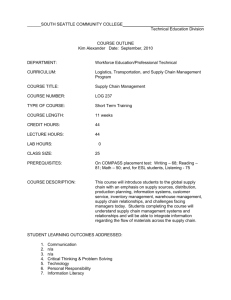

Logistics Management Units: What, Why, and

advertisement