Comparison of the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis

advertisement

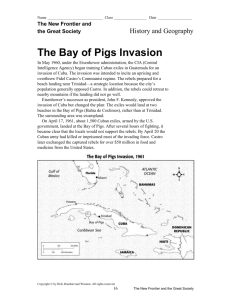

Mandie L. Webb Student Number 1037937 IS 305 KA Professor December 1, 2004 Comparison of the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis ABSTRACT −1− This paper looks at the historical aspects of the Bay of Pigs Operation and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Through comparison of these two Cold War milestones it is evident that fundamental changes in the interaction between intelligence and policy occurred in the eighteen month period between the spring of 1961 and fall of 1962. This paper examines the historical aspects by reviewing the great disparities between poor planning and oversight, unrealistic success estimates, miscommunication, narrow intelligence forecasts, and media awareness during the Bay of Pigs Operation versus the Cuban Missile Crisis. Failures during the Cuban Plan (Bay of Pigs Operation) are pin pointed and analyzed in terms of their contribution to the successes of the Cuban Missile Crisis. These contributors had a tremendous impact on the growth of President Kennedy’s Administration and the CIA, during the Cuba Missile Crisis. This paper surmises that the humiliation surrounding the failure of the Bay of Pigs Operation caused the Kennedy Administration to effectively change the relationship between intelligence and policy making. Introduction −2− Failure during the invasion of the Bay of Pigs significantly affected the relationship between policy and intelligence under President Kennedy’s Administration. The ripple effect was evident in Kennedy’s planning and policy decisions relating to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Failure at the Bay of Pigs was devastating for the newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy. Within just a few months of being voted into office, the President, found himself involved in an underhanded conspiracy to overthrow the government of Cuban Dictator Fidel Castro. The Bay of Pigs incident caused the democratic juggernaut to stumble as the world=s opinions were being pulled in opposite directions. The covert acts of the Central Intelligence Agency and the sanctioning of such acts by American political leaders shamefully placed the American ethic in a quandary. President Kennedy would never be placed in this position again; from the Bay of Pigs forward, the President never again looked at intelligence or the advice of intelligence agencies as he had in the first days of his administration. The Bay of Pigs fiasco determined two things for sure: one, policy would not be decided based solely on the intelligence given to the President and two, policy would be true to the mettle of America’s leadership and her people (Kennedy, 1971). 1 Brief Synopsis of the Bay of Pigs The volatility of Cuba’s revolution in the 1950's cumulated in the overthrow of the Batista regime by Fidel Castro. Initially, Castro’s regime was recognized as an improvement over the former Cuban leader, but fifteen months after Castro came to power the United States 1 Kennedy, Robert F. (1971).Thirteen days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton &Company, Inc. −3− pulled their support for his regime. Castro’s Communist Government and close relationship with the Soviet Union alarmed American leadership; Cuba was the first Communist country in the western hemisphere to convert to Communism. The United States feared that tolerance of the Cuban Communism would enable Soviet influence to spread to other vulnerable nations within the hemisphere. Furthermore, a failure to limit Communism within the hemisphere would undermine America’s ability to Aprevent the spread of Soviet influence over smaller nations, especially within America’s western hemisphere. (Persons, 1990, p. ix) 2 The American government (more precisely the Central Intelligence Agency) under President Eisenhower constructed a plan (as early as March of 1960) to carry out the removal of Fidel Castro. 3 The plan entailed four distinct phases: the organization of a political entity, the recruitment of soldiers, a propaganda campaign, and the assassination of Fidel Castro.(English, 1984) 4 The first piece the Central Intelligence Agency had to piece together was a political organization that could garner support for the revolution. This body had to be capable of acting as a legitimate political agency and gathering a militia to conduct the revolutionary Cuban Plan. The CIA chose initially to support a Cuban political organization called the Frente Revolucioniaro Democratico. This council Aproved useful as a cover and administrative mechanism... (CIA, 1961) 5 , but was limited in scope due to its inability to gather required 2 Persons, Albert C. (1990). The Bay of Pigs. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. 3 English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm 4 English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm 5 US Central Intelligence Agency. (March 1961). Proposed Operation Against Cuba.. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.paperlessarchives.com/baypigs.html −4− militiamen. Realizing this inability, the Central Intelligence Agency wisely reorganized the group; making the Frente Revolucioniaro Democratico a small portion of a larger body. This new structure proved more suitable for yielding the men needed to lead, recruit, and conduct the revolution. The second and third pieces of the plan were designed to encourage civilian communities to join the revolution. The second piece of the plan was the recruitment, training, equipping, and delivery of soldiers. Fifteen Hundred men were responsible for invading Cuba, fueling unrest among civilian communities, and transforming this civilian unrest into to a revolution. The third piece consisted of a vigorous propaganda campaign. Extensive radio broadcasts were aired over Cuban broad band in the effort to reach rural Cuban Communities. The final piece of the tapestry was the assassination of Fidel Castro. (English, 1984) 6 The assassination plot was not disclosed to the G-2 think tank planners of the Cuban Plan. In fact only Central Intelligence Officials, such as Deputy Director for Plans Richard Bissell, acknowledged prior knowledge of the assassination plot and factored it into planning assessments. (Warner, 1999) 7 If the assassination had been successful, the other three stages of the plan would be unnecessary. By early January of 1961, the Central Intelligence agency had in place the four components of the Cuban Plan and was ready to conduct the covert Cuba Plan. The operation, 6 English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm 7 Warner, Michael. (1999). The CIA=s Internal Probe of the Bay of Pigs Affair. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.cia.gov/search?NS-search-page=document&NS-rel-doc-name=/csi/studies/winter98_99/art08.html&NSquery=bay+of+pigs&NS-search-type=NS-boolean-query&NS-collection=Entire%20Site&NS-docs-found=47&NS-d oc-number=1 −5− dubbed JMATE (CIA, 1961) 8 , was a complex plan designed to externally stimulate a Cuban revolution in favor of US interests. April 15, 1961, was selected as the provisionary “go” date for the Bay of Pigs Operation. This decision was based on the widely held belief that this particular time period was the opportune time to gain maximum anti-Castro support without committing American military forces, and before Castro’s weapons and technicians, provided by the Soviets, arrived in Cuba. (Warner, 1999 and English, 1984) 9 The US Government’s ACuban Plan@ launched on April 15, 1961, with the deployment of 160 man reconnaissance team. This reconnaissance team’s landing was designed to create a diversion, which would draw Castro’s forces eastward, away from the actual invasion forces. The diversionary landing was abandoned by the reconnaissance team, because they believed the landing had been compromised. The early morning hours of April 15, 1961, brought bombing strikes against Castor’s military forces; key targets of the strikes were Castro’s air defenses, because destruction of the Cuban Air Force would decisively weaken Castro’s military forces. Unfortunately, strikes were only able to definitively destroy five aircraft and damage an undefined number of others, which reduced the effect air strikes had on abilities of Cuban ground forces. Mid afternoon on April 15, 1961, President Kennedy gave the green light to proceed with the invasion; however, just prior to the landing of the initial assault forces on the 8 US Central Intelligence Agency. (March 1961). Proposed Operation Against Cuba.. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.paperlessarchives.com/baypigs.html 9 English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm Warner, Michael. (1999). The CIA=s Internal Probe of the Bay of Pigs Affair. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.cia.gov/search?NS-search-page=document&NS-rel-doc-name=/csi/studies/winter98_99/art08.html&NSquery=bay+of+pigs&NS-search-type=NS-boolean-query&NS-collection=Entire%20Site&NS-docs-found=47&NS-d oc −6− evening of April 16, 1961, the Kennedy Administration sent a cable canceling the air strikes that were to support the landing forces. CIA officials attempted to alter the administrations decision, but were unsuccessful. The CIA notified in-route invasion forces of the cancellation, but reiterated the “green light” on the invasion. Unfortunately, invasion forces met with significant resistance as they made their landings along the Bay of Pigs. Castro’s forces were in place prior to the landings; a result of Castro’s monitoring of American press sources. Complications during the landing of invasion forces, the cancellation of air strikes, and ultimately the inability of the invasion forces to hold the beachhead, all combined to spell the defeat and capture of invasion forces, and the failure of America’s covert plan to topple the Castro’s regime. Brief Overview of the Cuban Missile Crisis The humiliating failure of the Bay of Pigs Operation contributed greatly to changes in the Kennedy Administration’s decision making process and the ultimate policy outcome of another Cold War milestone: The Cuban Missile Crisis. Once again, the Kennedy Administration found itself embroiled in a dispute over the island of Cuba. In September 1962, the administration was provided with conclusive photographic evidence of Soviet nuclear missile weapon systems in Cuba. This photographic evidence forced the administration to confront the prospect of the introduction of long range nuclear missiles