March Masterworks - Harrisburg Symphony Orchestra

advertisement

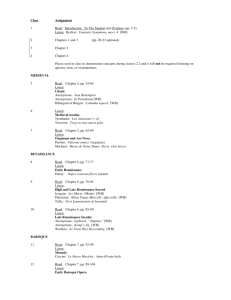

March 19-20, 2016 — page 1 About the Music by Dr. Richard E. Rodda Symphony No. 4, “Classique Sturm und Drang” (1995) — Nicolas Bacri Born November 23, 1961 in Paris The gifted and prolific French composer Nicolas Bacri, born in Paris in 1961, studied piano, theory and composition as a youngster and was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1979; he graduated in 1983 with a Premier Prix in composition. For the next two years, Bacri held a residency at the French Academy in Rome, where he came under the influence of the Italian modernist Giacinto Scelsi (1905–1988), who sought to join Eastern transcendent philosophy with Western sensibilities and musical resources in his meditative, hypnotic works. Bacri directed the chamber music department of Radio France after returning to Paris, but he left that position in 1991 to devote himself to composition. The large catalog of works he has created since — two operas, six symphonies, nearly thirty concertos, many compositions for chamber ensembles, piano, chorus and voice — have been performed widely throughout Europe, recorded often on major labels, and recognized with a Prix de Rome, Prix André Caplet de l’Académie des Beaux Arts, Prix Pierre Cardin de l’Académie des Beaux Arts, Grand Prix de la Nouvelle Académie du Disque and five awards from SACEM, the French association of authors, composers and publishers. Bacri has held residencies with the Casa de Velasquez in Madrid and with several French orchestras, and in 2013 made his debut as a conductor with the London Symphony Orchestra. From 1993 to 1998, Bacri was Composer-in-Residence with the Orchestre de Picardie in Amiens, a hundred miles north of Paris. The ensemble’s Music Director, Louis Langrée, dedicated several concerts during the 1995-1996 season to music of the late-18th-century German “Sturm und Drang” (“Storm and Stress”) movement, which created an emotionally charged style through the use of minor keys, sudden contrasts, chromatic harmonies and a pervasive sense of agitation, and he asked Bacri to write a new work appropriate to that theme. “I therefore gave myself over to the kind of attempt at updating that was beloved by a good number of Neo-Classical composers during the time between the world wars, and so wrote homages to Strauss, Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Weill. Listeners will also find many gestures that are personal to me as well as many that are inseparable from Prokofiev’s ‘Classical’ Symphony.” Bacri indicated that the opening Allegro fuocoso (“Fast, very fiery”) honors “the Richard Strauss of [the comic opera] Ariadne auf Naxos” in the jesting quality of many of its episodes, but its pungent harmonies and rhythmic dynamism are more indebted to Prokofiev. The Omaggio a Igor Stravinsky recalls the cool emotion, precise counterpoint and acerbic harmonies of that modern master’s Neo-Classical idiom. The gruff Menuetto pays tribute to Arnold Schoenberg, who fitted some of his earliest experiments in twelve-tone composition into old dance forms. The moto perpetuo finale, an homage, according to Bacri, to “the Kurt Weill of the muscular Second Symphony, not the Three-Penny Opera,” is capped by a furious fugue. March 19-20, 2016 — page 2 Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107 (1959) — Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906 in St. Petersburg Died August 9, 1975 in Moscow By the mid-1950s, Dmitri Shostakovich had developed a musical language of enormous subtlety, sophistication and range, able to encompass such pieces of “Socialist Realism” as the Second Piano Concerto, the Festive Overture, and the Symphonies No. 11 (“The Year 1905”) and No. 12 (“Lenin”), as well as the profound outpourings of the First Violin Concerto, the Tenth Symphony and the late string quartets. The First Cello Concerto, written for Mstislav Rostropovich during the summer of 1959, straddles both of Shostakovich’s expressive worlds, a quality exemplified by two anecdotes told by the great cellist himself: “Shostakovich gave me the manuscript of the First Cello Concerto on August 2, 1959. On August 6th I played it for him from memory, three times. After the first time he was so excited, and of course we drank a little bit of vodka. The second time I played it not so perfect, and afterwards we drank even more vodka. The third time I think I played the Saint-Saëns Concerto, but he still accompanied his Concerto. We were enormously happy....” “Shostakovich suffered for his whole country, for his persecuted colleagues, for the thousands of people who were hungry. After I played the Cello Concerto for him at his dacha in