TFM-Itziar Mojarrieta Sanz - Universidad Complutense de Madrid

advertisement

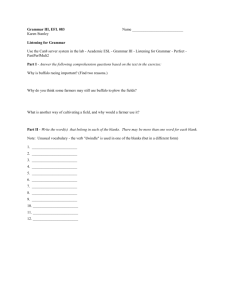

INDEX 1. Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 2. MA Dissertation rationale …………………………………………………………….. 3 3. Objectives ……………………………………………………………………………….. 5 4. Review of literature …………………………………………………………………….. 6 5. Methodology ……………………………………………………………………………. 12 6. Analysis of the results ……………………………………………………………….. 25 7. Conclusions …………………………………………………………………………….. 36 8. Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………………. 39 9. Appendix ………………………………………………………………………………… 42 1 1. Abstract Several literature and researchers talk about the benefits of working cooperatively in teams. For years, they have been investigating on the influence that a more socialised way of learning would have on the level of students’ comprehension. In a current context where autonomy is seen as one of the greatest abilities to achieve, more schools are following innovative teaching schemes designed with this aim. It is undoubtedly true that autonomy is a competence to improve during the scholarship period of any student, but also social conduct and team work are activities that any pupil should improve as they will have to face situations in this context in their future life. Moreover, motivation, especially with young students is a key element to consider when designing a teaching method in order to make it successful. Furthermore, especially focused in English classes, when dealing with a new language a socialised scheme should be considered necessary, as language is a tool for communication, and this one can happen in a socialised context. This paper introduces the concept of collaborative learning as a useful tool for enhancing students English comprehension. Collaborative learning in this research has been understood as a team-based learning scheme. More specifically, its main objective is to test the positive impact that this method would have in terms of motivation and improvement in grammar knowledge. In order to accomplish these objectives, the sample, composed by 49 participants belonging to third year of E.S.O., has been subject to a pre-test on both variables studied (motivation and grammar competence), a period of instruction in which team work has been developed, and one more test after that period, in which again both variables have been measured Outcomes are expected to show that there is considerable evidence to demonstrate the positive effect of this method in the student’s level of English comprehension. Key Words English teaching, Motivation, Grammar, Project Work, Individualised learning, Group work, Collaborative learning, Key competences. 2 2. MA Dissertation rationale Different literature talks about the benefits of working cooperatively in teams. Most of the authors who I refer to in section 4 support this idea: Dewey, Kilpatrick, Charters and Bode (the classical authors who formulated the project-work method applied in this Master’s Dissertation, talked about the importance to fill in the gap between school and society); this idea was also shared by Waks, L. J. who summarised it in 1997. Other examples are Núria Vidal (who according to Antonio R. Roldán Tapia (1997) acknowledged the importance of the communicative learning method), or Tom Hutchinson (2001) whose ideas are briefly explained in the aforementioned section. After visiting the innovative school assigned to me as part of my teaching practices, I decided this idea could work there, and also benefit my teaching experience. This school had a very innovative teaching system, based on a methodology called Basic Interactive Education (EBI Spanish acronym) which encourages students’ autonomy. This system does not use master classes as a way of transmission of knowledge, but a personalised syllabus which is comprised of subjects which are composed of what they call guías (guides). These guides include the instructions the students have to follow to achieve the key competences the teacher has established for each unit. From 5th year of Primary Education students have access to their syllabus through a web platform, specially designed for this system. Teachers arrange appointments with one or a small group of students to solve any doubts which have arisen during the execution of the guide. According to that program, each pupil evolved through the course lessons in their own timelines and usually worked alone, with the unique support of the teacher and a computer, and with fewer opportunities to interact among his classmates. From a general point of view, the method could had many benefits, as students could work as if they were doing their homework, so pupils could do other things later, such as: practising sport, learning other languages, or simply spending more time with their families and neighbours. Nevertheless, it had also some drawbacks such as loss of shared learning and interaction that could help to motivate the pupils. In this context, I thought it could be interesting to work with the students, in a more classical and socialised way, giving them some topics to develop together during the English class once a week. This way, pupils could benefit from each other. 3 The proposed teaching method was well accepted in the school, and the classroom of 3rd year of E.S.O. students was the targeted group to test it. The design of the teaching method (more information can be found at section 5) took into account the key competences included in the Recommendation 2006/962/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning [Official Journal L 394 of 30.12.2006], “Key competences for lifelong learning are a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes appropriate to the context. They are particularly necessary for personal fulfilment and development, social inclusion, active citizenship and employment.” Key competences should be acquired at the end of the students’ compulsory education. Among the eight key competences (communication in the mother tongue, communication in foreign languages, mathematical competence and basic competences in science and technology, digital competence, learning to learn, social and civic competences, sense of initiative and entrepreneurship and cultural awareness and expression), the following were developed and acquired within this teaching unit through the following activities: - communication in foreign languages: reading authentic texts from Britannica Online for Kids and BBC Food, transferring what they have read through a presentation, listening to their classmates, listening to a song in English, etc. Materials: Music: worksheet 1, Music: group 1-5, Ireland (group 1), Northern Ireland (group 2) , Scotland (group 3), Wales (group 4), England (group 5), Colcannon (group 1), Irish beef stew (group 2), Haggis (group 3), Welsh rarebit (group 4) and Roast beef (group 5). - mathematical competence: understanding the value of English measurement units, such as: pound (lb.), ounce (oz), pint, tablespoon (tbs.), etc., while reading a recipe. Materials: Colcannon (group 1), Irish beef stew (group 2), Haggis (group 3), Welsh rarebit (group 4) and Roast beef (group 5). - basic competences in science and technology: finding on a map the city or region where a band or a singer is from, knowing the biggest British Isles (Great Britain and Ireland) and the four countries of the United Kingdom plus Ireland. Materials: maps. - digital competence: visiting the official webpage of some bands or singers in order to gather the information needed and looking for information about some sightseeings in the Internet. - learning to learn: searching for information on their own, data processing and presentation. 4 - social and civic competences: respecting classmates’ (musical) preferences, understanding cultural differences (typical dishes from other countries), participating, in a respectful way, in group work, etc. - sense of initiative and entrepreneurship: suggesting topics for the projects, planning and managing them, and suggesting changes and own preferences. Materials: Questionnaire (Ramón Ribé & Núria Vidal 1993). - cultural awareness and expression: appreciating musical and gastronomic culture, enjoying listening to songs in English, and designing a poster. 