Tourist satisfaction: A view from a mixed international

advertisement

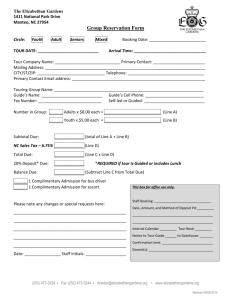

Journal of Vacation Marketing Volume 11 Number 4 Tourist satisfaction: A view from a mixed international guided package tour David Bowie* and Jui Chi Chang Received (in revised form): January 2005 Anonymously refereed paper *Department of Hospitality, Leisure and Tourism Management, Business School, Oxford Brookes University, Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK Tel: +44 (0)1865 483890; Fax: +44 (0)1865 483878; E-mail: decbowie@brookes.ac.uk David Bowie is a prinicipal lecturer and MSc programmes director at Oxford Brookes University. His main research interests are branding, distribution and marketing communication. Jui Chi Chang (Ricky) has a PhD from Oxford Brookes University and is now an associate professor in the Tourism Department at Providence University in Taiwan. His main research interests are consumer behaviour in the travel industry and package tour operation and management. ABSTRACT KEYWORDS: customer satisfaction, expectation, equity, hedonism, package tour, tour leader, tour operator This paper seeks to identify the variables that are related to customer satisfaction during a guided package tour service encounter, including the role of the tour leader and the service performance by suppliers – itinerary arrangements, auxiliary support and service delivery. Data were gathered through participant observation during a mixednationality tour of Scandinavian destinations. Expectations, customer on-tour attitude and behaviour and equity were identified as affecting customer satisfaction during the service encounter. Additionally, the consumption experience of hedonism and enjoyment (excitement factors) on the tour had a significant effect on customer satisfaction. Two primary sources of complaints were identified: first, the tour operator’s itinerary plan- ning and hotel selection (basic factors), and second, the tour leader’s competence (performance factor). The findings indicate that the tour leader is a significant determinant psychologically, spiritually and practically in influencing the success of the tour product. The result contributes to a better knowledge for the tour operator of tourism satisfaction in the international market for guided package tours. INTRODUCTION This study seeks to identify the variables which are related to customer satisfaction during an on-tour service encounter. Participant observation research was carried out to investigate the role of the tour leader and the service performance of suppliers in terms of itinerary management. The study develops a framework linking the role of the tour leader to the formation of customer satisfaction, and contributes towards a better knowledge of tourism satisfaction for tour operators and travel agencies. Numerous studies have focused on tourist satisfaction in tourism destinations.1 This study concentrates on customer satisfaction with the service performance of the tour operator, and other service suppliers, on a guided package tour. Customer expectation and satisfaction, past travel experiences (attitude and behaviour), equity, perceptions of hedonism and enjoyment and product and service performances are discussed in the literature review and then evaluated in the Journal of Vacation Marketing Vol. 11 No. 4, 2005, pp. 303–322 & SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks, CA, and New Delhi. www.sagepublications.com DOI: 10.1177/1356766705056628 Page 303 Tourist satisfaction findings. It is also revealed that the attribution of inequity is a crucial issue when considering customer satisfaction/dissatisfaction. The international tourist market has shifted from a seller’s market to a buyer’s market. The result is that clients are more likely to demand cheaper holidays and have an increased requirement for high standards of product design.2 The competitiveness of the marketplace and the increased expectations of customers have made service providers recognize the importance of customer service for future repeat and referral business.3 Jones and Sasser4 consider that the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty is by no means linear. In non-competitive marketplaces, a customer who is not satisfied has no alternative but to remain loyal. However, in highly competitive industries like tourism a highly satisfied customer has more alternatives and customer retention rates can be low. Since the tourism industry is a mature competitive market, it is more difficult to differentiate the tourism product significantly, but the key to differentiation may be service quality. NATURE OF GUIDED (ESCORTED) PACKAGE TOURS The package tour is a complex service product which is synthetic and involves the Figure 1 assembly of a multitude of components. The special characteristics of services seasonality, intangibility, perishability, inseparability, variability and simultaneous production and consumption apply to tourism. The package tour combines ‘hard’ tangible elements with a high proportion of ‘soft’ intangible service elements,5 and leads to a highly labourintensive product. The intangible nature of the package tour makes the tour operator heavily dependent upon the company’s image and word of mouth for generating repeat and recommended sales. Levitt6 stated that the most important thing to know about intangible products is that customers usually do not know what they are getting until they do not get it. However, guided package tours have become popular for specific market segments and represent a significant tourism market.7 Pre-arranged holiday products are vulnerable in a number of ways. Swarbrooke and Horner8 suggested that two negative factors which affect customer satisfaction on vacation are too much stress (see Figure 1), and insufficient arousal resulting in boredom and dissatisfaction. There is no guarantee that a package tour will not experience shortcomings and negative incidents which are out of the tour operator’s control. Moreover, the highly labour-intensive nature of a tour product makes the service encounter difficult to Sources of stress for tourists Transport delays Difficulties over money Unfamiliar customs and food Performance of service staff Page 304 Problems with foreign languages Tourist Failure of accommodation service Personal safety and health Relationships with fellow tourists Bowie and Chang manage and standardize. The inability to standardize service actions leads to an unpredictable quality of the service product. Service quality delivery is, therefore, based on a service-oriented approach in which the quality of front-line staff is essential for the successful business. In a sense, it might be argued customers’ satisfaction depends more upon front-line staff than upon management. TOUR LEADER The tour leader manages the group’s passage over a multi-day tour and has intense contact with the tour participants. This person may be an employee of the tour operator, a professional tour escort hired by the tour operator or a representative of the organization sponsoring the trip. The term ‘tour leader’ is also used to describe the tour manager, tour conductor, tour director or courier in Europe. Indeed, some tour companies prefer to call their tour leader a ‘tour guide’ to stress their employee’s sightseeing commentary skills.9 However, in practice the role of the tour guide is different from that of the tour leader. A tour guide is ‘one who conducts a tour’, or one with ‘a broadbased knowledge of a particular area whose primary duty is to inform’.10 To avoid confusion, the term ‘tour leader’ will be used in this paper to indicate the person who actually escorts the tour participants throughout their journey. The person conducting a tour needs a variety of skills and faces many challenges. The tour leader is a psychologist, diplomat, flight attendant, entertainer, news reporter, orator and even translator and miracle professional.11 To be successful at this job is not easy. Webster12 noted that keeping the tour participants happy and making certain that all services are provided as contracted are the main responsibilities of the ‘escort’. She also suggested ‘ten dos and ten don’ts’ for escorting a tour. To act professionally and demonstrate leadership, Stevens13 warned that a tour leader should never become personally involved with a tour member, since this may result in losing control of the tour. Undoubtedly, the tour leader is under considerable pressure during the service encounter. It requires patience and care to accomplish the task. Mancini14 offered strategies for managing a tour group, suggesting that the ‘tour manager’ must be fair; praise a tour group’s behaviour; exceed the client’s expectations; be firm when facing disruptive behaviour; encourage client ‘adulthood’; exercise leadership; and be flexible. Many empirical studies15 have demonstrated that the tour leader is a crucial factor in achieving customer satisfaction. Grönroos16 stated that it is the guide (tour leader) who sells the next tour. Mossberg17 studied a charter tour and suggested that a tour leader’s performance is a key factor in differentiating a tour operator from its competitors. The tour leader’s performance within the service encounter not only affects the company image, customer loyalty and word-of-mouth communication but can also be seen as a competitive factor. But customers’ satisfaction with the tour leader’s performance does not necessarily mean that customers will be satisfied with the tour operator.18 Mossberg19 also proposed that an enhanced understanding of what is happening during the service encounter between the tour leader and the customer is essential. THE SERVICE ENCOUNTER Service is a subjective concept and a complicated phenomenon. When selling a tour product, it usually also means selling intangible services.20 Quality of service is difficult to control before it is sold or consumed; its invisible and intangible nature make customers rely on the image of a firm for further purchases. Grönroos21 states that if an image is negative, any minor mistake will be considered as greater than it otherwise would be. The quality of service is decisive when the moment of truth is reached. Shostack22 defined the service encounter as ‘a period of time during which a consumer directly interacts with a service’. The service encounter, or the moment of truth, occurs when the customer assesses the service quality and his/ Page 305 Tourist satisfaction her satisfaction with the complex set of behaviours which have happened between the customer, the server and the service company.23 During service delivery, Gabbott and Hogg24 state that the quality of the service encounter involves two significant elements service personnel and the service setting. Three characteristics of service personnel directly affect consumers’ service experience:25 employees’ expertise, employees’ attitude and the demographic background of the employee. Bitner et al.26 consider that the contact employees who dissatisfy customers are often undertrained (which is due to a high turnover rate), suffer from job dissatisfaction or are underpaid with low levels of motivation. The service setting refers to the contact Figure 2 environment. Maslow and Mintz27 suggest that aesthetically pleasing physical surroundings and physical content can influence people’s mental state – a suggestion that has not lost resonance over time. Gabbott and Hogg28 consider that the service encounter involves five dimensions: time, physical proximity, participation, engagement and degree of customization. There are two unfavourable factors for travel service companies during the service encounter. When service involves multiple-encounter services and latent-encounter services, it is difficult to maintain the same level of satisfaction (see Figure 2). Secondly, Solomon et al.29 state that people are constantly changing their perspective of the service experience. People are social actors; they learn and adapt themselves through a series of social settings. The The sectors and critical incidents of a guided package tour Tour leader Guided package tour Hotel Hotel facilities Service attitude Location Restaurant Food quality Service attitude Coach Drivers attitude Seat arrangement Condition of coaches Shopping Shopping opportunities Amounts spent Optional tour Price of an optional tour Contents of optional tour Levels of satisfactio n Tour guide Service attitude Interpretation skills Attraction Time spent Levels of enjoyment Tour operator Others Page 306 Profession skills Service attitude Interactions Leadership Interactions Tipping Punctuality Unforeseeable events Weat her conditions Bowie and Chang level of satisfaction tends to be influenced easily by other people during multipleencounter services in a single transaction. EXPECTATION VERSUS SATISFACTION Expectation is the service that the customer anticipates. Santos30 stated that expectation can be seen as a pre-consumption attitude before the next purchase: it may involve experience, but need not. Davidow and Uttal31 proposed that customers’ expectations are formed by many uncontrollable factors these include previous experience with other companies and their advertising, customers’ psychological condition at the time of service delivery, customer background and values and the image of the purchased product. Miller32 constructed expectations in a hierarchical order and related them to different levels of satisfaction. He proposed the ‘zone of tolerance’ which is considered as an alternative comparison of standards and disconfirmation models. Miller categorized four types of expectation comparison standards by level of desire: the minimum tolerable level (the lower-level must be), the deserved level (should be), the expected level (will be) and the ideal level (the higher-level could be).33 The deserved level stems from what the consumer thinks is appropriate based on the cost and time invested and is more likely to be considered as a realistic expectation. The expected level of product performance is based on a customer’s objective calculation of the probability of performance. It is the most commonly used standard for comparison in customer dis/satisfaction research. The ideal level of product performance represents the optimal product performance a customer ideally would hope for. It may be based on previous product experiences, learning from advertisements and word-ofmouth communication. Zeithaml et al.34 stated that customer service expectations are built on complex considerations, including their own prepurchase beliefs and other people’s opinions. They suggested two levels of expectations – adequate and desired in service quality evaluations. The adequate level is the minimum level considered acceptable, and is what customers believe it could be. The desired level is the service the customers wish to receive: this is a mixture of what customers believe the level of performance can be and should be in other words, a mixture of Miller’s ideal and deserved level of expectations.35 Between the adequate and desired is the ‘zone of tolerance’, which represents a range of performance that the consumer considers acceptable. The ‘zone of tolerance’ is bounded by ‘the best customers can expect to get’ versus ‘the worst customers will accept as barely fulfilling their needs’. It appears that high expectations can frustrate satisfaction achievement. Furthermore, Bluel36 suggested a ‘zone of uncertainty’ to separate satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Woodruff et al.37 and Heskett et al.38 proposed a ‘zone of indifference’ regarding perceptions of performance. The concepts of ‘zone’ focus on customer uncertainty, which represents the position of satisfied (but not completely satisfied) customers who do not remain loyal to a firm. To produce an outcome of satisfaction, Pizam and Milman39 suggested the need to build modest or below-realistic expectations that are tolerable and meet customers’ investment value. Although this appears to be sensible in theory, in practice it is questionable since customers may not be motivated by unattractive or below-level promotion efforts in the first place among highly competitive and replaceable travel products. Perhaps several elements relating to expectation internal to the customer and external to the customer need to be taken into account. Internally, even similarly experienced tourists may have extremely different expectations due to cultural background. Externally, Santos40 considered that customers’ expectations are formed when they plan to go to a destination where they have never been and so they anticipate something about which they have no previous experience. It is natural for travellers to dream about having a good encounter rather than Page 307 Tourist satisfaction receiving a bad experience. However, from the supplier’s point of view the resultant expectations may be unclear and unpractical. Many theoretical frameworks have been introduced to measure customer satisfaction in hospitality and tourism. Oh and Parks41 concluded that of the nine theories which evaluate satisfaction it is expectancy disconfirmation that is most widely accepted among them. This theory, proposed by Oliver,42 suggested ‘positive disconfirmation’ when the perception of the actual received performance exceeds expectation, and ‘negative disconfirmation’ or a dissatisfaction occurrence when the perceived performance is worse than expected. However, Yüksel and Rimmington43 noted that expectancy disconfirmation theory has received theoretical and operational criticism. Measuring expectations prior to the service experience has its weaknesses. The expectation may not reflect reality, and may be based on a lack of information and unfair comparisons. Consumers’ prediction of performance might also be rather superficial and vague the customer may revise his/her expectation based on previous travel experience or on others’ opinions during the service encounter. Mazursky44 pointed out