Africa in Documentary: A View from the Middle

advertisement

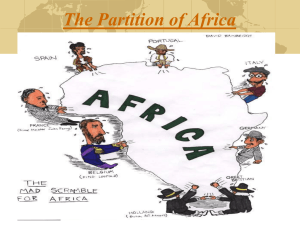

Africa in Documentary: A View from the Middle Farouk Musa Isa faroukmusaisa@gmail.com https://yasar.academia.edu/FaroukMusaIsa June, 2013 Faculty of Communication, Yaşar University, İzmir – Turkey Abstract The relationship between the western world and others (Africa, Asia, and South America), according to post-colonial theories, is based on the former dominating and thus exploiting the latter politically (through colonization and neo-colonialism policies), economically (by using capitalist system of economy), and culturally (through imperialism). In order to dominate the third world countries politically, economically, and culturally during colonial era, and to retain their influence in contemporary period, the West must impose their culture and traditions upon their erstwhile colonies. This was achieved through various means, among them is reinventing the history of the colonized nations. Like in other parts of the third world, the history of Africa documented by the so-called European discovers, explorers, traders, missionaries, and colonial masters had been utterly distorted by associating it with gruesome myths. The Herculean task to paint the clear picture of Africa by critics of the West had also been biased. The history of Africa and Africans, like any other societies, must be objective; neither like Eurocentric version, nor like that of their Africanists opponents. Keywords: African documentaries, Cultural imperialism, Eurocentric scholars, Anti-Eurocentric scholars Introduction Despite the negative portrayal of Africa, and the third world countries in general, by the Western media and via documentaries and other printed materials by Eurocentric scholars, PanAfricanist scholars argue that, still there is a hope for the so-called ‘dark continent’ to develop. As evidently noted by such scholars, the term ‘dark continent’ was invented by European colonizers in their efforts of covering the gruesome history of Atlantic slave trade, and justify what they did during slavery days, and to also justify their colonial policies, through showcasing Africans as uncivilized people, who deserved what had happen to them.1 1 Mirzoeff, N. (2009), An Introduction to Visual Culture, second edition, London: Routledge, p.128. In the mid-nineteenth century, when Western countries were obsessively searching for colonies in Africa, Asia, and South America, they reinvented the history of such ‘new’ colonies, so as to get support of the people to be colonized and the support of the entire world. In order to get the support of Africans, colonizers tried to impose their cultures upon the African, so as to change the way they (Africans) think and the way they act. The portrayal of the Western culture as superior, and the ‘need’ for ‘Others’ to abandon their own long inherited culture and join the bandwagon is termed as ‘cultural imperialism’. For colonizers, the support of the big nations around the world such as the defunct USSR and China was imperative. The reinvented history of Africa which described Africans as primitive, was a means of winning the support of big nations for the West to rescue the unknown but recently discovered ‘dark corner of the world’. The ‘new’ history of Africa from Eurocentric point of view was full of myths. For example, the European ‘adventurers’ ‘discoverers’ of Africa documented that the people living in Africa were nothing but barbarians and cannibals. The emergence of a body of historians and literary critics around the globe known as Anti-Eurocentric or Africans Arise scholars may become a challenge to the authors of what these scholars seen as ‘European distorted version’ of African history. Those Anti-Eurocentric scholars assigned themselves the Herculean task of presenting to the world what they see as the real history of the Africa through writings and making documentaries. The most Pan-African academia among them include Basil Davidson, a British historian, the producer and presenter of the documentary series, ‘Africa: A Voyage of Discovery with Basil Davidson’; Ali A. Mazrui, the Kenyan scholar and filmmaker of another popular documentary series entitled ‘The Africans: A Triple Heritage’; Henry Louis Gate, Jr., an American critic who is also the documentary filmmaker of the last in the trilogy, ‘Wonders of the African World’; Walter Rodney, the author of the well-known book, How Europe Under-develop Africa; and, Thomas Pakenham, the author of The Scramble for Africa. Aims As a historical analysis, the main aim of this article is to analyze the way in which Eurocentric scholars in one hand portray Africa, and how Anti-Eurocentric scholars on the part, challenged them. By looking at the history of Africa, both in written and in documentary, through the eye of post-colonial theorists, the author of this study however tries to adopt alternative point of view between the two opposing bodies of intellectuals: the opponents and proponents of the West. Literature Review Documentaries on African history usually focus on themes such as slavery, colonialism, civilizations, decolonization, neo-colonialism, and