3. Objectives The main objective of this research work is to prove the positive effect of the collaborative learning by means of two project works in student’s English comprehension. Project works have been designed with the objective that pupils socialise more, and enjoy learning English at the same time that they revise some grammar points which they have to improve. Some other objectives related to the first one are the following: - to revise some grammar units through the project-work method; - to know and appreciate some aspects of the English and American culture: music, food, different measurement units, and names and the location of some cities of the United Kingdom and the United States of America; - to understand original texts in English, using monolingual dictionaries and glossaries, and to learn how to use the dictionary; - to talk about their musical preferences; - to read and search for information about music and food; - to locate a city on a map from the USA or UK; - to listen to a song in English, just for pleasure, and understand most of it; - to learn some differences between USA and UK; - to be aware of the English measurement units (lb., oz, pint...); - to understand a list of ingredients of an original recipe; - to be able to read and fill in a questionnaire in English; - to have fun at English class thanks to this method, preparing a presentation; - and to give them enough chances to express themselves in English and to talk about motivating and interesting topics. 5 4. Review of literature This review covers the following points: first Spanish work on project work; a review of the classical formulation of project method in the United States (Dewey, Kilpatrick, Charters and Bode), a review of the projects developed in Spain during the 1980s and the 1990s, and Leonard J. Waks’ and Antonio R. Roldán Tapia’s proposals on this teaching method, which were published in their articles: ‘The project method in postindustrial education’ and ‘El trabajo por proyectos en el sistema educativo español: revisión de propuestas de realización’, respectively, both published in 1997. According to Antonio R. Roldán Tapia1 (1997: 116), the project method has its origin in Spain during the Spanish Second Republic (1931-1939) when F. Sáinz -following in the American (Kilpatrick and John Dewey) and the European (Decroly and Célestin Freinet) precursor‘s footsteps- published El método de proyectos in 1934. As Roldán states (1997: 116), Sainz’s theory is based on the idea of activity opposed to the idea of passive learning within an educational system characterized by memorisation. Let us have a look at Dewey’s and Kilpatrick’s formulation of the project method and the early US debate about it, through Leonard J. Waks 2 ’ article ‘The project method in postindustrial education’. To start with, I would like to add a quotation from Jane Addam’s work Democracy and Social Ethics (1902) taken from Waks’ article which, from my point of view, perfectly evokes the feeling of lost which led to the devising of the method. ‘The domestic arts are gone, with their absorbing interest for the children, their educational value, and incentive to activity... For the hundreds of children who have never seen wheat grow, there are dozens who have never seen bread baked... The child of such a family has little or no opportunity to use this energies in domestic manufacture, or indeed, constructively in any direction’. Probably Adams’ last sentence is too pessimistic, but the truth is that as Waks states (1997: 391), ‘the organisation of learning in projects under learner control was a major theme of 1 English teacher at Alhaken II secondary school in Córdoba (Spain) and teacher trainer. (Information taken from his blog) 2 Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at Temple University 6 early twentieth century American philosophers of education and curriculum theorist’. According to him (Waks 1997: 391), ‘school-based projects under learner control first gained a foothold in the USA in technical and agricultural education at the end of the nineteenth century’ and it was thanks to John Dewey’s work The School and Society that they ‘were given added legitimacy in general education’. Nevertheless, as Waks’ article explains (Waks 1997: 391), Dewey’s work was just a seed to sow and ‘projects were elevated to the status of a general method by William H. Kilpatrick, and had a profound influence educational practice in the USA, Europe, and even the Soviet Union (Dewey 1984, 1990).’ Taking again into account the feeling of lost evoked by the above-mentioned Adams words, we could better understand that (Waks 1997: 395) ‘in taking up the slack, teachers soon discovered that school routines (lectures, demonstrations, recitations) designed for training in basic literacy and conventional school subjects were ineffective for these new tasks. They started experimenting with learning projects in schools simulating conditions and tasks in home and at work.’ According to Waks (1997: 395), Dewey “accepted the benefits claimed for these innovations by their founders; that they engaged the interest and attention of students, keeping them alert, making them more capable and better prepared for adult life. (...) But he also found such stated benefits ‘unnecessarily narrow’ (Dewey 1900: 14, 15-16, 18) because of their individual focus”, and he ‘understood clearly that skills acquired in industrial and domestic arts classes would find little direct application in industrial work places’ and also that ‘the introduction of ‘more active, expressive, and self-directing factors’ in the schools, and the ‘relegation of the merely symbolic and formal to a secondary position’, signalled a necessary evolution to social life.’ (1997:395). As Waks states (1997: 396), it was Kilpatrick who organised the aforementioned factors, undertaking the task Dewey delegated to future scholars. In 1918 Kilpatrick’s work Teachers College Record defined project as ‘a wholeheartedly purposeful activity carried on in a social context’ 3 and, as Waks (1997: 396) states, ‘he argued that the project, so defined, could be made the organising unit of all school learning, hence the idea of a project method. According to Waks’ explanation (1997: 396), “to make the learning project into a general method of school education, Kilpatrick sought the broadest possible interpretation of the term ‘project’, noting that ‘projects may present every variety that purposes present in life’”. As he also explains, this ‘wholeheartedness’ and ‘a social context’ - ‘value judgement through the consideration by peers’ (Walks 1997: 396)- were the two main conditions of Kilpatrick’s analysis, which identified four different types of projects: 3 the definition is taken from Waks, 1997: 396 7 ‘(1) those where the purpose is to embody some idea or plan in external form; (2) those where the purpose is to enjoy some experience; (3) those where the purpose is to straighten out some intellectual difficulty – to solve some problem; and (4) those where the purpose is to obtain knowledge or skill.’ (Waks, 1997: 397). According to Waks’ article, three years later, J. A. Steveson redefined the term project and in 1923 W. W. Charters found Kilpatrick’s definition of project too broaden and also provided a new one; ‘a problematic act carried to completion in a natural setting’4. In 1925, Kilpatrick’s Foundation of Method was published. According to Waks (1997: 399), it “consisted of an amplification of the ideas in his original ‘project method’ paper and a consideration of the criticisms it provoked”. As Waks explains (1997: 399, 400), Kilpatrick “tenaciously stuck to his guns on the centrality of the ‘wholehearted purpose’ condition in defining ‘projects’”; but ‘he distinguished two senses of ‘purposing’, or ‘having a purpose’, corresponding to (a) doing what you like and (b) liking what you do, and opted for the second as definitive of projects’. In Kilpatrick’s words, ‘If the purpose dies and the teacher still requires completion of what was begun, then it becomes a task.’5 As Waks states (1997: 400), in 1927, Kilpatrick’s method was again revisited by Boyd Bode, who ‘began his consideration of the project method in Modern Educational Theories (1927: 145) by affirming its primary motivation: the desire to close the gap between school and outof-school life’. According to Waks (1997; 401), Bode thought that Kilpatrick “had attempted to redefine ‘projects’ in terms of the attitudes of the learner towards his activity”, and ‘as this attitude of wholeheartedness could be extended from projects in the initial and clear sense to all school activities, Kilpatrick’s approach appeared (by some magic trick) to have extended what was worthwhile in such projects (the attitude) to the rest of school learning’; moreover Bode argued that the incidental learning which resulted from the completion of project work was ‘too random, too haphazard, too immediate in its function, unless we supplement it with something else’. In Bode’s words, “‘project method’ has only introduced conceptual confusion and a ‘new attempt to solve educational problems by means of a magic formula” (Bode 1927: 165 in Waks 1997: 402). Nevertheless and in accordance with Waks (1997: 402), “Bode himself had no intention of questioning the educational value of projects under learner control. For Bode incidental 4 the definition is included in Waks, 1997: 398 5 Quotation taken from Waks (1997: 400) 8 learning was important and even ‘tremendously effective’. But it was also inevitably incomplete.” Going back to Europe and focusing on Antonio Roldán’s article, we are going to enumerate some of the main projects regarding the teaching of English developed in Spain during the last two decades of the 20th century. This enumeration is suitable as a review of the themes which were discussed during the last century and, along with the previous rationale, as a justification for this Master Dissertation. As Roldán Tapia states (1997: 116), regarding the teaching of English, the first project works were developed in the 1980s in Catalonia. This idea concurs with Diana L. Fried-Booth’s update of Project Work (2002: 5, 6) which states that ‘The original reason for developing project work at the beginning of the 1980s resulted from the impact of the communicative approach on what teachers were doing in the classroom’. According to Roldán’s review (1997: 116), Núria Vidal carried out a project work with C.O.U. students under the motto ‘Humanizing the classroom’. The experience was compiled and published in Barcelona in 1984. As Roldán Tapia states two years later, in 1986, M. Casañas described two projects (‘A visit to a hospital’ and ‘A trip to the isle of Skye’) which were carried out with 3º B.U.P. students, and M. Ravera and N. Vidal designed three teaching units occurred at the en of each unit (‘A personality game’, ‘The trip’ and ‘The island’). Roldán also mentioned two project works which Vidal did with 2º B.U.P. students during two different trips to England and which were published in 1987 and 1988 under the title ‘Account of a trip to Bournemouth, England, with I.B. students, the symbol of a dream accomplished with enthusiasm and effort’ and ‘The shadow in the mist’, respectively. All of these projects were published by the I.C.E. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Roldán Tapia also describes the project works carried out by I. M. Palacios Martínez in a Galician institute by 3º B.U.P. students which were compiled in 1988 by the publication Aula de Inglés. According to A. Roldán (1997: 116, 117), the themes of these projects were: a guide book of the student’s village, an audiovisual presentation of the village, British and Spanish press, American and Spanish basketball and la movida viguesa (cultural activity of Vigo, Galicia). By means of Roldán Tapia article, now we are going to continue this journey visiting the main projects within the English lessons of the 1990s in Spain. 9 In 1991 a project developed by M. López de Blas at the outskirts of Madrid, which was designed for E.G.B., B.U.P. and F.P. students around the topic comparatives and superlatives in English, was described in the publication TESOL-Spain Newsletter. In 1992, a project carried out in parallel in four different countries (England, Spain, Finland and Austria) was registered. The theme was ‘Our environment’ and the authors: A. Klee, N. Vidal, E. Syrjaelaeinen and K. Demetz. Two years later, in 1994, he (A. Roldán), M. C. Luque, J. Gallego, F. Sánchez and J. Tejederas described in the magazine of the Provincial Delegation of Education from Cordoba a project on music. Also that year Ramón Ribé described two project works carried out in Barcelona with C.O.U. students ‘The land of the green people’, aims and achievements during the students’ academic year, and a third project developed with 1º B.U.P. students whose theme was free. In 1995, I. Pérez Torres described a work with 16-18-year-old students from Granada; ‘A project in/about London’. Finally, in 1996 A. Roldán recorded the project work he carried out with 2º B.U.P. students the Worlds AIDS Day on that topic. Most of the project works mentioned above were developed with B.U.P. or C.O.U. students but, since in this Master’s Dissertation we are analysing the effects of two projects designed for and carried out by 3º E.S.O. students, now I would like to mention the ones carried out by Secondary students in Spain in the 1990s which A. Roldán recorded in the aforementioned article. In chronological order, these are: Two project works developed by students of 7th year of E.G.B. described by F. Rodríguez Torras; the first one on Hawaii and the second one on the discovery of America. According to Roldán (1997: 118), the project about Hawaii was more guided by the teacher due to the age of the students. J. M. Cabezas’ projects about ‘The Valentine project’ and ‘The food and drink projects’. The projects carried out by the Granada Learner Autonomy Group whose topics are not included in Antonio Roldán’s article. M. Olivera Tejedor’s project work on music, ‘The use of written material related to music’ published by TESOL-Spain Newsletter. M. P. De la Serna and A. Fernández, and P. Fernández Vez projects, both of them based on the use of the school environment to foster the students’ motivation. 10 Also Antonio R. Roldán refers to his articles ‘Proyectos en el ciclo 12-14: un modo de empezar’ and ‘Inglés y juegos de mesa: una experiencia con proyectos.’6 After this review of some of the project works developed in Spain and the themes that were discussed in the Spanish classrooms during the last century, I would like to mention some of the changes proposed by these authors. Antonio Roldán suggests some topics suitable for the 21st century students, arguing (1997: 119) that they are relevant to every human’s daily life. The topics he proposes are: human rights, the role of women, the environment, health and quality of life; and topics that deal with some of the cross-curricular subjects of the new Spanish Educational Law, such as: Education for Peace, Health Education, Road Safety Education, Education on Sustainable Consume, Coeducation, etc. Taking all of these into account, Roldán designed a project on the Worlds AIDS Day whose objectives and concepts (conceptual, procedural and attitudinal) are, as Waks states (1997: 121), in accordance with Hutchinson’s and with Eyring’s works published in 1991 and with Littlejohn’s idea of the “educational value of a project” which Waks briefly describes (1997: 121) and which I think Hutchinson also shares. In Tom Hutchinson’s words (2001: 11), ‘project work captures better than any other activity the two principal elements of a communicative approach. These are: a concern for motivation, that is, how the learners relate to the task; a concern for relevance, that is, how the learners relate to the language. We could add to these a third element: a concern for educational values, that is, how the language curriculum relates to the general educational development of the learner.’ Leonard J. Waks (1997: 404) also suggests some changes of the formulation of project work: a negotiation of the group product, a situation of the group project in a social context, an assessment of incidental learning potential relative to learner’s needs, a needs-assessment of background knowledge, a facilitation of project tasks and a project assessment and learning integration. 6 Both articles were written by Antonio R. Roldán Tapias and published in 1995 and in 1997 respectively. 