Leningrad, he accompanied me to the railway station to catch the overnight train to Moscow. In the big waiting room we found many people sleeping on the floor. I saw his face, and the great suffering in it brought tears to my eyes. I cried, not from seeing the poor people but from what I saw in the face of Shostakovich....” The ability of Shostakovich’s music, like the man himself, to display the widest possible range of moods in succession or even simultaneously is one of his most masterful achievements. (The same may be said of Mahler, whose music was an enormous influence on Shostakovich.) The opening movement of the First Cello Concerto may be heard as almost Classical in the clarity of its form and the conservatism of its harmony and themes, yet there is a sinister undercurrent coursing through this music, a bleakness of spirit not entirely masked by the ceaseless activity. The following Moderato grows from sad melodies of folkish character, piquantly harmonized, which are gathered into a huge welling up of emotion before subsiding to close the movement. The extended solo cadenza that follows without pause is an entire movement in itself. (Shostakovich had used a similar formal technique in the Violin Concerto No. 1 of 1948.) Thematically, it springs from the preceding slow movement, and reaches an almost Bachian depth of feeling. The cadenza leads directly to the finale, one of Shostakovich’s most witty and sardonic musical essays. With disarming ease, the main theme of the first movement is recalled in the closing section of the finale to round out the Concerto’s form. “It is difficult to think of any modern concerto,” wrote Alan Frank, “which pursues its objectives in so purposeful a manner with little or no exploration of by-ways.” March 19-20, 2016 — page 3 In addition to its purely musical value, Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto deserves a significant footnote in Russia’s modern artistic history. The piece was written for Rostropovich, about whom the composer said in his purported memoirs, Testimony, “In general, Rostropovich is a real Russian; he knows everything and he can do everything. I’m not even talking about music here, I mean that Rostropovich can do almost any manual or physical work, and he understands technology.” Shostakovich and Rostropovich were close friends during the composer’s later years, and they lived as neighbors for some time in the Composers’ House in Moscow. Rostropovich gave the Concerto both its world premiere (Leningrad; October 4, 1959) and its first American performance (Philadelphia; November 6, 1959), and was the inspiration for Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 2 of 1966. In 1974, Rostropovich and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, defected to live and work in the West; four years later they were deprived of their Russian citizenship and became “non-persons” in their native land. In 1979 Dmitri and Ludmilla Sollertinsky published their Pages from the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich, which was essentially the Soviet rebuttal to the scathing criticism leveled in Testimony, issued several months earlier. Though Rostropovich was one of Shostakovich’s best friends and most important artistic motivators, his name is not even mentioned in the Sollertinskys’ Pages, and the fine First Cello Concerto is dismissed in the book with a mere, passing half-sentence. Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36 (1802) — Ludwig van Beethoven Born December 16, 1770 in Bonn Died March 26, 1827 in Vienna In the summer of 1802, Beethoven’s physician ordered him to leave Vienna and take rooms in Heiligenstadt, today a friendly suburb at the northern terminus of the city’s subway system, but two centuries ago a quiet village with a view of the Danube across the river’s rich flood plain. It was three years earlier, in 1799, that Beethoven first noticed a disturbing ringing and buzzing in his ears, and he sought medical attention for the problem soon after. He tried numerous cures for his malady, as well as for his chronic colic, including oil of almonds, hot and cold baths, soaking in the Danube, pills and herbs. For a short time, he even considered the modish treatment of electric shock. On the advice of his latest doctor, Beethoven left the noisy city for the quiet countryside with the assurance that the lack of stimulation would be beneficial to his hearing and his general health. In Heiligenstadt, Beethoven virtually lived the life of a hermit, seeing only his doctor and a young student named Ferdinand Ries. In 1802, Beethoven was still a full decade from being totally deaf. The acuity of his hearing varied from day to day (sometimes governed by his interest — or lack