imperialism. These three premier video series regarding the history of Africa could serve as an example: first, the Davidson’s ‘Africa: A Voyage of Discovery’; secondly, ‘The Africans: A Triple Heritage’ by Ali Mazrui; and lastly, ‘Wonders of the African World’ by Henry Louis Gate. These three video series provide a rich and in-depth history of Africa. In ‘Africa: A Voyage of Discovery’, for example, Davidson created a documentary series which is clear and easy to follow. Africa: A Voyage of Discovery, as Keith Trnka and Kavita Vora (2000) perceptively argue, tell the history of Africa in such a way that “allows scholars and the general public to become more knowledgeable on the subject”. Concerning the richness in terms of information, Trnka and Vora firmly believe that in Africa: A Voyage of Discovery “Davidson tells us much about Africa and its past. He uses a variety of sources such as archaeological evidence, historical facts, interview, and quotes from ancient diaries of Africans and foreigners”.2 Using scholarly, scientific methodology makes Africa: A Voyage of Discovery particularly persuasive as well as impressive. Trnka and Vora succinctly sum it up, saying that “the vast resources he used support each of his arguments, making it difficult for another scholar to disagree with his findings”. The perfection of A Voyage of Discovery was not limited only to using scientific methodology and presenting facts, this series has entertainment value. Trnka and Vora argue that for anybody who has interest in Africa, Davidson's documentary will retain their attention. “This elderly British documentarian”, they write, “may not attract younger viewers who do not initiate the experience with an open mind. But, it was a fascinating journey through Africa which anyone could appreciate and enjoy”. 3 In general, Africa: a Voyage of Discovery outlines the overt and covert racism that has framed the European view of African history: This series seeks to open the eyes of those who have been lied to. In order to help bolster the wholesale dehumanisation of Africans (i.e. the Atlantic Slave Trade), Europeans in the 1600s and 1700s began to re-create history – suppressing that which was commonly known for centuries before – that Africa was the home to great ancient civilisations, societies and kingdoms. 4 2 Trnka, K. and Vora, K. (2000), Africa: A Voyage of Discovery With Basil Davidson, http://dickinsg.intrasun.tcnj.edu/films/basil/index.htm 3 Trnka, K. and Vora, K. (2000), Africa: A Voyage of Discovery With Basil Davidson, http://dickinsg.intrasun.tcnj.edu/films/basil/index.htm 4 Shocking: European Distortion of African History, http://thebbookplace.com/2010/11/03/shocking-europeandistortion-of-african-history/ It has eight different parts, and each part is further divided into subsections as follows: the first part is called “Different But Equal,” and it focus on the myths about Africa, the Green and Brown Saharas, Egypt, Nubia and Musovalat kingdoms, the Nuba Hills, and the Christianity. The second section of this documentary, “Mastering of a Continent” tell the history of the Pekot of Kenya, the Suka of Nigeria, and that of the Dogos of Mali. “Caravans of Gold”, as the third section called gave an in-depth history Mali, Ashanti Empire and Niger River, Timbuktu and Burbon Nomads, and the city of Cairo. The fourth section, the “King and The City”, dealt with the history of two prominent kingdoms of Benin and Kano. One of the important parts in this film was called “The Bible and the Gun”, and it covers issues of racism and slavery in Africa, and it looked on the coming of the so-called explorers and the missionaries, and the opening of missionaries’ training schools, and lastly the British conquest. Davidson called the sixth part of Africa: A Voyage of Discovery “The Magnificent African Cake”, and it has five sub-sections, namely: ‘Scramble for Africa’, ‘Britain’, ‘France’, ‘Portugal’, and ‘Beginning of Resistance’. In the seventh part, Davidson tells us about the rise of nationalism across the African continent, putting emphasis on Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), Kenya and Nigeria, Algeria, Congo and Mozambique, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and South Africa. The last section, titled “The Legacy”, is further divided into six sub-parts: ‘Lagos, Nigeria’, ‘European Models of Government’, ‘War in Nigeria’, ‘Economic Troubles’, ‘Independent Mozambique’, and lastly, the ‘Concluding Remarks’. In narrating the story of Africa in documentary, Mazrui is authority. His series, just like Davidson’s, combined compelling narratives and engaging visuals. For a more emotional effect he sometimes used music. Overall the series was interesting and thought-provoking: Mazrui's theme of the triple heritage gives a framework to the whole series. While he may not cite each of his sources, his findings are nevertheless based on historical facts. On the basis of these facts, he creates his own interpretation, which in turn addresses the issues and themes he discusses. 