11 Finally Leonard J. Waks (1997: 404) states that ‘(...) the problem is to lay a foundation of learning experiences, in the contemporary technological and economic climate, to prepare the community as a whole for a democratic shaping of the postindustrial order’. 5. Methodology This section covers a detailed description of the methodology that has been selected in order to test the formulated hypothesis of this Master’s Dissertation. The aforementioned hypothesis intends to prove the positive impact of collaborative learning through the project work method in student’s English comprehension. The rationale behind that supposition is described in detail at section 2. In order to test that, it is important to consider that one of the most important aspects when selecting the most suitable type of methodology to be applied in a research is to acquire enough theoretical knowledge that will help with the design of the best testing method. Moreover, that literature review can help to confirm the existence of similar hypothesis, which could have common grounds with the one intended to explore, and to identify different aspects to take into account when designing the testing methodology. A full description of this literature review can be found at section 4. In any case, it could be interesting to note some methodological principles which partially guided the design of the methodology. They were taken from “The Natural Approach” developed by Tracy Terrell and Stephen Krashen, and its communicative view of language: 1. Language acquisition is an unconscious process developed through using language meaningfully (in this case, while students are carrying out and presenting the different projects); 2. In order to avoid the affective filter hypothesis (the learner's emotional state can act as a filter that impedes or blocks input necessary to acquisition), teacher and classmates help shier students feel confident while speaking and errors are tolerated most of the times; 3. Errors must not be seen as faults, but as evidence of the learning process; 4.Target language is not the object of study but a vehicle for classroom communication (students present and transfer the knowledge they have acquired); 5. Fluent and acceptable language is the primary goal; 6. Authentic materials are used (materials from Britannica Online for Kids and BBC Food); 7. Students work in groups and help each other; 12 9. Students are negotiators between the self, the learning process, and the object of learning (they suggest topics, possible changes, etc.); 10. The teacher is a facilitator, an organizer of resources and a group process manager; 11. Classes are student-centered; 12. Collaborative learning is one of the teaching techniques used. According to this technique, small teams use a variety of learning activities to improve their understanding of a subject. Derived from the hypothesis, some research questions were raised: A. Does the project method and therefore collaborative learning increase students’ motivation in schools with a personalised learning system? B. Does this method increase their willing to learn and, therefore, the number of hours of learning devoted to this subject? C. Do students who interact in project works get better results in grammar? Apart from identifying the situation to be explored, defining the hypothesis to test, and establishing the research questions, additional work is needed in the identification of both, the dependent and the independent variables which are derived from the hypothesis, and in the selection of an appropriate sample to work with. The aim of this Master’s Dissertation is to test the effect of the collaborative learning by means of two project works in student’s English comprehension at English class in a privately-owned but state-funded school, with students of 3rd year of E.S.O. Moreover, it intends to explore the relationship and possible benefits between the use of this teaching scheme and the possible improvement in English comprehension, motivation and grammar knowledge. In order to do that, it has been crucial to firstly study the present circumstances (pre-project situation) found at the school of the sample selected to work with, since it is the only way to compare pre and post results. The study of that situation has been based basically on observation, carried out during the first period of the teaching practice, in January 2012. Once this situation was identified, several dependent (outcome variable which is caused by an input) and the independent (antecedent variable which causes an outcome) variables were noted. The picture below consists of a visual representation of both of them, which 13 have been involved in this research work, as well as the interrelationship that exists between them. Dependent - Students’ English comprehension. Independent - Motivation (self-confidence, interest in the topics...); - Grammar knowledge. Collaborative Learning Motivation Students’ English Comprehension Grammar knowledge Apart from the hypothesis and the variables, it is crucial to describe the participants who have been involved in this research. The participants who have taken part in this experiment belong to the same environment, what ensures results’ adequacy, since all students are influenced by the same independent variables. The sample tested is composed by students belonging to a privately-owned but state-funded school of Madrid, whose name is not going to be given as neither the names of the students taking part of the sample, trying to preserve the privacy that all researches imply. The students, apart from belonging to the same school, belonged to the same class. In this sense, the majority of the students have the same age being the average age 15/16 years old. As described in the pre-project situation, the fact that the students belonged to the same class does not obviously mean that they have the same level of English. This is due to the innovative teaching method applied at that school, based on an autonomous learning method developed individually by each pupil, with the unique help of the computer and some appointments arranged by the teacher eventually with one or a small group of students to solve any doubts which have arisen during the execution of their own learning method. After the observation week in January, I divided two classes into five groups formed by students with a medium, high and very high level of English, and almost by the same number 14 of young boys and girls. Regarding the level of English, groups were formed thanks to the marks assigned by my mentor. With regard to the number of boys and girls, they were assigned to the groups randomly. The sample is composed by 24 students in each class, including both males and females. The sample was designed according to the aforementioned criterion in order to make it homogenous, to ensure the validity and reliability of the results of this research. Sample Group • Two 3rd year of E.S.O. classrooms (of 24 and 25 students) • Subject: English • Length: 7 lessons (one lesson of 50 minutes per week, from the 23rd of March until the 18th of May). Class I worked with this method on Wednesday from 12 to 12:50 and Group II worked on Fridays from 10 to 10:50. • Number of groups in each class: 5. Each group was formed by weak and stronger students in English, so that the weaker ones take advantage of their classmates. Another benefit was that they will socialise more (in the pre-project situation two days a week they work in different classrooms) and thus motivation could increase. Thanks to this new teaching scheme students could work one day per week cooperatively (bright and weak students together) on the key competences and on common topics related to the English world. So that weaker students could take advantage of this situation and could learn from their peers. Since they were divided into two different levels and two days a week they worked in different classrooms with a native English teacher, they could also socialise more and the project would be more easily developed. Finally, a particular methodology has been chosen and some materials were needed to be used. Firstly, the materials used to test the hypothesis have involved: • Personal resources: the students • Environmental