that the use of brand expectations has been questioned by researchers. Bowen45 supports Botterill’s46 view, with specific reference to tour packages, that satisfaction was not achieved by narrowing the gap between expectation and performance. Rather, tourists’ satisfaction could be achieved by the adaptation of the tourists themselves to unpredictable events. PERFORMANCE So, the measurement of customer satisfaction that compares expectation of performance and perception of performance during the service encounter on a tour may not reflect the real scenario. Swan and Trawick47 and Olshavsky and Miller48 suggested that performance only might be the crucial determinant of satisfaction for some items. Whipple and Thach49 believed that customers’ satisfaction should depend on the performance of suppliers, Page 308 especially for those who are first-time purchasers. Bowen,50 in a study of long-haul inclusive tours, suggested that six antecedents independently or in combination affected consumer satisfaction and dissatisfaction performance, expectation, disconfirmation, attribution, emotion and equity. In his participant observation, he found that the performance element was considered to have the greatest influence on tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the tour leader and the participants all have a significant influence on the tour performance. Geva and Goldman51 noted that the intense contact and constant interaction with participants gives the tour leader a positive advantage compared to a company (tour operator) that is not at the scene and is unable to defend itself. PREVIOUS EXPERIENCE AND ATTITUDE/BEHAVIOUR Extremely satisfied tourists might have great expectations of their next purchase. So comparing experienced travellers to those without similar experience, which group expects more or is more easily satisfied? Empirical studies show that previous experiences affect a person’s attitude and expectation towards the next purchase. Westbrook and Newman52 reported that people with previous travel experience developed more moderate expectations than did people without previous travel experience. They also pointed out that people with extensive travel experiences tended to develop realistic expectations and showed greater satisfaction ratings than did people without experience. Whipple and Thach53 concluded that ‘experienced participants gave consistently higher expectation and performance ratings for services. . . inexperienced travellers, conversely, expected more from the special events concert and dining’. Woodruff et al.54 introduced an ‘experience-based model’ which emphasized the consumers’ experience with an evoked set of brands as determinants of satisfaction. The model indicated that consumers’ experience Bowie and Chang should be taken into account when evaluating their satisfaction during service encounters. So far, however, there is limited evidence to indicate that there is a positive relationship between experience and satisfaction. Tourist value is associated with the holiday experience at a destination.55 Zeithaml56 defines perceived value as ‘the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on a perception of what is received and what is given’. Many researchers believe that people change their behaviour during a vacation. Carr57 considers that personal motivations for taking a vacation and tourist culture have an impact on tourist behaviour. They become more liberated and less restrained than when staying at home. This trait of tourist behaviour might be influenced by the holiday atmosphere,58 but it is believed that personal characteristics in terms of norms and values also play an important part in influencing this kind of behaviour.59 It has been confirmed that equitable treatment during the process of consumption among tourists is an important factor. EQUITY Equity concepts are known to influence satisfaction directly.60 Therefore, equitable treatment during the process of consumption among consumers needs to be paid more attention. The judgement of fairness is very individualistic and diverse because of personal value judgements and cultural background; it involves idiosyncratic tangible and intangible elements.61 Oliver62 stated that: ‘many equity norms are held as passive expectation, as in fair play in sports and gentlemen’s agreements more generally. Thus, feelings of equity may not be processed unless these norms are violated.’ Francken and Van Raaij63 regarded the attribution of inequality as a significant factor in determining satisfaction/dissatisfaction. Social equality theory deals with interchange relationships between individual input (cost) and output (benefit). Oliver and DeSarbo64 proposed the ‘equity model’ of satisfaction which suggested that the customer would be satisfied when the amount of input to outcome ratio is perceived as impartial and fair. In guided package tours there are many interactions and so inputs and outcomes between a tour leader and tour members. In guiding a package tour, Webster65 suggested that the tour leader should not have favourites and should try to treat every group member equally. HEDONISM AND ENJOYMENT Hunt66 stated that satisfaction is not the pleasurable expression of a consumption experience but an evaluation of product performance. Consumption emotion during product usage is distinguishable from satisfaction. Joy, anger and fear are expressions of emotional experience.67 With the study of consumption experience in playing video games, Holbrook et al.68 suggested that it is quite reasonable to expect that one’s emotional responses to playful consumption in a game should depend on performance. The success of the game should reinforce one’s feeling of pleasure, arousal and dominance. Unger and Kernan69 considered that the consumption experience of satisfaction, enjoyment, fun and other hedonic aspects have been widely accepted as the essence of play and other leisure activities. Holbrook and Hirschman70 stated that consumer behaviour includes hedonic elements of fun, feelings and fantasies that ought to be examined in their own right. Hedonic value is a more subjective and personal feeling and results in more fun and playfulness compared with its utilitarian counterpart.71 The enjoyment perceived during the travel encounter is of increasing concern to holidaymakers and can be viewed as part of the contribution towards the satisfaction with a complete consumption experience. Consciousness of enjoyment itself is a significant hedonic benefit provided through shopping activities72 and travel experiences. Babin et al.73 emphasized that recreational shoppers are likely to expect high levels of hedonic value. Many aspects of travel experience, such as gift shopping, cui- Page 309 Tourist satisfaction sine tasting, viewing scenic beauty and relaxation were perceived as pleasurable by tourists. STUDY METHOD The primary research method involved participant observation. Satisfaction is an emotional response and changes frequently at multiple levels during service encounters throughout a package tour (see Figure 2). The complexity of the service in a tour product and the perceptions of customers toward those services are difficult to unravel unless the consumption experience is actually observed. For example, observation at the hotel front desk during and after a tour group’s check-in can identify significant incidents relating to the problems that customers encounter and the service personnel’s response. Participant observation can illuminate the details regarding human existence, which can then be used to examine critically and further develop hypotheses and theories. When a phenomenon is imprecise and impenetrable to outsiders, or the research problem is imbued with human meanings and interactions, the researcher needs to investigate the issue by gaining access to the internal aspects of the phenomenon and exploring deeper meanings, which can be discovered by observing the reality.74 The participant observation approach allows a researcher to interact with those they study and minimize the distance between the researcher and those being researched. Gabbott and Hogg75 suggest that, in reality, it is difficult to know travellers’ real needs or travel motives indeed, travellers may not be aware of their motives (the ‘hidden’ motive), or they may not tell the truth. Veal76 confirmed that participant observation provides an insight into the real world and uncovers the complexity of social settings. It is a key method to research particular phenomena and is commonly used in leisure and tourism elements. Participant observation has been utilized in guided tours in a range of different contexts.77 In a study of the relationships between client expectations and satisfaction in Page 310 river-rafting trips, Arnould and Price78 found that participant observation data enrich the interpretation of qualitative results. Ryan79 stated that in the area of tourism research, direct interaction with respondents by the researcher playing a real part