5 However, not all anti-Eurocentric scholars’ work is perfect. In the Wonders of the African World, “Gates gives glimpses into present day Africa, while going more in depth into its past. Though his aim seems to be to educate and entertain, we do not get a complete picture of Africa. It seems that some parts, while entertaining, lack depth”. The harshest criticism of Gates video series comes from Trnka and Vora (2000). They observed that: Gates seemed to lack organization in his presentation. We followed his route throughout Africa, and learned the history of the visited areas along the way. If Gates had a thesis, it was not clear in his film series. There were also several instances where his role as documentarian seemed to change to an American tourist. Rather than facilitating an objective view of Africa, its cultures, and its people, he imposes Western judgement on his observations. While a scholar should try to remain as objective as possible, Gates constantly reiterates that he is an African-American and gives us his subjective interpretations. 6 5 Trnka, K. and Vora, K. (2000), Africa: A Voyage of Discovery With Basil Davidson, http://dickinsg.intrasun.tcnj.edu/films/basil/index.htm 6 ibid They finally observed that though Gates’ approach is simple and directed toward a general audience, making the series attractive to the novice; and his aim seems to be to educate and entertain, still “we do not get a complete picture of Africa. It seems that some parts, while entertaining, lack depth”.7 Discussion The Europeans’ desire to acquire and expand colonial territories in African continent, which was known as ‘the Scramble for Africa’, and the need for them to maintain their grip on such territories, so as to satisfy their capitalist desire of acquiring mass wealth, through any means ranging from physical war and psychological one like the use of ‘divide-and-rule policy’, were the contributing factors for ‘reinventing’ the history of Africa. Modernity, cultural imperialism, acculturalization, and deculturalization are all by-product of colonial conquest that heralded the modem world. Colonialism or colonization, as V. Y. Mudimbe pointed, basically means organization or arrangement. It was derived from the Latin word colere, meaning to cultivate or to design (Mudimbe, 1988:14). During that period of colonization, or the ‘civilizing task’ as colonizers and Western historians describe it, the history of Africa had been ‘rewritten’ by showing the superiority of Whites over Africans, or rather ‘White supremacy’, using Paul Gilroy’s term. According to Hodgkin, quoted by Mudimbe, the fabricated version of history of Africans by colonizers described a pre-European Africa as a place “in which there was no account of Time; no Arts; no 7 ibid Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continued fear, and danger of violent death”. During decolonization process around 1950s and early 1960s in most African territories, their leaders, Talton reports, gained greater political power under European rule: In the decades that followed independence, they worked to shape the cultural, political, and economic character of the postcolonial state. Some worked against the challenges of continued European cultural and political hegemony, while others worked with European powers in order to protect their interests and maintain control over economic and political resources. Decolonization, then, was a process as well as a historical period. Yet the nations and regions of Africa experienced it with varying degrees of success. By 1990, formal European political control had given way to African self-rule—except in South Africa. Culturally and politically, however, the legacy of European dominance remained evident in the national borders, political infrastructures, education systems, national languages, economies, and trade networks of each nation. Ultimately, decolonization produced moments of inspiration and promise, yet failed to transform African economies and political structures to bring about true autonomy and development. Anti-Eurocentric documentaries condemn what they considered as ‘cultural arrogance’ of the Eurocentric academia. Ellen Meiksins Wood describes her positions by saying that “Like any good socialist, I fervently believe that the struggle against racism, imperialism, and European "cultural arrogance" is absolutely essential to our project”. Scholarship, Woods believe, is available tool to be used by critics of West in combating Eurocentrism, and this effort, she declare, “has often produced extremely important results by challenging the idea—which comes in many different forms—that "the west" has always been, for one reason or another, superior to all other civilizations and is destined to remain so”. 8 In the widest sense, Wood writes, Eurocentrism can be understood as the implicit view that European societies and their cultures constitute the "natural" norm for assessing what happening in the other parts of the world. She further noted that (and none of the critics seem to deny what Wood said): No one can deny that there is such a thing as European "cultural arrogance," and we do have to accept that there are more than enough reasons to challenge conceptions of history that place Europeans at the center of the universe, to the detriment, or the exclusion, of everyone else. The idea of "Eurocentrism," for all its faults, should at least put us on guard against such cultural practices. 