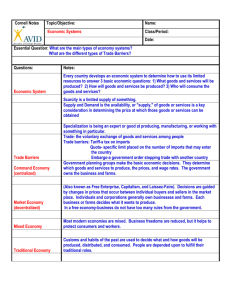

Chapter 8 The Structure of the United States Economy

advertisement