rather than simply acting as a detached observer also generates rich and significant data. Seaton80 carried out an exploratory study of a guided tour party, which involved a three-day tour of European First World War battlefields, using the participant observation technique; his findings confirmed the use and benefits of participant and unobtrusive observation in tourism satisfaction research. Seaton81 suggests that the method of observation in a closed-field tourism event offers real opportunities in research. He also stated that many researchers support the view that participant observation is a valid research methodology for conducting tourism research; in another study, Bowen82 confirmed that participant observation makes a significant contribution to understanding tour operation management. The guided package tour The researcher, using a combination of convenience and purposive selection methods, chose a guided package tour to Scandinavia because of the destination’s image as a remote and exotic holiday; most participants later described it as a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ experience. The tour operator was selected because it was a major international company with extensive distribution channels. Participants booked the tour from a wide variety of different countries. The nationalities included Americans, Australians, Britons, Koreans, Kuwaitis and Singaporeans. The product was a mid-market, midprice tour visiting three countries Denmark, Norway and Sweden over a period of 12 days in the month of July, starting in Copenhagen. The tour comprised two groups (A and B) who stayed in the same hotels and had mostly the same itinerary. The researcher joined Group B, which had 43 participants (13 couples, eight solos and two families Bowie and Chang totalling nine people). There were 24 females and 19 males (including the researcher). While most of the couple participants were aged between 40 and 60, the solo participants, most of whom were female, tended to be younger but over 30. Both the couples and solo participants had considerable prior travel experience. Many of the participants had used the tour operator before. The tour leader for Group B was a 26year-old Dutch female with only a few months’ work experience in the travel industry. Group A had a very experienced male tour leader. Along with the two tour leaders, three tourist guides were arranged for local interpretation in different destinations for both groups. Gathering data The participant observation started at Copenhagen airport on the first day and ended there on the last day. Observations were conducted throughout the entire tour experience. A male Chinese researcher carried out the participant observation; most conversations and observations took place during breakfast, dinner, free leisure time and on a coach. The setting of a coach interior provides a strong physical and psychological directive for interaction,83 and this physical proximity encourages interaction. The researcher was able to interact with different tour members on the coach, although the inflexibility of the seating arrangements did create some constraints. There was no difficulty for the researcher in approaching solos and family members, but some of the couples tended to sit alone and walk together – this restricted the researcher from having conversations with them. On the second day of the tour the tour leader introduced each group member and their nationality, which helped the tour members become acquainted with each other. Most group members seemed interested in discussing their experiences with each other. Ethical considerations appear when research involves human participants – the conflict between the ‘right to know’ and the participants’ ‘right to privacy, dignity and self-determination’. Rossman and Rallis84 considered that ethical dilemmas were not solvable but could be reasoned through moral principle; a researcher may not agree with the prevailing dominant principle but he or she must be able to explain the reason behind it. Judd et al.85 believed that participant observation is clearly not free of ethical problems; but the people who are studied might be given a more equal voice if the research is recoding rather than manipulating events, and listening rather than forcing people into participation. Serious thought was given to the ethical issue before carrying out this participant observation research. The research team believed that an observational study of naturally occurring behaviour in a public space, without any manipulation of events, was acceptable since it did not expose participants to physical or mental stress or invade their privacy in any significant degree. The collected data, including conversations and observation of participants’ actions, could be coded anonymously, and reflection upon the customers’ needs and expectations from the package tour could be viewed as a social phenomenon. It was judged that a covert participant approach was unlikely to affect the privacy of participants, so participants were not told that they were being observed.86 This avoided unnecessary bias since the researcher was one of the group participants and was no different from the other travellers. He paid the same fee for joining the tour, and the tour operator and company employees were not aware of this research. The researcher tried to maintain a neutral role during conversations with group members and avoided forced or leading questions throughout the tour. Descriptive observation was recorded in fieldnotes written in Chinese on a regular basis. This enabled accurate records of conversations and incidents to be written in private. Cultural differences did not hinder the participant observation. Modified grounded theory87 was applied to generate theory. An intensive data analysis was processed to discover the cultural patterns of the social situation that emerged during the observation. Fieldnotes were ana- Page 311 Tourist satisfaction lysed using domain analysis, which is a systematic examination of content and the development of categories.88 The first step in the analysis was to describe each group member’s expectation and the actual travel experience which they encountered on the tour. The second step was to identify customers’ emotional feelings such as complaints, enjoyment and levels of dis/satisfaction based on their experiences with the service encounters and their interactions with other group members. The third step was to categorize the critical incidents in each sector of the guided package tour which led to complaints, enjoyment and levels of dis/satisfaction. Critical incidents were identified within the general framework of Wang et al.89 (see Figure 2). Based on the critical incidents, the final step was to identify the variables that related to customer dis/satisfaction. This is depicted in Figure 3. This study focused on the observations of the original experiences of tour participants during the tour only. An important part of this study is the identification of those variables that influence customers’ satisfaction which emerged during the participant- Figure 3 observation. However, it should be noted that this study evaluates rather than measures customers’ satisfaction. The participating group members were international tourists and most of them spoke English. Some nuances of language might not have been observed due to the accents and second languages spoken. Less familiarity with cultures, and also cultural differences, among group members may have in minor ways affected the researcher’s collection of wider opinions and interpretation of nuance. However, these limitations were deemed to be relatively minor restrictions and thought not to have affected the accuracy of data analysis. Other limitations may also have occurred. First, the data collection primarily focused on the stories of the participant group members about their experiences, whilst the tour leader’s perspective was not investigated in depth. Second, the tour operator organized two groups (A and B) at the same time with the same itinerary. Participants’ dis/satisfaction in Group B (see below) might have been different if they had not been able to compare their experiences with Group A. The study’s approach Participant observation Modified grounded theory Emotional feeling Performance of customers Performance of suppliers in each sectors Domain analysis Theories: Performance, equity, expectation, disconfirmation, attribution, emotion Critical incidents Variables related to customer satisfaction Page 312 Bowie and Chang FINDINGS A number of key findings emerged. First, prior expectations, attitude and behaviour and equity were found to have significantly influenced customers’ enjoyment and satisfaction on the tour. Second, there were two major sources of complaints – the tour operator’s arrangements (hotel selection and itinerary) and the tour leader’s competence. Third, couples seemed to have more enjoyment and fewer complaints than the solo participants – indeed