resources: free unlimited Internet access (WiFi system) and six big tables, where groups of four or five students were able to work together. Students could bring their laptop (they usually worked with it) and used it as a research tool for the activities proposed during the project. The classroom used to have a digital whiteboard which was removed during the process of the project and was not replaced neither with a new one or with a common white or blackboard. Because of 15 that we worked with pictures and posters. The classroom was also equipped with a cassette with CD player, which was used during the project on Music. • Curriculum-related materials: Since, due to the school’s system, most of the students worked on different units and the aim the project method was to work with the whole class, we didn’t use any textbook. Two project works were developed. Original materials were designed from webpages and two books, which will be mentioned at section 8. A monolingual dictionary was available as well as some glossaries which were also designed by me because of the complexity of the texts. Finally, other materials used to test the hypothesis have been three tests, used to evaluate the results of the teaching method applied. A full description of them is detailed at the end of this section. • ICT resources: Laptops were used as research tools. Picture 1: Examples of materials: pictures and posters Secondly, the particular teaching methodology involved two project works: one on Music and a second one on Food (Project Work 1: Pop music, and Project Work 2: UK & Ireland: Typical dishes). Initially a test on “topics of interest” was thought to be circulated among the students, but due to time constraints the selection of the topics was done by me taking into account general culture related to the English world. Although both project works were initially designed to be tested with the two classes, the two projects were only finished with Class I (24 pupils). With Class II (25 pupils) only the first project work caused enough enthusiasm among the students, thus the second was not developed, in any case grammar theory related to that second project work was explained. 16 Seven sessions were devoted to this research, in addition to the observation of students’ improvements during my mentor classes. First session was devoted to explain students the aim of the research, and to briefly inform them about rights, protection & liabilities. I also passed a motivation and a grammar test. During the next five sessions two projects works were carried out, and pupil’s final work was presented at the end of each of these projects. The last session was devoted to pass a final test and to receive feedback about the project works. Project works enabled the fulfilment of a common task among students who usually work at their own pace on different units. Students also enjoyed learning English at the same time they revised some grammar points they had to improve. The content of the project works was designed based on the lacks identified thanks to a pre-project test on grammar circulated among the students in the first session. Project works contained a worksheet with reading (R), listening (L) and grammar exercises. They also included a task based on the preparation of a presentation where each member of the group should take part, and also with writing exercises (W) as they had to prepare the outline of the presentations. This way, students improved their speaking (S) and listening skills, as some questions were included so that the rest of the class should pay attention to their classmates’ presentation. Reading, listening, writing and speaking were skills to be improved by means of the project works. These skills were improved collectively as students had to work in groups. Nevertheless, the assessment of this teaching methodology was designed to be measured only by a grammar post-test based on the grammar worksheets, which the students had to work with. 17 The following tables show a brief description of the project works that have been used in order to prove the main hypothesis, which was to investigate about the influence of the collective learning in students’ English comprehension. For detailed information on the project works, please see the correlated document Practices Aid Memory (Memoria de prácticas). SESSION 1: 23rd March Step Activities (time) 1. (5 m.) 2. (10 m.) 3. ( 30 m.) 4. (5 m.) Explain students the aim of the questionnaire and the grammar test. Activity 2 Fill in the following questionnaire on motivation in English. Activity 3 Do the following test. Explain students that once a week from now until the end of the course we are going to work on some projects. Suggest music as the first topic. Communication (functions) --- Language (gram, vocab, pron) --- --- --- - Revising grammar points they have studied during the first and second term. Grammar: Present simple, present continuos, past simple, there was/were, too much/many, comparatives & superlatives, and first conditional. Skills L S R X X X W Grouping C G P X X Materials I --- X --- X Diagnostic test X 18 th SESSION 2: 13 April Step Activities (time) 1. Activity 1 (5 m.) Warm-up: Do you like music? What type of music do you like the most? What do you know about pop music? 2. Activity 2 (15 m.) a) A volunteer or the teacher reads the first two paragraphs; b) In pairs, fill in the gaps; c) Check it as a whole-class activity. 3. Activity 3 (30 m.) Preparing the presentation. In groups of 4 or 5, read the texts assigned to your group. With the information given and after visiting the official website of the artists/bands, locate their birthplace on the map and write an outline of what you are going to present in front of the class. Use the dictionary and/or the glossary. If you want, you can bring a song to class. Each member of the group should take part in the presentation. st Suggestion: student 1 (1 music style), student 2 (singer/band), nd student 3 (2 music style), student 4 (singer/band), and student 5 (map & song). Communication (functions) - Talking about musical preferences Language (gram, vocab, pron) Skills L S X X R - Relating what they said about pop music to its definition. - Past simple of some irregular verbs; - Vocabulary on music (musician, rhythm, performer, trend, bass, low and high notes, etc.) - Past tense - Vocabulary on Music X X - - - Reading and searching for information about music. Locating a city on map from the USA or UK. Preparing a presentation, writing an outline in groups. X W Grouping C G P X X X Materials I POPULAR Music: worksheet 1 X X X Music: group 1 Music: group 2 Music: group 3 Music: group 4 Music: group 5 Dictionary music-glossary 19 SESSION 3: 20th April Step Activities (time) 1. Activity 1 (5 m.) Warm-up: Get ready to present your music style and singer/band in front of the class. 2. Activity 2 (5 m.) Present your music style and artists. a) Presentation group 1: blues & surf rock 3. (20 m.) 4. (15 m.) Activity 3 a) Presentation group 2: British invasion & psychedelic rock b) Worksheet 2: b.1.) Compete the following table in pairs (comparatives and superlatives). b.2.) Listen to the song and fill in the lyrics individually. Activity 4 a) Presentation group 3: progressive rock & singer-songwriters; b) Presentation group 4: Disco & glam rock; c) Presentation group 5: punk & heavy metal; Communication (functions) -- Language (gram, vocab, pron) -- Skills L S - Explaining and transferring information; - Listening to classmates’ presentations. - Explaining and transferring; - Listening to classmates’ presentations; - Revising the comparatives and superlatives; -Listening to a song in English. - Explaining and transferring information; - Listening to classmates’ presentations. - Past tense - Vocabulary on Music X X X X - Past tense - Vocabulary on Music - Comparatives and superlatives X X X X - Past tense - Vocabulary on Music X X X X R W Grouping C G P X Materials I -- Music: group 1 DIN A1 card, maps, crayons and glue. X X Music: group 2 Music: worksheet 2; DIN A1 card, maps, crayons and glue. CD player Music: group 3 Music: group 4 Music: group 5 DIN A1 card, maps, crayons and glue. 20 th SESSION 4: 27 of April Step Activities (time) 1. Activity 1 (15 m.) a) end of presentation 5; b) listening to a song students brought while finishing and displaying the poster. 