thereof — in the surrounding conversation), but he had largely lost his ability to hear soft sounds by that time, and loud noises caused him pain. Of one of their walks in the country, Ries reported, “I called his attention to a shepherd who was piping very agreeably in the woods on a flute made of a twig of elder. For half an hour, Beethoven could hear nothing, and though I assured him that it was the same with me (which was not the case), he became extremely quiet and morose. When he occasionally seemed to be merry, March 19-20, 2016 — page 4 it was generally to the extreme of boisterousness; but this happens seldom.” In addition to the distress over his health, Beethoven was also wounded in 1802 by the wreck of an affair of the heart. He had proposed marriage to Giulietta Guicciardi (the thought of Beethoven as a husband threatens the moorings of one’s presence of mind!), but had been denied permission by the girl’s father for the then perfectly valid reason that the young composer was without rank, position or fortune. Faced with the extinction of a musician’s most precious faculty, fighting a constant digestive distress, and unsuccessful in love, it is little wonder that Beethoven was sorely vexed. On October 6, 1802, following several months of wrestling with his misfortunes, Beethoven penned the most famous letter ever written by a musician — the “Heiligenstadt Testament.” Intended as a will written to his brothers (it was never sent, though he kept it in his papers to be found after his death), it is a cry of despair over his fate, perhaps a necessary and self-induced soul-cleansing in those pre-Freudian days. “O Providence — grant me at last but one day of pure joy — it is so long since real joy echoed in my heart,” he lamented. But — and this is the miracle — he not only poured his energy into self-pity, he also channeled it into music. “I shall grapple with fate; it shall never pull me down,” he resolved. The next five years were the most productive he ever knew. The Second Symphony of 1802 opens with a long introduction moving with a stately tread. The sonata form begins with the arrival of the fast tempo and the appearance of the main theme, a brisk melody first entrusted to the low strings. Characteristic Beethovenian energy dominates the transition to the second theme, a martial strain paraded by the winds. The development includes two large sections, one devoted to the main theme and its quick, flashing rhythmic figure, the other exploring the possibilities of the marching theme. The recapitulation compresses the earlier material to allow a lengthy coda to conclude the movement. Professor Donald Tovey thought the Larghetto to be “one of the most luxurious slow movements in the world”; Sir George Grove commented on its “elegant, indolent beauty.” So lyrical is its principal theme that, by appending some appropriate words, Isaac Watts converted it into the hymn Kingdoms and Thrones to God Belong. The movement is in a full sonata form, with the first violins giving out the second theme above a rocking accompaniment in the bass. Beethoven labeled the third movement “Scherzo,” the first appearance of that term in his symphonies, though the comparable movement of the First Symphony was a true scherzo in all but name. Faster in tempo and more boisterous in spirit than the minuet traditionally found in earlier symphonies, the scherzo became an integral part not only of Beethoven’s later works, but also of those of most 19th-century composers. A rising three-note fragment runs through much of the scherzo proper, while the central trio gives prominence to the oboes and a delightful walking-bass counterpoint in the bassoons. The finale continues the bubbling high spirits of the scherzo. Formally a hybrid of sonata and rondo, it possesses a wit and structure indebted to Haydn, but a dynamism that is Beethoven’s alone. The long coda intensifies the bursting exuberance of the music, and carries it along to the closing pages of the movement. ©2015 Dr. Richard E. Rodda HARRISBURG SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Saturday, March 19, 2016 at 8:00 p.m. Sunday, March 20, 2016 at 3:00 p.m. STUART MALINA, Conducting ZUILL BAILEY, Cello Symphony No. 4, “Classique Sturm und Drang” Allegro fuocoso: Omaggio a Richard Strauss Arietta: Omaggio a Igor Stravinsky Menuetto: Omaggio a Arnold Schoenberg Finale: Omaggio a Kurt Weill Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107 Allegretto Moderato — Cadenza — Allegro con moto Nicolas Bacri (b. 1961) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) — INTERMISSION— Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36 Adagio molto — Allegro con brio Larghetto Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)