the British, Irish and Australian couples did not show especial emotional reactions to problems and did not complain. Finally, the results indicated that the tour leader is the significant determinant – psychologically, spiritually and practically – affecting the success of the tour product. Expectations The findings suggested that the customer’s degree of expectation is strongly related to past travel experience and the perception of package tour products. Past travel experience can be classified into past guided package tour experiences – either with the same or a different tour operator – and non-guided package tour experiences. Mancini90 stated that tour participants bring high expectations – for example, they expect that every meal in the tour will be perfect – and so their expectations are unrealistic. In this study participants who had organized their own vacations, and for whom this was the first time they had joined a group tour, tended to have low expectations. In contrast, those who had travelled with the same tour operator before had high expectations; they tended to develop an ideal level of expectation which was based on their previous experiences.91 However, since all the participants were visiting Scandinavia for the first time, some of the expectations about the tour product were not explicit – except their expectations of the tour leader’s role. ‘This is my first time joining a group tour and I don’t expect too much.’ JJ (American, who has travelled a lot with his wife). ‘Why do you join the group tour if you don’t expect too much? I always expect more.’ AW (American woman, Day 10). AI, an Australian, asked the tour leader for optional tours on Day 1 and said that she would like to join them all. She had very high expectations of all the optional tours (from previous experience) – she joined all of them and was happy with the results. Most of the participants with previous travel experience expected the tour leader would ‘do a good job’ during the tour. This high expectation was based on their previous positive experiences with tour leaders. The findings showed that customers’ expectations were closely related to past personal experiences – good experiences resulted in higher expectations; negative experiences resulted in lower expectations. However, once the tour had started the participants’ actual expectations of Group B’s tour leader were affected by comparison with Group A’s tour leader. In one sense, their ‘zone of tolerance’ narrowed and their adequate level of expectations shifted higher. This comparison may have moved the perceptions of performance down towards the ‘zone of indifference’. Attitude and behaviour At the beginning of the tour, participants who were joining a group tour for the first time and had negative thoughts, along with those who had had unpleasant previous experiences, were uncertain and lacked confidence in the product. However, the performance of the tour leader and interactions with other group participants either confirmed their fears or altered their opinion (positively). Indeed, the participants’ enjoyment of the tour was based more on numerous ‘moments of truth’ rather than any prejudicial pre-tour attitudes. Attitudes were also influenced by the positive/negative views of other participants. Under certain circumstances, tourists’ behaviour was changed by either imitation, interaction or the setting. For example, at the end of the city tour (Day 10), the tour guide was standing at the front door of the coach waiting for her tips. AI, an experienced traveller who had joined Page 313 Tourist satisfaction most of the optional tours, said ‘There is no need to tip the tour guide.’ Not many participants tipped her – despite encouragement in the tour booklet and suggestions from the overall tour leader. The coach had two doors and some group members got off the coach through the back door to avoid the embarrassment of not tipping. A positive interpersonal relationship is vital for travellers during the journey. The study group was composed of numerous couples, several solo travellers and two families from all over the world. The couples seemed to have more interactions with other couples and tended to enjoy each other’s companionship. Most of the solo participants did not seem to be enjoying the companionship of their tour members very much (see Table 1). Several causes for this were apparent: their cultural background, personality, the reduced chances of interaction with the couples and purpose of travel. This study showed that the couples and family groups seemed more satisfied and complained less than the solo participants but there is certainly scope for confirmation of such a finding in a further study. Equity The itinerary involved many days of long driving by coach through rural areas. The tour leader had requested ‘seat rotation’ to enable each group participant to have an equal opportunity of sitting in the front. However, many tour participants were confused by this, and whilst some participants did rotate others did not; this resulted in conflict between group members, which was not resolved by the tour leader. Besides seat rotation, several other issues concerned the participants, such as the tour leader’s lack of experience, the fee paid for the tour, the extra room fee for solo participants and the contents of optional tours. The following are extracts from the researcher’s notes. ‘In the morning a quarrel occurred. AI complained to the tour leader that some group participants always occupied the front seat. The tour leader was quiet. AAB fought back and said to AI: ‘‘Lady, why don’t you just shut up.’’ (Day 10)’ ‘AJ, an American, couldn’t sleep in a single-size bed. She complained and said ‘‘it is unfair, I have paid an extra fee for the hotel room – how come I only get a single-sized bed in my room?’’ (Day 3)’ ‘SG from Singapore said: ‘‘I feel that some optional tours are focusing on food which is only suitable for Western people. I feel that it is not worth joining them – it is boring and a waste of time because these people tend to spend long hours drinking wine.’’ (Day 2)’ ‘The comparison between Group A and Group B’s tour leaders was noted when both groups stayed in the same hotels. Two Taiwanese tour participants in Table 1: Solo participants and their problems Character Divorced woman – AC Incident Had lots of travel experience and had very high expectation of both the tour operator and the tour leader; fought with a group member by accusing him of not rotating his seat; was mad at a woman who was sitting next to her on the coach for speaking too much; she disliked a lady who complained too much. Single woman – AJ Interrupted others’ conversation without any hesitating; could not find partners to go to the pub; annoyed tour members and gave the tour leader lots of headaches by persistent requests for a queen-size bed. Married woman travelling Lost her luggage for many days; complained that the food was without alone – KW enough vegetables; was not pleased with the tour leader; could not stand the roommate for either making too much noise or being too dependent. Page 314 Bowie and Chang Group A told me that Group B are unhappy with their tour leader and they considered Group A tour leader to be much more interesting and stimulating. (Day 4)’ Enjoyment Undoubtedly, travellers hope that they will have an enjoyable holiday. Indeed, enjoyment influences the level of customer dis/ satisfaction, especially through memorable incidents – both positive and negative. Many studies have shown that relaxation and appreciating the local scenery are important for travellers.92 This study demonstrated that most group participants prefer to rise late, dislike a rushed itinerary and want the opportunity to explore local areas for themselves. Many participants suggested that the itinerary of the trip should be altered and the coach should stop at small towns instead of at restaurants next to gas stations for breaks. En route, potentially interesting scenic visits and contact with local culture were frequently unenjoyable, due to the limited time available because of itinerary constraints. In fact, a contradiction always existed between tour operators and their customers regarding the tight schedule. Whilst bars were favourite places for Western people, the Asians were less interested in drinking alcohol in bars. Most of the tour participants regarded shopping and taking photos as significant and enjoyable activities on the tour. Purchasing souvenirs and gifts for family and friends and showing photos are a key part of the post-tour enjoyment – shopping experiences can create value by providing enjoyment.93 However, the tour operator arranged accommodation too far away from city centres and this inhibited participants’ opportunity for shopping and nightlife activities. Tour leaders’ performance: Professional skills and unforeseeable events The tour leader came under special pressure from tour participants when unforeseeable events occurred. The various ethnic groups, who