9 When criticizing their opponents, pan-African writers and documentarians are exaggerating or over-stating facts concerning the African history. Example of such exaggerated work, as evidently noted by Mudimbe, is “the Rousseauian picture of an African golden age of perfect liberty, equality and fraternity”. The alternative position on this debate, however, is the middle point of view which this author occupies. Agreeing with him, Paul Gilroy correctly observes that the modernism of the black people have its origin in a “well-developed sense of complicity of radicalized reason and white supremacist terror”. He further noted that “The experiences of black people were part of the abstract modernity to produce as evidence some of the things that black intellectuals had said about their sense of embeddedness in the modem world”.10 8 Wood, E. M. Eurocentric Anti-Eurocentric, http://www.solidarity-us.org/site/node/993 9 ibid 10 Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso. Conclusion The surging, ongoing debate between two large bodies of intellectuals, the supporters of the West and their critics, concerning the history of Africa through documentaries and other discourses on African societies and cultures, seems to be continuously becoming more noticeable, and is increasingly drawing more attention of the world academia. The documented historical accounts of Africa by European explorers, traders, missionaries, historians, and colonizers portray Africans as people without any civilization. From Eurocentric point of view, we could understand African societies as nothing but barbaric, cannibals, and savage, living in the “darkest corner of the world” or in what P. Boulle called the “Planet of the Apes”. Anti-Eurocentric scholars aggressively criticized this notion, and condemned the work of Eurocentric scholars and historians on Africa, and third world in general, accusing them of been biased and subjective. Documentaries made on the history of Africa by anti-Eurocentric scholars, notably Davidson, Mazrui, and Gates, showed that Africans, like any society in the world, have their own history and culture, traditions and customes, religion and civilizations. However, African societies, according to these pan-Africanist documentarians, are willing to accept any unsuspicious new ideas and innovations in this period of modernity. The works of the two opposing groups, however, lacked accuracy, and as such they become biased. Their accounts on Africa did not reflect the true picture of the continent and its people. In other words, they presented to the world was did not objectively mirror African reality in its totality. It was true that there are rituals and uncivilizing practices among some African people, but this is acts are too scanty to generalize the whole continent. Pan-African scholars were on right track on their arguments that colonizers used ‘Westernized Africans’ to achieve their colonial aims and goals, and this concept of ‘colonial goals’, however, gave birth to other debatable issues such as imperialism, orientalism, acculturalization, deculturalization, and so on. To reconstruct reality in the documentary of history of not only Africa but any society, there is a need to be objective and unbiased. To achieve this, in this author’s perspective, one has to be neither with Eurocentric intellectuals nor with anti- Eurocentric one, meaning to stay in the middle. References Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso. Gleijeses, P., (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Le Seuer, James D., (Ed.) (2003). The Decolonization Reader New York: Routledge. Mirzoeff, N. (2009), An Introduction to Visual Culture, (2nd edition), London: Routledge. Mudimbe, V. Y. (1988). The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Nkrumah, K. (2006). Africa Must Unite. London: Panaf. Nzongola-Ntalaja, G., (2002) the Congo: From Leopold to Kabila. New York: Zed Books. Springhall, J. (2001). Decolonization since 1945: The Collapse of European Overseas Empires. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Sarkka, T. (2009), Hobson’s Imperialism: A Study in Late-Victorian Political Thought. Jyvaskyla Studies in Humanities, 118 Worger, W, Clark, N, and Alpers, E., (Eds.) (2001). Africa and the West: A Documentary History from the Slave Trade to Independence. Phoenix, Arizona: Oryx Press. Online sources “Shocking: European Distortion of African History”, (January 8, 2008), Retrieved on May 21, 2013, from http://thebbookplace.com/2010/11/03/shocking-european-distortion-of- african-history/ Talton, B. “The Challenge of Decolonization in Africa” (n.d), in African Age Retrieved on April 30, from http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/essay-challenge-of-decolonization- africa.html Trnka, K. and Vora, K. (2000), Africa: “A Voyage of Discovery with Basil Davidson”, Retrieved on May 21, 2013, from http://dickinsg.intrasun.tcnj.edu/films/basil/index.htm Wood, E. M. “Eurocentric Anti-Eurocentric”, (May/June, 2001), Retrieved on May 7, 2013, from http://www.solidarity-us.org/site/node/993