staged within ninety miles of the America’s Southern Coast. On Tuesday, October 16, 1962, U-2 spy plane photos were brought to the attention of President Kennedy and his administration. The photos were of terrain in Cuba where there appeared to be a build up of Soviet long range nuclear missiles. This revelation rocked the −7− administration, because of the seriousness of the finding. Within thirteen short days, President Kennedy, with the aid of close advisors, friends, and family, confirmed the existence of nuclear missiles on Cuban soil, settled on a course of action, and resolved the issue without aggressive action. Comparison of the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis Lessons learned in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs affair significantly changed President Kennedy’s use of intelligence information in policy decision making during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Several key failures, both on the part of the President and the Central Intelligence Agency, were uncovered in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs. Exploration of these failures directly lend to the changes within the Kennedy Administration following the fiasco. Clearly, for most Americans, a significant portion of the failure was attributed to President Kennedy’s decision to cancel the air strikes planned for D-day. However true this estimate is, the President cannot shoulder the blame alone. The Central Intelligence Agency’s planning process placed a great deal of emphasis on the use of air strikes in support of invasions forces, but CIA officials failed, early on, to impress upon the administration the necessity of the support air strikes. The agency chose, rather to accept the administrations decision, and failed to notify the President of the likelihood that his decision would greatly reduce the success rate of the Cuban Operation. (Warner, 1999) 10 Without knowledge of the air strikes necessity, President Kennedy chose to abandon the air strikes under pressure from the United Nations and a need to 10 Warner, Michael. (1999). The CIA=s Internal Probe of the Bay of Pigs Affair. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.cia.gov/search?NS-search-page=document&NS-rel-doc-name=/csi/studies/winter98_99/art08.html&NSquery=bay+of+pigs&NS-search-type=NS-boolean-query&NS-collection=Entire%20Site&NS-docs-found=47&NS −8− savior A... final shreds of denial of complicity in the operation... (English, 1984) 11 Cancellation of the D-day air strikes, undoubtedly, increased the risk of failure, but the cancellation was not the only error made by the US officials. Failure for the operation overwhelmingly rests with the CIA and these failures were plentiful. Among Central Intelligence miscalculations were: poor planning and oversight, unrealistic success estimates, miscommunication, narrow intelligence forecasts, and media awareness. The secrecy of the Bay of Pigs operation was paramount due to the illegalities of the operation and the operation’s need for the element of surprise. The depths of secrecy backfired on the CIA leading to several key problems. First, the agency distributed information on a need to know basis only; this created problems with checks and balances as the operation’s planning materialized. Branch Four of the CIA created a new think tank (G-2) to plan the execution of Bay of Pigs invasion. G-2 was independent of Branch Four’s Foreign Intelligence Section, a section that could have provided oversight to the group as the operation plan was created. Since only G-2 was privy to planning information the Foreign Intelligence Section was unable to aid their counterpart in judgment decisions. Had the agency shared vital information with the operation’s planners and provided oversight for the planning element, G-2 could have more closely estimated the likelihood of a successful outcome. Furthermore, stumbling points of the G-2 plan could have been ironed out with outside assistance from Branch Four’s Foreign Intelligence Section. This would have lead to a more comprehensive plan and possibly a better outcome. 11 English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm −9− Secrecy also contributed to the false sense of success CIA officials, with greater knowledge of the Bay of Pigs operation, had for the outcome of the operation. For instance, Deputy Director for Plans Richard Bissell factored the assassination plot into his estimates of the success of the operation; however, G-2 planners were unaware of the Castro assassination plot. (Warner, 1999) 12 These positive estimates were shared with policy makers, which in turn created a false sense of optimism among policy makers in Washington. Optimistic operation’s briefings masked the high potential for failure of the Bay of Pigs operation. By briefing Washington Officials with more realistic success estimates, policy makes would have been in a better position to judge whether the operation should have gone forward or not. Here it becomes evident the agency made errors planning the Bay of Pigs Operation, but what is more significant is the lack of planning for the steps after the operations initial stage. According to Piero Gleijeses, the real failure of the agency was in the lack of planning for the probable inability of the invasion forces to hold their emplacements. This lack of planning stems from two causes: first, the CIA felt that planning events after initial stages was not sensible due to the great variety of outcomes that could present themselves after the landing of forces and second, CIA intelligence estimates reckoned that Castro’s military would be to weak to repel the invasion and that the President would send in American forces if the invasion appeared to waffle. However correct the agency was about the difficulty of planning operational stages, this does not excuse the apparent communications breakdown over the use of US military forces to save the 12 Warner, Michael. (1999). the CIA=s Internal Probe of the Bay of Pigs Affair. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.cia.gov/search?NS-search-page=document&NS-rel-doc-name=/csi/studies/winter98_99/art08.html&NSquery=bay+of+pigs&NS-search-type=NS-boolean-query&NS-collection=Entire%20Site&NS-docs-found=47&NS-d oc-number=1 −10− effort, if, invasion forces were in peril. At no time did the President or his administration give the agency any reason to believe that US forces would be deployed to save the revolutionary movement. In fact, the administration went to get lengths to ensure that American involvement in the Cuban plan was not evident. Although this was Washington’s attitude, CIA officials (including DCI Dulles) believed the President would comment US troops to the movement if needed and approved plans based on this theory. (Warner, 1999) 13 Miscommunications, unrealistic success estimates, and poor planning and oversight on the part of the CIA were the basis for substantive changes within the Kennedy Administration as they related to the use of intelligence in policy deliberations. During the Bay of Pigs Era, the administration received CIA intelligence and reporting unfiltered and directly for the horses mouth. The president conferred secretly with the CIA and accepted at face value the information being reported. However during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, President Kennedy decidedly chose to take another more cautious route. Certainly, the very seriousness of the Cuban Missile situation prompted caution, but according to Robert Kennedy, the President had learned a valuable lesson: AHaving depended on the national security apparatus alone in making the fatal choice about the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy insisted thereafter that no major national security decision be made without including RFK (Robert Kennedy) and Sorensen in the process. (R. Kennedy, 1971, 13 Warner, Michael. (1999). The CIA=s Internal Probe of the Bay of Pigs Affair. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.cia.gov/search?NS-search-page=document&NS-rel-doc-name=/csi/studies/winter98_99/art08.html&NSquery=bay+of+pigs&NS-search-type=NS-boolean-query&NS-collection=Entire%20Site&NS-docs-found=47&NS-d oc-number=1 −11− p. 114) 14 Kennedy chose to utilize a council of officials, experts, and close friends to mull over the photographic intelligence provided by U-2 flights over Cuba. This council was also used to formulate and critique possible courses of action. Through this council the President was able to confidentially choose the blockade approach to resolve the missile crisis instead of a more aggressive military stance. A second area lacking in the CIA’s planning preparations were the forms of intelligence used, gathered, and exploited during the Bay of Pigs. In gathering intelligence for the Bay of Pigs Operation the CIA relied heavily on statements of Cuban exiles. The lack of access to high level military officials within the Cuban Government caused the agency to center their intelligence efforts on Cuban exiles in Florida; the information gathered from exiles was fragmentary and biased. The information gathered was unable to provide the agency with a complete picture of the political situation in Cuba. For example, the CIA received information stating that some thirty-two tactical commanders in the Cuban military would defect if an invasion occurred, but promises of this nature never materialized. (Pentagon, 1961) 15 Unfortunately, the agency factored this assumption into the Bay of Pigs planning estimates, but failed to consider news and traveler accounts dispelling rumors of poverty and discontent... (English, 1984) 16 Furthermore, these 14 Kennedy, Robert F. (1971).Thirteen days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton &Company, Inc. 15 Pentagon: Ninth Meeting. (May 1961). Memorandum for Record: Paramilitary Study Group Meeting. Retrieved on November 14, 2004 from http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB29/03-01.htm 16 English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm −12− same reports claimed Castro’s popularity was on the rise. Unfortunately for the CIA, human intelligence was the single largest intelligence contributor during the planning stages of the Bay of Pigs Operation. There was some limited photographic evidence pertaining to Castor’s military strengths and weaknesses, but this provided only information important to the time table of the operation and not pertinent to the operations conduct. During the Cuban Missile Crisis the CIA and intelligence community learned that photographic and signals