

0.163 0.109*

Note: Correlations not significant at 0.05 are marked *.

0.303

0.323

0.377

1.000

1.000

0.784

0.275

1.000

0.254

1.000

Correlations for Peers

Effectiveness Innovator

Effectiveness

Innovator

Broker

Goal

Orientation

Monitor

Facilitator

Mentor

Integrity

Flexibility

Conformity

Broker

Goal Monitor Facilitator Mentor Integrity Flexibility Conformity

Orientation

1.000

0.608

0.542

0.589

1.000

0.537

0.519

1.000

0.533

1.000

0.438

0.621

0.459

0.339

0.580

0.383

0.389

0.570

0.293

0.737

0.506

0.258

1.000

0.328

0.160

1.000

0.613 1.000

0.473

0.279 0.279

0.597

0.426 0.412

0.105* -0.058* 0.037*

0.477

0.483

0.187

0.404

0.275

0.376

0.393 0.384

0.657 0.699

0.143* 0.170

1.000

0.599

0.386

1.000

0.249

1.000

Note: Correlations not significant at 0.05 are marked *.

Correlations for Bosses

Effectiveness Innovator Broker

Goal

Orientation

Monitor Facilitator

Effectiveness

Innovator

Broker

Goal

Orientation

Monitor

Facilitator

Mentor

1.000

0.549

0.628

0.692

1.000

0.605 1.000

0.579 0.612

1.000

0.509

0.597

0.363

0.374 0.481

0.646 0.616

0.334 0.312

0.744 1.000

0.528 0.279

0.322 0.087*

Integrity

Flexibility

Conformity

0.647

0.594

0.157*

0.390 0.511

0.452 0.430

0.032* 0.215

0.606

0.472

0.232

Note: Correlations not significant at 0.05 are marked *.

42

0.517

0.224

0.278

1.000

0.605

Mentor Integrity Flexibility Conformity

1.000

0.479 0.377

0.689 0.704

0.075* 0.143*

1.000

0.652

0.193

1.000

0.188

1.000

Figure 1

The Competing Values Framework of Leadership Roles

FLEXIBILITY

People

Leadership

Mentor: Shows concern

for the individual needs

of subordinates.

Facilitator: Fosters

cohesion and teamwork.

Broker: Exerts upward

influence.

INTERNAL

FOCUS

EXTERNAL

FOCUS

Producer: Sees that the unit

meets stated goals.

Monitor: Monitors

compliance with rules.

Stability

Leadership

Adaptive

Leadership

Innovator: Searches for and

experiments with new ideas.

Coordinator: Coordinates

the workflow of the unit.

Director: Clarifies the unit’s goals

and directions.

CONTROL

Task

Leadership