Rounds

advertisement

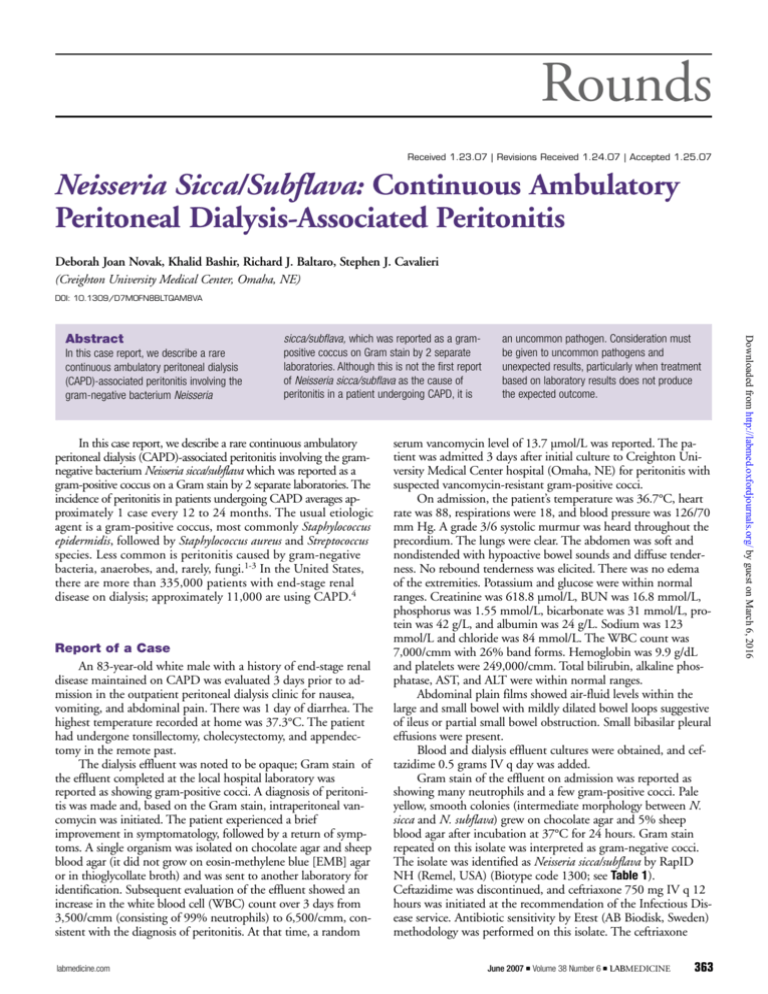

Rounds Received 1.23.07 | Revisions Received 1.24.07 | Accepted 1.25.07 Neisseria Sicca/Subflava: Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis-Associated Peritonitis Deborah Joan Novak, Khalid Bashir, Richard J. Baltaro, Stephen J. Cavalieri (Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE) DOI: 10.1309/D7M0FN8BLTQAM8VA In this case report, we describe a rare continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)-associated peritonitis involving the gram-negative bacterium Neisseria sicca/subflava, which was reported as a grampositive coccus on Gram stain by 2 separate laboratories. Although this is not the first report of Neisseria sicca/subflava as the cause of peritonitis in a patient undergoing CAPD, it is In this case report, we describe a rare continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)-associated peritonitis involving the gramnegative bacterium Neisseria sicca/subflava which was reported as a gram-positive coccus on a Gram stain by 2 separate laboratories. The incidence of peritonitis in patients undergoing CAPD averages approximately 1 case every 12 to 24 months. The usual etiologic agent is a gram-positive coccus, most commonly Staphylococcus epidermidis, followed by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species. Less common is peritonitis caused by gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, and, rarely, fungi.1-3 In the United States, there are more than 335,000 patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis; approximately 11,000 are using CAPD.4 Report of a Case An 83-year-old white male with a history of end-stage renal disease maintained on CAPD was evaluated 3 days prior to admission in the outpatient peritoneal dialysis clinic for nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. There was 1 day of diarrhea. The highest temperature recorded at home was 37.3°C. The patient had undergone tonsillectomy, cholecystectomy, and appendectomy in the remote past. The dialysis effluent was noted to be opaque; Gram stain of the effluent completed at the local hospital laboratory was reported as showing gram-positive cocci. A diagnosis of peritonitis was made and, based on the Gram stain, intraperitoneal vancomycin was initiated. The patient experienced a brief improvement in symptomatology, followed by a return of symptoms. A single organism was isolated on chocolate agar and sheep blood agar (it did not grow on eosin-methylene blue [EMB] agar or in thioglycollate broth) and was sent to another laboratory for identification. Subsequent evaluation of the effluent showed an increase in the white blood cell (WBC) count over 3 days from 3,500/cmm (consisting of 99% neutrophils) to 6,500/cmm, consistent with the diagnosis of peritonitis. At that time, a random labmedicine.com an uncommon pathogen. Consideration must be given to uncommon pathogens and unexpected results, particularly when treatment based on laboratory results does not produce the expected outcome. serum vancomycin level of 13.7 µmol/L was reported. The patient was admitted 3 days after initial culture to Creighton University Medical Center hospital (Omaha, NE) for peritonitis with suspected vancomycin-resistant gram-positive cocci. On admission, the patient’s temperature was 36.7°C, heart rate was 88, respirations were 18, and blood pressure was 126/70 mm Hg. A grade 3/6 systolic murmur was heard throughout the precordium. The lungs were clear. The abdomen was soft and nondistended with hypoactive bowel sounds and diffuse tenderness. No rebound tenderness was elicited. There was no edema of the extremities. Potassium and glucose were within normal ranges. Creatinine was 618.8 µmol/L, BUN was 16.8 mmol/L, phosphorus was 1.55 mmol/L, bicarbonate was 31 mmol/L, protein was 42 g/L, and albumin was 24 g/L. Sodium was 123 mmol/L and chloride was 84 mmol/L. The WBC count was 7,000/cmm with 26% band forms. Hemoglobin was 9.9 g/dL and platelets were 