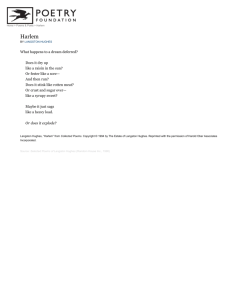

"Ain't You Heard"?: The Jazz Poetry of Langston Hughes

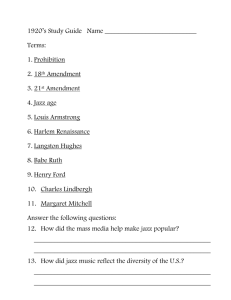

advertisement