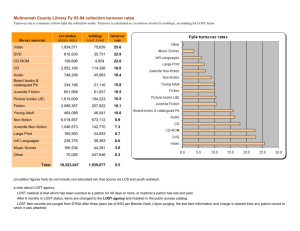

Turnover and retention

advertisement