to read this Article - American University Law Review

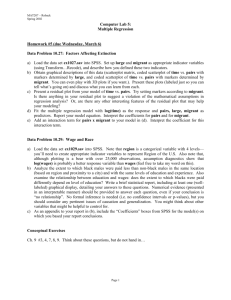

advertisement