Women and Genital Cosmetic Surgery

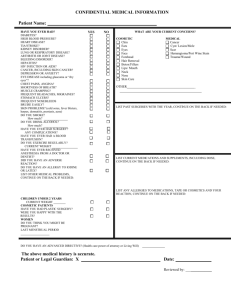

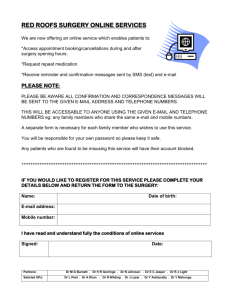

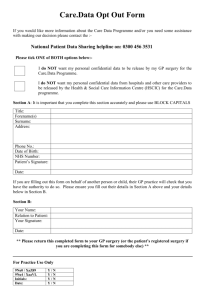

advertisement