249,000/cmm. Total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, AST, and ALT were within normal ranges. Abdominal plain films showed air-fluid levels within the large and small bowel with mildly dilated bowel loops suggestive of ileus or partial small bowel obstruction. Small bibasilar pleural effusions were present. Blood and dialysis effluent cultures were obtained, and ceftazidime 0.5 grams IV q day was added. Gram stain of the effluent on admission was reported as showing many neutrophils and a few gram-positive cocci. Pale yellow, smooth colonies (intermediate morphology between N. sicca and N. subflava) grew on chocolate agar and 5% sheep blood agar after incubation at 37°C for 24 hours. Gram stain repeated on this isolate was interpreted as gram-negative cocci. The isolate was identified as Neisseria sicca/subflava by RapID NH (Remel, USA) (Biotype code 1300; see Table 1). Ceftazidime was discontinued, and ceftriaxone 750 mg IV q 12 hours was initiated at the recommendation of the Infectious Disease service. Antibiotic sensitivity by Etest (AB Biodisk, Sweden) methodology was performed on this isolate. The ceftriaxone June 2007 䊏 Volume 38 Number 6 䊏 LABMEDICINE 363 Downloaded from http://labmed.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 Abstract Rounds Table 1_RapID NH Biochemical Reactions for Neisseria Sicca/Subflava Test Reaction Proline p-nitroanilide (PRO) γ-Glutamyl p-nitroanilide (GGT) o-Nitrophenyl, β,D-galactoside (ONPG) Glucose (GLU) Sucrose (SUC) Fatty acid ester (EST) Resazurin (RES) p-Nitrophenyl phosphate (PO4) Ornithine (ORN) Urea (URE) Nitrate (NO3) Tryptophane (IND) Positive Negative Negative Positive Positive Negative Negative Negative Negative Negative Negative Negative 1. Saklayen MG. CAPD peritonitis. Incidence, pathogens, diagnosis, and management. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:997–1009. 2. Port FK. Risk of peritonitis and technique failure by CAPD connection technique. A national study. Kidney Int. 1992;42:967–974. 3. Holley JL, Bernardini J, Piraino B. Infecting organisms in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients on the Y-set. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994; 23:569–573. Discussion Neisseria sicca is a gram-negative diplococcus found as normal human oral and upper respiratory tract flora; it is considered one of the commensal Neisseria species. It has the ability to degrade hydrogen peroxide, living as a commensal in the oropharynx with hydrogen peroxide-producing and hydrogen peroxide-degrading oral flora in salivary sediment and dental plaques.6 Neisseria sicca produces acid from glucose, maltose, fructose, and sucrose. It does not utilize lactose. Neisseria subflava produces acid from glucose, maltose, and variably from fructose and sucrose. Both are oxidase positive and produce H2S from lead acetate. Neisseria sicca strains are biochemically indistinguishable from Neisseria subflava biovar perflava. They can be distinguished by subtle differences in colony color and texture;7,8 hence, the organism is sometimes termed Neisseria sicca/subflava. Fatty chain analysis and sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene may also be used in identification. The commensal Neisseria species are known to occasionally cause invasive disease in humans, more likely in immunocompromised patients. Case reports of serious infections caused by the commensal Neisseria species have included bacteremia, endocarditis, meningitis, and septic arthritis. Three cases of N. sicca/subflava peritonitis have been reported in Europe in 364 LABMEDICINE 䊏 Volume 38 Number 6 䊏 June 2007 4. United States Renal Data System Annual Data Report 2006. Part D: Treatment Modality. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestion and Kidney Disease. National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health and Human Services. 5. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Sixteenth Informational Supplement. 2006:26:60–61,132–133. 