2. (10 m.) 3. (10 m.) 4. (15 m.) Activity 2 Warm-up: have a look at the map and see the places we are going to visit and their typical dishes. Have you ever been to one of these cities? Have you eaten one of these dishes? After reading the list of ingredients you might not now, complete the table below with the words in the box. Activity 3 a) A volunteer student or the teacher reads grammar reference A: too much, too many and enough; b) Do exercise 2 from the worksheet individually. Check it as a whole-class activity. Activity 4 a) A volunteer student or the teacher reads grammar reference B: zero, first and second conditional. b) Do exercise 3 from the worksheet in pairs. Check it as a whole-class activity. Communication (functions) - Explaining and transferring information; - Listening to classmates’ presentations. - Listening to a song in English, just for pleasure. -Understanding a definition in English. Language (gram, vocab, pron) - Past tense - Vocabulary on Music Skills L S X X - Vocabulary on food (ingredients). X X - Revising the use of too much, too many and enough. - Too much, too many and enough. X X - Revising the use of zero and first conditional. - Learning the use of second conditional (weak students) or revising it (strong students). - Zero, first and second conditional. X X R W Grouping C G P X X Materials I Music: group 5; DIN A1 card, maps, crayons and glue; Computer & loudspeakers; Student’s pendrive. UK & Ireland: booklet; UK & Ireland: worksheet 1 X X UK & Ireland: booklet; UK & Ireland: worksheet 1 UK & Ireland: booklet; UK & Ireland: worksheet 1 21 th SESSION 5: 4 of May Step Activities (time) 1. Activity 1 ( 5 m.) Warm-up: Do you know what does this map represent? (Great Britain vs. England) 2. Activity 2 ( 15 m.) a) Read the text individually. In pairs, answer the following questions and check the answers within your group. Complete the sentence “if I were in (...), I would visit...” using the second conditional and looking for a sightseeing in the Internet. b) If you want to prepare... Read the following recipe (just the ingredients). In groups, enumerate them and write two sentences using too much, too many and enough. Communication (functions) - Speaking about general knowledge: difference between Great Britain and England. - Reading and understanding a text (authentic material from Britannica Online for Kids and BBC Food); - Understanding the value of English measurement units (lb, oz, pint, tbs). Language (gram, vocab, pron) Skills L S X R X X -First and second conditional W Grouping C G P X X X Materials I Map X - Ireland (group 1) & Colcannon (group 1); -Northern Ireland (group 2) & Irish beef stew (group 2); If I were in (...), I would visit... If you want to prepare/cook (...), you will need - Scotland (group 3)& Haggis (group 3); -Vocabulary about food: pound (lb), ounce (oz), pint, tablespoon (tbs). - Wales (group 4) & Welsh rarebit (group 4); -Too much, too many and enough -England (group 5)& Roast beef (group 5) - Laptop (Internet) 3. (10 m.) Activity 3 Preparing the presentation: write, with your own words, an outline about your region and its typical dish. Each member of the group should take part in the presentation. Your classmates will have to answer to the same questions, so do not forget to include that information! - Writing an outline for a presentation. 4. (20 m.) Activity 1 a) presentation group 1; read and answer the following questions in pairs. b) presentation group 2; read and answer the following questions in pairs. - Explaining and transferring information; - Listening to classmates’ presentations and answering some questions. X X X Notebook X X X X X -Map, pictures of the typical dishes and glue. - UK & Ireland: worksheet 2 22 SESSION 6: 11th of May Step Activities (time) 1. Activity 1 (15 m.) Do the grammar post-test and answer the following questions about group work. 2. (10 m.) Activity 1 Group 3, 4 and 5. Revise your outline and get ready! Group 1 and 2: agree on a topic for the last project/suggestion for future project works and fill in the questionnaire. Communication (functions) - Speaking: to reach an agreement in English. Language (gram, vocab, pron) - Past simple; - Comparatives and superlatives; - Too much & too many; 1st, 2nd, 3rd conditional Skills L S X R X W X Grouping C G P X Materials I X - Scotland (group 3)& Haggis (group 3); X - Wales (group 4)& Welsh rarebit (group 4) ; - Reading and filling in a questionnaire in English. -England (group 5)& Roast beef (group 5); - Questionnaire (Ramón Ribé & Núria Vidal 1993) 3. (25 m.) Activity 2 a) presentation group 3; read and answer the following questions in pairs. b) presentation group 4; read and answer the following questions in pairs. c) presentation group 5; read and answer the following questions in pairs. X - Explaining and transferring information; - Listening to classmates’ presentations and answering some questions. X X X X - Map, pictures of the typical dishes and glue. - UK & Ireland: worksheet 2 23 In order to measure the results of the methodology, three assessment tests were passed to the pupils. Results were assessed before and after the teaching period. One of them was a specific test on motivation on English learning and the other two were grammar tests. Nevertheless, the second one included an activity related also to motivation, which would let me to evaluate results on this variable after the teaching period. MOTIVATION The first day a motivation questionnaire was passed to the pupils (see appendix: Motivation Test). This was extracted from Doctor R. C. Gadner’s test (2004). The questionnaire included twelve items, which had to be rated from one (low motivation) to seven (high motivation) by pupils from both classes. This test allowed to categorise them in three groups: high, medium and low initial motivation. At the end of the teaching period, some motivation questions were passed as part of the grammar post-test (see appendix: Grammar Post-test, question 5). It included six questions related to the work within the five groups, which were based on Ribé R. and Vidal L. (1995: 106). This test again allowed to categorise them in three groups: high, medium and low initial motivation, in order to permit the comparison of pre and post data. GRAMMAR COMPETENCE The first day a diagnostic test (see appendix: Diagnostic Test), based on the educational program of the school, was passed in order to identify students’ strengths and weaknesses and to prepare the subsequent project works. In this test only their grammar competence was evaluated. The test, prepared by me, was composed by five questions taken from the grammar units the less advanced students should have worked on during the first term. The exam included some activities following the “filling the gaps” type of exercise, which were taken from different pages of Naunton, J. (1997) and Betty’s Basic English Grammar edited by Prentice-Hall. These grammar units were: past simple (regular and irregular verbs), comparatives and superlatives, much and many, and conditionals (zero, first and second). At the end of the teaching period, a grammar post-test was passed. It had the same grammar contents as the one passed at the first session, but with elements from reading materials and worksheets, so that they were meaningful to them. (See appendix: Grammar Post-test). This final test ended thanking them their participation, since without their help it would have been impossible to have had a sample and thus, to test the hypothesis. 24 In order to have both valid and reliable results, the sample had the same environment conditions at the time of fulfilling it. The comparison of both motivation and grammar pre and post tests, as well as my personal views, permits to evaluate the results in order to asses the adequacy of the hypothesis initially described. 