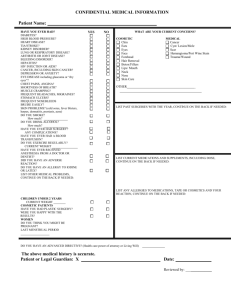

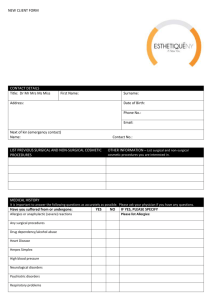

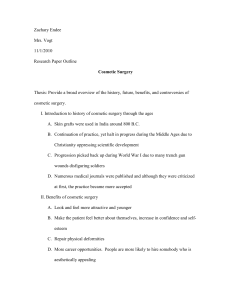

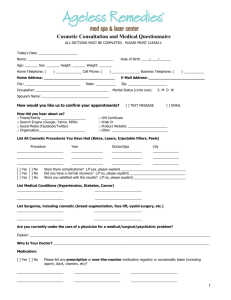

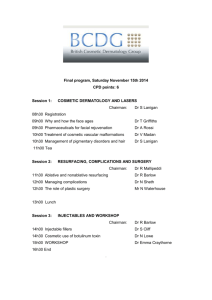

Cosmetic Medical and Surgical Procedures

advertisement