6. Ryan CS, Kleinberg I. Bacteria in human mouths involved in the production and utilization of hydrogen peroxide. Arch Oral Biol. 1995;40:753–763. 7. Janda W. In: Murray PR, ed. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 8th ed. ASM Press; 2003:602–603. 8. Murphy TF. In: Mandel GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th ed. Churchhill Livingstone; 2004:2532. 9. Vermeij CG, van Dam DW, Oosterkamp HM, et al. Neisseria subflava biovar perflava peritonitis in a continuous cyclic peritoneal dialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1608. 10. Papaefstathiou C, Zoumberi M, Arvanitis D, et al. Neisseria sicca peritonitis in a patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A case of the “nonpathogenic” Neisseriae infection. Abstract. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:453. 11. Konner P, Watschinger B, Apfalter P, et al. A case of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis peritonitis with an uncommon organism and an atypical course. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:E10. 12. Neu AM, Case B, Lederman HM, et al. Neisseria sicca peritonitis in a patient maintained on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1994;8:601–602. 13. Shooter JR, Howles MJ, Baselski VS. Neisserial infections in dialysis patients. Clin Micro Newls. 1990;12:15–16. labmedicine.com Downloaded from http://labmed.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 minimum inhibitory concentration was 0.094 µg/mL. The interpretive breakpoint for N. gonorrheae against ceftriaxone is <0.25 µg/ml (susceptible). No minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) interpretive standards exist for N. sicca/subflava (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute).5 Blood cultures were negative. By day 3 of ceftriaxone, the patient reported decreased abdominal pain, and by day 4 the patient was able to tolerate removal of the nasogastric tube. By day 7, the patient was clinically asymptomatic, with negative culture of the effluent. Cell count on the effluent completed on day 7 showed 810 WBC/mm3 with 59% neutrophils and 39% mononuclear cells. Cell count on the effluent completed 10 days after admission consisted of 29 WBC/mm3 with 6% neutrophils and 92% mononuclear cells. The patient was discharged on ceftriaxone 750 mg IV q 12 hours to a skilled care facility. patients on CAPD.9-11 In the United States, cases in a pediatric patient and an adult, both on chronic peritoneal dialysis, have been reported.12,13 There appears to be significance in the fact that, in this case, 2 separate hospital-based microbiology laboratories initially identified the organism as a gram-positive coccus on a Gram stain of the original specimen. In the first laboratory, the isolate was sent out for identification, producing a delay in diagnosis and the initiation of appropriate antibiotic coverage. It is not uncommon for Gram stains to exhibit uneven staining, thus it is possible for a technologist to choose to read a variablystaining Gram stain of cocci as gram positive, particularly if gram-positive cocci are suspected. However, Acinetobacter species have been noted to resist decolorization, and this phenomenon has been reported for Neisseria species as well.13 In this case, the error resulted in a delay in initiation of appropriate treatment. In this patient, it is likely that the organism originated from the patient’s oropharynx. After the patient’s return home, a nurse visited to review the patient’s aseptic technique and home circumstances. Potential problems were identified in hand washing technique and lack of face mask use. Although this is not the first report of Neisseria sicca/subflava as the cause of peritonitis in an adult patient in the United States undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, it is an uncommon pathogen. Consideration must be given to uncommon pathogens and unexpected results, particularly when treatment based on laboratory results does not produce the expected outcome. LM