6. Analysis of the results This section presents and analyses the different results that have been obtained after my teaching practices period, and will help to asses the hypothesis stated at the beginning. Results come from the tests distributed among the students before and after the teaching period, as well as some personal assessments which were done during the teaching period. The analysis of the results will be mainly based in the comparison of this pre and post tests and will be related to the variables identified in the previous section: motivation and grammar. Results will be displayed in graphics, as it is considered a visual and easy way to show them. A corresponding explanation will follow each graphic in order to facilitate its fully comprehension. The main objective of this research work is to test the effect of collaborative learning by means of two project works in student’s English comprehension, trying to confirm as the review of literature states, that students could improve their English comprehension thanks to their work in groups. Motivation should increase and also grammar improvements could be shown thanks to the help that weaker students could take from their classmates. Beginning with one of the two variables related to this hypothesis, the following graphics are going to show the results that have been gathered from the pre and post tests on MOTIVATION, that were distributed among the two classes I worked with. It should be remained that Class I was formed by 24 pupils, and received both project works. On the other hand, Class II was composed by 25 pupils which only received project work 1. That was due to lack of interest in the second topic. Further information on this can be found at the previous section (methodology). 25 The first graphic below presents the results obtained from the sample in the pre-test on motivation. After fulfilling the motivation test, and according to their answers, pupils were classified in three categories: pupils with high, medium or low initial motivation. MOTIVATION PRE-TEST - Class I 4 low medium 14 6 high MOTIVATION PRE-TEST - Class II 7 17 low medium 11 high As it can be observed, the information above shows an initial situation with almost more than a half of each class motivated with English. Equally, the number of low motivated pupils was very small in both of them with less than ten pupils in this category in each class. The interesting aspect here is that Class II had a smaller number of highly motivated pupils with English, and it was the classroom where problems of lack of interest arose and which finally didn’t received the second project work. This lack of initial motivation could be one of the reasons why the second project work did not result interesting to them. In any case, the pre-project situation in both classes is very similar with almost more than the half of pupils with high motivation, being a little bit higher in Class I. In order to continue analysing and explaining the results on this first variable, the chart below represents results obtained in the post motivation tests which were passed to the same sample after working with them with the method during the teaching period. Again, it should be noted that the last day of my teaching practices, when the post test was passed to the pupils, not all of them attended the class. Therefore, a new category 26 has been added to present the same total number of results: 24 pupils for the first class and 25 for the second. This second category has been categorised as “no data”. MOTIVATION POST-TEST - Class I 1 5 0 low medium high no data 18 MOTIVATION POST-TEST - Class II 1 4 8 low medium high no data 12 This “no data” category responds to lack of information from some pupils. This lack of information comes from two different situations, the first one is from pupils who did not attended the last day class due to different reasons. This number is: 4 absent pupils in Class I and 3 absent pupils in Class II. The second situation related to the “no data” category includes: the absence of data from one pupil of Class I who didn’t answered any motivation questions, and five pupils of Class II who didn’t gave me back any final test. In order to compare the post-method situation with regard to motivation, the charts below represent the same data that the ones above but excluding the absent pupils. These second charts will allow us to understand the impact of results of the project method in motivation, in terms of percentages. In these graphs, lack of data from not answered test is (intentionally) classified as low motivated. The only excluded lack of data is the one from absent pupils. MOTIVATION POST-TEST - Class I excluding absent pupils 2 0 low medium high 18 27 MOTIVATION POST-TEST - Class II excluding absent pupils 6 low medium high 12 4 As it can be observed, the information above shows best results in motivation with Class I than Class II. That is the class which received both project works. Class I has lost the category of mid motivated pupils, and has only high and low motivated ones. Also, the percentage of high motivated is much higher that the low motivated, it surpasses the 75%. On the other hand, Class II has more than a half of high motivated pupils, and also a good representation of mid and low motivated ones. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the method in terms of MOTIVATION, it is included a visual summary of what has been obtained before and after the teaching period in both classes: MOTIVATION PRE-TEST - Class I MOTIVATION PRE-TEST - Class II 4 7 low 14 6 17 medium low high medium 11 MOTIVATION POST-TEST - Class I high MOTIVATION POST-TEST - Class II excluding absent pupils excluding absent pupils 2 0 low 6 medium low high medium high 12 18 4 The information above corroborates the positive results of the project method in terms of motivation. This information should be seen in terms of percentages and not number of 28 pupils in each category, as according to what was previously explained, there are some missed data due to the absence of some pupils in the last day of the teaching period. Seeing the considerable difference between both pre and post results in both classes, there is no doubt that motivation increased after the development of the teaching practices. It also can be noted that this increase was higher in Class I where both project works were developed. Therefore, taking into consideration this first result, it can be thought that the first part of the hypothesis (the one related to motivation) worked. Some of the reasons behind that success, which had helped to increase this motivation are: - Work with not confident students: when presenting the project two shy students did not feel confident enough to talk in front of the class. We agreed that one of them was the person in charge of saying where the singers were from and locating those cities on a map. The other one, a student from a different group who has a slight stutter, was helped and encouraged by the members of the group and finally presented the music style he was assigned to. Students listened to him in a respectful manner and he felt happy with the challenge. - Improvement of the environment conditions to reinforce pupils self confidence: in order to avoid noises and that some students get distracted, students were asked to answer a set of questions related to their classmates’ presentations during the second project. The result of this measure was highly positive. - Change in the class dynamic: the sole change in their teaching scheme also could be attractive to pupils and help to increase their motivation. A new teacher and exercises with music, groups... were different to their usual way of working and could also help in the increased motivation. In any case, it should be noted that this change in the teaching method was not always seen as positive by pupils. Some of them, especially the brightest ones, raised problems to work in this more flexible way and intended to leave the teaching method to continue improving and evolving in their personalised individual lessons. That situation required also lot of work from my side, trying to motivate them in the teaching method adopted. Finally, looking at the second variable, GRAMMAR COMPETENCE, the following graphics are going to show the results that have been gathered from the pre and post tests distributed among the two classes I worked with. 29 The same conditions apply to the sample than in the previous explanation, which are number of students in each class (24 in Class I and 25 in Class II) and the lack of data in the last day of the teaching period. With regard to