had different cultural backgrounds and different attitudes, had different approaches to resolving difficulties, and this created complications for the tour leader. Clearly, many unforeseeable factors can affect customer enjoyment and satisfaction, especially the performance of the tour leader under pressure. This study identified two dimensions – external factors and internal factors – which put the tour leader under pressure. The external factors included delayed flights, hotels’ labour shortage, bad weather, lost luggage, illness, non-punctuality such as group members arriving late for coach departures, overcrowding in restaurants, tour members’ attitudes such as breaking the rules and selfishness and language obstacles. Among those variables, participants’ personality was found to be the key factor involved with the unforeseeable events. All of these events occurred and influenced dis/satisfaction to a certain degree, but they were out of the tour leader’s control. These events were noted by the reseacher. ‘Following a city tour there was some free time for leisure before the journey continued. When it was time for the coach to depart, AC was missing and no one knew where she was. One hour later she came back and the tour leader wanted her to apologize to all the group members. AC just said: ‘‘I lost direction’’, but other tour participants were upset. (Day 4)’ ‘KW, a married Korean woman from the USA, took the tour alone because of marital problems. The airline lost her luggage and did not return her suitcases for several days. This put her in an extremely bad mood and totally ruined her holiday – even though the tour leader spent a lot of time calling the airline on her behalf.’ Internal factors primarily involved the tour leader’s professional skills. The findings revealed that the tour leader’s character, personal experience and knowledge were most important. The lack of experience of the Group B tour leader and the comparison with the Group A tour leader made the Page 315 Tourist satisfaction Group B tour leader a target for criticism. However, without such a comparison (i.e. if there was only one coach on the tour), Group B participants might have had different opinions/perceptions of their tour leader. Some evidence demonstrating the tour leader’s shortcomings included: • unfamiliarity with the local language – the tour leader could not help customers to order food; • non-familiarity with some hotels arranged for the journey; • lack of enthusiasm to help tour participants under certain circumstances; • unwillingness to hear advice; • inadequate knowledge in interpretation; • inadequate communication skills, which resulted in misunderstandings with some of the group members. A number of tour participants chose the tour operator because of their favourable impression of tour leader performance on previous tours. The Group B tour leader admitted that she had only a few months’ guiding experience. Although she actually did make a considerable effort on behalf of participants, the comparison with the experienced tour leader put her in a difficult situation. This finding showed that an inexperienced tour leader could easily jeopardize customers’ satisfaction because of a lack of core knowledge and the inability to explain local Scandinavian culture, customs and history. Simply providing a good service without giving detailed explanations of the locality was not satisfactory for some participants. Interpersonal communication skills were another significant factor for success, especially when providing services for international tourists. Participants’ complaints with regard to the Group B tour leader included: • did not control noisy participants when travelling on the coach; • forgot to pick up a participant at the airport! • lack of knowledge and inexperienced; • did not take group members out to local bars and attractions; Page 316 • talked too much; • did not prevent disagreements between participants, for example forgetting to remind participants to rotate their seats. Some of the complaints stemmed from the fact that the tour leader had personal favourites. Indeed, the performance of the tour leader could have been improved if she had paid more attention to the opinions of the tour participants. These shortcomings influenced customer enjoyment and satisfaction in different degrees, either directly or indirectly. However, not all the tour participants were upset by these shortcomings. Complaints One cause of dissatisfaction toward the tour operator was the intense itinerary and many days of long driving by coach especially the whole day driving on Day 11. However, the findings showed that tour members complained more about the hotel services and the tour leader than other services. This might indicate a correlation between the length of contact time and the number of complaints. Participants tended to expect better-quality hotel facilities and services, but complained when the services were inconsistent or unsatisfactory. In fact, customers’ complaints about the service of hotels seemed to be understandable; they did not overexaggerate their demands or require high standards of service quality or facilities. Their complaints could be avoided if service providers were thoughtful when providing services. Complaints were noted by the researcher. ‘During a hotel check-in, BJW, a couple who were both slightly disabled, were upset by the hotel service. The hotel had no elevators and no service personnel who could help them to carry their luggage to the hotel room. (Day 1)’ ‘The hotel on the first night and the last night was situated next to a railway, which upset many participants. One participant complained that this was an absolutely unforgivable mistake. (Day 1)’ Bowie and Chang ‘During lunchtime, AI, AJ and AC sat together. AJ from America complained that she couldn’t sleep and fell out of the bed all the time. She said ‘‘. . .the single size bed is too small for me to sleep in.’’ AJ approached the tour leader many times to request a double bedroom. One day before the check-in to the hotel she again argued with the tour leader. The tour leader said, ‘‘. . . our conversation is over’’ (Day 2, 3)’ DISCUSSION It might seem that there is no way in which a tour operator could satisfy each individual need during a service encounter unless dealing with a luxury/small tour with a homogeneous group. Although customers’ expectations are strongly related to past travel experiences, their expectations can be unrealistic when on the tour. Too many unforeseeable factors affect the service delivery not to mention the complex background of a mixed group of international tourists. Cultural differences and individual personality also influence the satisfaction of customers. Moreover, the tour leader’s performance seems difficult to standardize. It is true that an experienced tour leader should be able to foresee problems and solve them before they occur. To avoid misunderstanding, perhaps the tour operator should provide customers with a list of the ‘dos and don’ts’ that might allow a tour to be more successful. If this is not practical, an introduction at the beginning of a tour by the tour leader so as to identify the nature of the product and local culture is essential. Psychological build-up and good communication with customers are important for providing a successful service. However, whilst the work that the tour operator or tour leader has done on behalf of customers may be very good, it may not entirely influence customers’ total satisfaction. In short, customers’ satisfaction is composed of hard tangible elements and soft intangible service. It is the combination of, on the one hand, the service performance of the tour leader and the tour operator and, on the other, the customers’ anticipation and perceptions of the vacation, their expectations prior to the tour, their attitudes and behaviour (past travel experience) and their perceptions of equity and unforeseeable events during service encounters. The tour leader coordinates the successful delivery of the tour operator’s product provided by a multiplicity of suppliers. Customers’ satisfaction will be developed through confidence in the product and the leadership of the tour leader (see Figure 4). Pond94 discovered that ‘condescending’, substandard behaviour toward groups is rampant throughout the industry. He considered that leadership and social skills are significant in the guiding experience. Lopez95 considered that leadership styles of tour leaders during a tour are related to customer satisfaction. Lopez suggested that in the initial period of the tour the group members are more satisfied with the tour quality under authoritarian leadership. By contrast, in the latter part of the tour the group members are more satisfied under democratic leadership. As a result, clear Formation of customer satisfaction – The role of the tour leader Hotels Restaurants Hard tangible elements Confidence Tour operator Tour leader Expectation Satisfaction Leadership Coach Attractions