intelligence provided more concrete intelligence information when compared to human intelligence. Human intelligence can be subjective and incorrect, as was the case in the Cuban Plan. Concrete intelligence, like photographs and signals intelligence (like that used in the Cuban Missile Crisis) is believable and less circumstantial. The latter point was extremely important in dealing with the Cuban Missile Crisis, because the photographic evidence proved to the American people and the world that nuclear missiles were present in Cuba. Lastly, the Central Intelligence Agency and the Kennedy Administration failed to involve the media during the Bay of Pigs Operation. The media is always an important consideration during any political decision making process. During the Bay of Pigs Operation, the media was not considered or informed on any level; hence the media ran stories predicting an invasion of Cuba. The invasion reports ran by US media sources tipped off Castro, who wisely monitored American news sources. Having knowledge of the invasion, Castro developed a plan to head off invasion forces. This failure allowed the media to make assumptions, assumptions that allowed −13− Castro to gain knowledge of the invasion, which denied the invaders the crucial element of surprise. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, however, the Kennedy Administration cleverly went directly to the media once a plan of action had been reached. This allowed the administration to publicly announce the crisis first, and thus the administration was able to manipulate the media, in a manor of speaking. Had the administration chose to take covert action against the Soviets, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the media would have inevitably found out and been very critically of the administration’s decision. But, since the administration was forthcoming with the dire situation, the media was receptive and supportive of the administration’s blockade decision. The media effectively aided the President in garnering American and worldwide support for the blockade of Soviet ships, an action that ultimately led to the resolution of the crisis. The Aftermath The Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis were both milestones of the Cold War faced by President Kennedy and his administration. The two incidents differed greatly in their context, severity, and their outcomes. More importantly, the two incidents impacted the relationship between policy and intelligence during the Kennedy Administration. The Bay of Pigs was an operation designed to over throw Fidel Castor, and spurn the growth of communism in the western hemisphere. Unfortunately, months of covert planning and training by the Central Intelligence Agency unraveled as Castro’s military forces crushed the bay of Pigs Invasion Force. The CIA’s humility was compound in the aftermath of the incident by the uncovering of planning and operational errors. Errors in planning and oversight, success estimates, communication, intelligence forecasts, and media handling directly hampered the −14− otherwise precarious operation. Uncovering of the Central Intelligence Agency’s errors caused the Kennedy Administration to become cautious of the intelligence received in the Bay of Pigs aftermath. The administration was sensitive to the criticism it received and strove to ensure that a Bay of Pigs type incident would not occur again. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, the administration was again tested in its ability to interpret intelligence into policy; but this time, Kennedy himself ensured he called upon a council of ‘knowledgeable’ men to solve the potentially apocalyptic problem. The humiliating failure of the Bay of Pigs caused a presidency in its infancy to grow quickly into a capable and accountable administration. The outcome of the Bay of Pigs reflected poorly on the Kennedy Administration, but ultimately, the administration turned lemons into lemonade. Proving months later, during the Cuban Missile Crises, both the presidency and intelligence community were capable of countering Soviet influence in the western hemisphere, and rapidly improve the policy intelligence connection. −15− REFERENCES English, Joe R., Major, USMC, (April 1984). The Bay of Pigs: A Struggle for Freedom. Retrieved November 21, 2004 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/EJR.htm Kennedy, Robert F. (1971).Thirteen days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton &Company, Inc. Pentagon: Ninth Meeting. (May 1961). Memorandum for Record: Paramilitary Study Group Meeting. Retrieved on November 14, 2004 from http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB29/03-01.htm Persons, Albert C. (1990). The Bay of Pigs. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. US Central Intelligence Agency. (March 1961). Proposed Operation Against Cuba.. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.paperlessarchives.com/baypigs.html Warner, Michael. (1999). The CIA=s Internal Probe of the Bay of Pigs Affair. Retrieved November 14, 2004 from http://www.cia.gov/search?NS-search-page=document&NS-rel-doc-name=/csi/st udies/winter98_99/art08.html&NS-query=bay+of+pigs&NS-search-type=NS-boo lean-query&NS-collection=Entire%20Site&NS-docs-found=47&NS-doc-number =1 −16− −17− −18−