Figure 4 Equity Customer behaviour Unforeseeable events Experience Soft intangible service Page 317 Tourist satisfaction structuring of orientation sessions for travellers may be very important at the initial stage of the tour, and may enhance the confidence of the travellers. CONCLUSION Whilst looking at customer satisfaction, most researchers use a quantitative research technique of questionnaires to measure the level of customer dis/satisfaction, using those determinants which researchers have assumed will have an impact on customer satisfaction. In order to look with insight into the reality of customer dis/satisfaction, this study used participant observation to collect first-hand, rich information. It could be argued that conducting only one participant observation was not enough to discover the whole picture of how travellers were satisfied. In addition, the collected data might be biased due to the researcher’s personal subjectivity even though the researcher took great care to avoid such a situation. Post-tour telephone interviews were considered in order to overcome the limitations of participant observation study. However, the researcher faced the challenge of accessibility in engaging in international telephone interviews: the tour participants were from different countries, and were not told that they were being observed. Customer satisfaction is a pivotal concern for tour operators to generate future business. This study identified the following important variables, which were related to customer satisfaction during a mixed international guided package tour: expectation, customer on-tour attitude and behaviour, the perception of equity and the performance of the tour leader. The study also developed a framework (see Figure 4) for tour operators in providing customer satisfaction. The proposed framework suggested the importance of the tour leader’s leadership skills and emphasized the importance of tour leaders’ performance but ignored the service attitude of tour leaders, such as personal service attention. In fact, international tourists from different cultural backgrounds might evaluate tour leaders’ service attitude as more important Page 318 than their performance skills. Asian tourists demand much more personalized and customer-oriented service.96 Since culture symbolizes patterns of behaviour associated with a particular group of people,97 different ethnic groups might require different leadership styles and service attention. It was impossible to specify what kinds of leadership styles might be appropriate for a tour leader for a mixed international guided package tour. A further study would be useful to find out the service characteristics/leadership styles of tour leaders from different ethnic groups or nationalities, and which style(s) would fit best in a mixed international guided tour. This study has hinted at the different needs for satisfaction in terms of ethnic groups. Mixed-culture international group tours will almost certainly increase in the future. To understand better what makes tourists dissatisfied or complain about a specific tourist experience, further studies should seek to identify the needs of specific ethnic groups. Moreover, it seems that companionship is a crucial factor in assessing customer satisfaction; so the study of solo/ couple/family travel segments in the package tour is also recommended for further research. REFERENCES (1) Pizam, A., Neumann, Y. and Reichel, A. (1978) ‘Dimensions of Tourist Satisfaction with a Destination Area’, Annals of Tourism Research, 5(3): 314–22; Beard, J. G. and Ragheb, M. G. (1980) ‘Measuring Leisure Satisfaction’, Journal of Leisure Research, 12(1): 20–33; Lounsbury, J. W. and Hoopes, L. L. (1985) ‘An Investigation of Factors Associated with Vacation Satisfaction’, Journal of Leisure Research, 17(1): 1–13; Duke, C. R. and Persia, M. A. (1996) ‘Consumer-Defined Dimensions Female Escorted Tour Industry Segment: Expectations, Satisfaction, and Importance’, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 5(1/2): 77–99; Weber, K. (1997) ‘The Assessment of Tourist Satisfaction Using the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory: A Study of the German Travel Marketing in Australia’, Pacific Tourism Review, 1(1): 35–45. Bowie and Chang (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) (19) (20) Moutinho, L. (ed.) (2000) Strategic Management in Tourism. New York: CABI Publishing. Harris, E. K. (1996) Customer Service: A Practical Approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Jones, T. O. and Sasser, W. E. Jr (1995) ‘Why Satisfied Customers Defect’, Harvard Business Review, 73(6): 88–99. Westwood, S. H., Morgan, N., Pritchard, A. and Ineson, E. M. (1999) ‘Branding the Package Holiday – The Role and Significance of Brands for UK Air Tour Operators’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 5(3): 238–52. Levitt, T. (1981) ‘Marketing Intangible Products and Product Intangibles’, Harvard Business Review, 59(3): 94–102. Mancini, M. (1996) Conducting Tours, 2nd edn. New York: Delmar Publishers. Swarbrooke, J. and Horner, S. (1999) Consumer Behaviour in Tourism. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. Mancini, ref. 7 above. Pond, K. L. (1993) The Professional Guide: Dynamics of Tour Guiding. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Mancini, ref. 7 above. Webster, S. (1993) Group Travel Operating Procedures, 2nd edn. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Stevens, L. (1990) Guide to Starting and Operating a Successful Travel Agency, 3rd edn. New York: Delmar Publishers. Mancini, ref. 7 above. Lopez, E. M. (1980) ‘The Effect of Leadership Style on Satisfaction Levels of Tour Quality’, Journal of Travel Research, 18(4): 20–3; Quiroga, I. (1990) ‘Characteristics of Package Tours in Europe’, Annals of Tourism Research, 17(2): 185–207; Geva, A. and Goldman, A. (1991) ‘Satisfaction Measurement in Guided Tours’, Annals of Tourism Research, 18(2): 177–212; Mossberg, L. L. (1995) ‘Tour Leaders and Their Importance in Charter Tours’, Tourism Management, 16(6): 437–45. Grönroos, C. (1978) ‘A Service Oriented Approach to Marketing of Services’, European Journal of Marketing, 12(3): 588–601. Mossberg, ref. 15 above. Geva and Goldman, ref. 15 above. Mossberg, ref. 15 above. Shostack, L. (1977) ‘Breaking Free from Product Marketing’, Journal of Marketing, 41(April): 73–80. (21) Grönroos, C. (1990) Service Management and Marketing – Managing Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. (22) Shostack, G. L. (1985) ‘Planning the Service Encounter’, in Czepiel, J. A., Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C. F. and Gutman, E. G. (eds) The Service Encounter – Managing Employee/Customer Interaction in Service Businesses, pp. 243–54. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. (23) Bateson, J. (1985) ‘Perceived Control and the Service Encounter’, in Czepiel, J., Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C. F. and Gutman, E. G. (eds) The Service Encounter – Managing Employee/Customer Interaction in Service Businesses, pp. 67–82. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. (24) Gabbott, M. and Hogg, G. (1998) Consumers and Services. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. (25) Czepiel, J. A., Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C. F. and Gutman, E. G. (eds) (1985) The Service Encounter – Managing Employee/ Customer Interaction in Service Businesses. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. (26) Bitner, M. J., Boons, B. M. and Tetreault, M. (1990) ‘The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favourable and Unfavourable Incidents’, Journal of Marketing, 54(January): 71–84. (27) Maslow, A. H. and Mintz, N. (1953) ‘Effects of Aesthetic Surroundings’, Journal of Psychology, 41(1): 247–54. (28) Gabbott and Hogg, ref. 24 above. (29) Solomon, M., Surprenant, C., Czepiel, J. A. and Gutman, E. (1985) ‘A Role of Theory Perspective on Dyadic Interactions: The Service Encounter’, Journal of Marketing, 49(Winter): 99–111. (30) Santos, J. (1998) ‘The Role of Tour Operators’ Promotional Material in the Formation of Destination Image and Consumer Expectations: The Case of the People’s Republic of China’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 4(3): 282–97. (31) Davidow, W. H. and Uttal, B. (1989) ‘Service Companies: Focus or Falter’, Harvard Business Review, July–August: 77–85. (32) ‘Miller, J. A. (1977) ‘Studying Satisfaction, Modifying Models, Inciting Expectations, Posing Problems and Making Meaningful Measurements’, in Hunt, H. K. (ed.) Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Page 319 Tourist satisfaction (33) (34) (35) (36) (37) (38) (39) (40) (41) (42) (43) (44) (45) Page 320 Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction, pp. 72–91. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. Miller, ref. 32 above. Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L. and Parasuraman, A. (1993) ‘The Nature and Determinants of Customer Expectations of Service’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(1): 1–12. Miller, ref. 32 above; Ekinci, Y., Riley, M. and Chen, J. S. (2001) ‘A Review of Comparison Standards Used in Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction Studies: Some Emerging Issues for Hospitality and Tourism Research’, in Mazanec, J. A., Crouch, G. I., Brent Ritchie, J. R. and Woodside, A. G. (eds) Consumer Psychology of Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure, pp. 321–32. New York: CABI Publishing. Bluel, B. (1990) ‘Commentary: Customer Dissatisfaction and the Zone of Uncertainty’, Journal of Services Marketing, 4(1): 49–52. Woodruff, R. B., Cadotte, E. R. and Jenkins, R. L. (1983) ‘Modeling Consumer Satisfaction Processed Using ExperienceBased Norms’, Journal of Marketing Research, 20(August): 296–304. Heskett, J. L., Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, W. E. Jr and Schlesinger, L. A. (1994) ‘Putting the Service Profit Chain to Work’, Harvard Business Review: 164–74. Pizam, A. and Milman, A. (1993) ‘Predicting Satisfaction Among First Time Visitors to a Destination by Using the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 12: 197–209. Santos, ref. 30 above. Oh, H. and Parks, S. C. (1997) ‘Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality: A Critical Review of the Literature and Research Implications for the Hospitality Industry’, Hospitality Research Journal, 20(3): 35–64. Oliver, R. L. (1980) ‘A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions’, Journal of Marketing Research, 17: 460–9. Yüksel, A. and Rimmington, M. (1998) ‘Customer-Satisfaction Measurement Performance Counts’, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 39(6): 60–70. Mazursky, D. (1989) ‘Past Experience and Future Tourism Decisions’, Annals of Tourism Research, 16(3): 333–44. Bowen, D. (2001) ‘Antecedents of Consu- (46) (47) (48) (49) (50) (51) (52) (53) (54) (55) (56) (57) (58) (59) mer Satisfaction and Dis-satisfaction (CS/ D) on Long-Haul Inclusive Tours A Reality Check on Theoretical Considerations’, Tourism Management, 22(1): 49–61. Botterill, D. T. (1987) ‘Dissatisfaction with a Construction of Satisfaction’, Annals of Tourism Research, 14(1): 139–40. Swan, J. E. and Trawick, I. F. (1981) ‘Satisfaction Explained by Desired vs Predictive Expectations’, in Bernhardt, K. L., Dolich, I., Etzel, M., Kehoe, W., Perreault, W. and Roering, K. (eds) The Changing Marketing Environment: New Theories and Applications, pp. 170–3. Chicago: American Marketing Association. Olshavsky, R. W. and Miller, J. A. (1972) ‘Consumer Expectations, Product Performance, and Perceived Product Quality’, Journal of Marketing Research, 9(February): 19–21. Whipple, T. W. and Thach, S. V. (1988) ‘Group Tour Management: Does Good Service Produce Satisfied Customers?’, Journal of Travel Research, 27(2): 16–21. Bowen, ref. 45 above. Geva and Goldman, ref. 15 above. Westbrook, R. A. and Newman, J. W. (1978) ‘An Analysis of Shopper Dissatisfaction for Major Household Appliances’, Journal of Marketing Research, 15(August): 456–66. Whipple and Thach, ref. 49 above. Woodruff et al., ref. 37 above. Weiermair, K. (2000) ‘Tourists’ Perceptions Towards and Satisfaction With Service Quality in the Cross-Cultural Service Encounter: Implications for Hospitality and Tourism Management’, Managing Service Quality, 10(6): 397–409. Zeithaml, V. A. (1988) ‘Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality and Value: A MeansEnd Model and Synthesis of Evidence’, Journal of Marketing, 2(2): 2–22. Carr, N. (2002) ‘The Tourism-Leisure Behavioural Continuum’, Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4): 972–86. Leontido, L. (1994) ‘Gender Dimensions of Tourism in Greece: Employment, SubStructuring and Restructuring’, in Kinnaird, V. and Hall, D. (eds) Tourism: A Gender Analysis, pp. 74–104. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. Valentine, G., Skelton, T. and Chambers, D. (1998) ‘Cool Places: An Introduction to Youth and Youth Cultures’, in Skelton, T. Bowie and Chang (60) (61) (62) (63) (64) (65) (66) (67) (68) (69) (70) (71) (72) (73) and Valentine, C. (eds) Cool Places: Geographies of Youth Cultures, pp. 132. London: Routledge. Oliver, R. L. and Swan, J. E. (1989) ‘Consumer Perceptions of Interpersonal Equity and Satisfaction in Transactions: A Field Survey Approach’, Journal of Marketing, 53(April): 21–35. Oliver, R. L. (1997) Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. Singapore: McGraw-Hill. Oliver, ref. 61 above. Francken, D. A. and Van Raaij, W. F. (1981) ‘Satisfaction with Leisure Time Activities’, Journal of Leisure Research, 13(4): 337–52. Oliver, R. L. and DeSarbo, W. S. (1988) ‘Response Determinants in Satisfaction Judgments’, Journal of Consumer Research, 14(March): 496–507. Webster, ref. 12 above. Hunt, H. K. (1977) ‘CS/D Overview and Future Research Directions’, in Hunt, H. K. (ed.) Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction, pp. 455–88. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. Westbrook, R. A. and Oliver, R. L. (1991) ‘The Dimensionality of Consumption Emotion Patterns and Consumer Satisfaction’, Journal of Consumer Research, 18(June): 84–91. Holbrook, M. B., Chestnut, R. W., Oliva, T. A. and Greenleaf, E. A. (1984) ‘Play as a Consumption Experience: The Roles of Emotions, Performance, and Personality in the Enjoyment of Games’, Journal of Consumer Research, 11(September): 728–39. Unger, L. S. and Kernan, J. B. (1983) ‘On the Meaning of Leisure: An Investigation of Some Determinants of the Subjective Experience’, Journal of Consumer Research, 9(March): 381–92. Holbrook, M. B. and Hirschman, E. C. (1982) ‘The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun’, Journal of Consumer Research, 9(September): 132–40. Holbrook et al., ref. 68 above. Bloch, P. H., Sherrell, D. L. and Ridgway, N. M. (1986) ‘Consumer Search: An Extended Framework’, Journal of Consumer Research, 13(June): 119–26. Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R. and Griffin, M. (1994) ‘Work and/or Fun: Measuring (74) (75) (76) (77) (78) (79) (80) (81) (82) (83) (84) (85) (86) (87) (88) (89) (90) Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value’, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(March): 644–56. Jorgensen, D. L. (1989) Participant Observation – A Methodology for Human Studies. London: Sage Publications. Gabbott and Hogg, ref. 24 above. Veal, A. J. (1997) Research Methods for Leisure and Tourism: A Practical Guide, 2nd edn. London: Pearson. Holloway, J. C. (1981) ‘The Guided Tour: A Sociological Approach’, Annals of Tourism Research, 8(3): 377–402; Arnould, E. E. and Price, L. L. (1993) ‘River Magic: Extraordinary Experience and the Extended Service Encounter’, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1): 24–45; Bowen, ref. 45 above; Seaton, A. V. (2002) ‘Observing Conducted Tours: The Ethnographic Context in Tourist Research’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 8(4): 309–19. Arnould and Price, ref. 77 above. Ryan, C. (1995) Researching Tourist Satisfaction – Issues, Concepts, Problems. London: Routledge. Seaton, A. V. (2000) ‘Another Weekend Away Looking for Dead Bodies: Battlefield Tourism on the Somme and in Flanders’, Journal of Tourism and Recreation Research, 25(3): 63–79. Seaton, ref. 80 above. Bowen, D. (2001) ‘Research on Tourist Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction: Overcoming the Limitations of a Positivist and Quantitative Approach’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(1): 31–40. Holloway, ref. 77 above. Rossman, G. B. and Rallis, S. F. (1998) Learning in the Field: An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications. Judd. C. M., Smith, E. R. and Kidder, L. H. (1991) Research Methods in Social Relations, 6th edn. London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Bowen, ref. 45 above. Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1997) Grounded Theory in Practice. London: Sage Publications. Spradley, J. P. (1980) Participant Observation. Orlando: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Wang, K. C., Hsieh, A. T. and Huan, T. C. (2000) ‘Critical Service Features in Group Package Tours: An Exploratory Research’, Tourism Management, 21(2): 177–89. Mancini, ref. 7 above. Page 321 Tourist satisfaction (91) Miller, ref. 32 above. (92) Crompton, J. L. (1979) ‘Motivations for Pleasure Vacation’, Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4): 408–24; Oppermann, M. and Chon, K. S. (1997) Tourism in Developing Countries. London: International Thomson Business Press; Swarbrooke and Horner, ref. 8 above. (93) Babin et al., ref. 73 above. (94) Pond, ref. 10 above. Page 322 (95) Lopez, ref. 15 above. (96) Reisinger, Y. and Turner, L. W. (2002) ‘Cultural Differences Between Asian Tourist Markets and Australian Hosts, Part 1’, Journal of Travel Research, 40(3): 295–315. (97) Barnlund, D. and Araki, S. (1985) ‘Intercultural Encounters: The Management of Compliments by Japanese and Americans’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 16(1): 9–26.