this second situation, numbers change in Class I as the pupil who did not answered the motivation questions, answered the grammar ones. So in Class I only 4 “no data” pupils appear, and all of them correspond to absent pupils. In Class II, the situation does not vary and it remains with 3 absent pupils and 5 not returned tests. In order to continue analysing and explaining the results that have been obtained, the chart below shows results in grammar knowledge obtained after passing the diagnosis test the first day. The graphs show the number of correct answers in each of the exercises in the test. These exercises were 1. verb-tenses; 2. verb-tenses (II), 3. much & many and 4. comparatives & superlatives and 5. conditionals (zero, first & second). Remember to evaluate them with regard to the number of pupils in each class (24 in Class I and 25 in Class II). GRAMMAR PRE-TEST - Class I 10 16 exercise 1 15 exercise 2 exercise 3 exercise 4 exercise 5 20 17 GRAMMAR PRE-TEST - Class II 9 19 11 exercise 1 exercise 2 exercise 3 exercise 4 exercise 5 15 21 According to this analysis, in Class I 16 pupils out of 24 passed the exercise 1 (verb-tense exercise); 20 passed the exercise 2 about “there was and there were”; 17 passed the exercise 3 (much-and-many exercise), 15 passed the exercise 4 about the use of 30 comparatives and superlatives and only 10 out of 24 pupils passed the exercise 5 on first conditional. In Class II, 19 pupils out of 24 passed the exercise 1 (verb-tense exercise); 21 passed the exercise 2 about “there was and there were”; 15 passed the exercise 3 (much-and-many exercise), 11 passed the exercise 4 about the use of comparatives and superlatives and only 9 out of 24 pupils passed the exercise 5 on first conditional. In any case, the initial level from both classes was very similar, and the difficulty of the different types of exercises was also similar to both classes. As it can be seen, exercises 1 and 2 got the best success rates, and exercises 3, 4 and 5 were the ones with the lowest ones. These results were taken into consideration when designing the project works. This way, during the first project work, we worked on texts which talked about past events, and an activity on past simple was also designed. Moreover, as some students also had problems with comparatives and superlatives, a worksheet and a listening exercise were specially designed to solve this problem. Moreover, even advanced students had problems with some irregular comparisons (far, farther/further, farthest/furthest) and made mistakes about the use of “much” and “many”. Finally, most of the weaker students did not know how to form the first conditional. Because of that the fourth session was devoted to explain the use of “much”, “many”, “enough”, and zero, first and second conditional. After designing the specific grammar content of the project works to cope with this lack of knowledge, results were measured again with the grammar post test. As it has been fully explained at section 5 (methodology), the content was very similar to the pre-test (to allow the correct comparison of both pre and post tests) but with elements from reading materials and worksheets, so that they were meaningful to them. It should be noted that exercises 1 and 2 in the pre-test referred to verb-tenses and got positive results. This way, in the grammar post-test, they were melted in one exercise. This way, the exercises in the post grammar test were: 1. past tens; 2. comparatives & superlatives; 3. (zero, first & second). The charts below show the results: 31 GRAMMAR POST-TEST - Class I 4 8 19 excercise 1 excercise 2 excercise 3 excercise 4 16 no data 18 GRAMMAR POST-TEST - Class II 7 15 5 excercise 1 excercise 2 excercise 3 excercise 4 no data 16 17 As it can be observed, the information above shows a similar trend in the answers of both classes, in terms of percentages of success in each type of exercise. Again, the most complicated exercises for both groups were the “much”, “many”, “enough”, and zero, first and second conditional (exercises 3 and 4). In order to compare the pre and post-method situation with regard to grammar competence, the charts below represent the same data that the ones above but excluding the absent pupils (“no data” category). GRAMMAR POST-TEST - Class I excluding absent pupils 8 19 excercise 1 excercise 2 excercise 3 16 excercise 4 18 GRAMMAR POST-TEST - Class II excluding absent pupils 5 15 excercise 1 16 excercise 2 excercise 3 excercise 4 17 32 As it can be observed, the information above confirms a similar level in grammar competence in both classes percentages. Nevertheless if we compare the number of correct answers in each exercise, we can see a slight difference: exercise 1 got 19/24 correct answers in Class I compared to 15/25 correct answers in Class II. Exercise 2 got 18/24 and 17/25; exercise 3 16/24 and 16/25; and finally exercise 4 had 8 correct answers out of 24 pupils in Class I and 5 correct answers out of 25 pupils in Class II. The interesting aspect here is that the best results were obtained in Class I, the one that received both project works. These seem to be the central lacks of grammar knowledge that require further work, as exercises 3 and 4 still have the lowest success rates. Therefore, taking into consideration these results, it can be thought that the development of the project works had a positive influence in the grammar competence of the sample tested. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the method in terms of GRAMMAR COMPETENCE, it is included a visual summary of what has been obtained before and after the teaching period in both classes: GRAMMAR PRE-TEST - Class I 10 GRAMMAR PRE-TEST - Class II 16 9 exercise 1 15 19 11 exercise 1 exercise 2 exercise 2 exercise 3 exercise 3 exercise 4 exercise 4 exercise 5 exercise 5 20 15 17 GRAMMAR POST-TEST - Class I 21 GRAMMAR POST-TEST - Class II excluding absent pupils excluding absent pupils 8 5 19 15 excercise 1 excercise 2 excercise 1 16 excercise 2 excercise 3 16 excercise 3 excercise 4 18 excercise 4 17 The information above corroborates the positive results of the project method in terms of grammar competence. The information in percentages shows a static situation with regard to the complexity of the different types of exercises for the pupils. They still consider conditionals the most complicated type of exercise (with the lowest success rate). This is 33 normal, as conditionals are more advanced complex than the other exercises. In any case, an improvement in the positive scores of each exercise can be seen, which moreover, is more relevant in Class I, the one that received both project works. Seeing the difference between both pre and post results in both classes, and specially in Class I, it can be stated that grammar knowledge increased after the development of the teaching practices. It also can be noted that this increase was higher in Class I where both project works were developed. Therefore, taking into consideration this result, it can be thought that the second part of the hypothesis (the one related to grammar competence) also worked. Finally, this last graphic acts as a visual summary of what has been presented before, but, this time, all the information and the consequent comparisons can be appreciated in a single view. It represents the results obtained in terms of the two identified variables: motivation and grammar competence. Variable 1: Motivation. 34 Variable 2: Grammar competence. To conclude, if we remember the hypothesis “to test the positive effect of collaborative learning by means of two project works in student’s English comprehension” and the research questions related to it: 1. Does the project method and therefore collaborative learning increase students’ motivation in schools with a personalised learning system? Does this method increase their willing to learn and, therefore, the number of hours of learning devoted to this subject? 2. Do students who interact in project works get better results in grammar? We can confirm the positive answer to both research questions, and thus the effectiveness of the project method and the confirmation of the hypothesis. 35 7. Conclusions The main purpose of this research has been to investigate about the influence that a collaborative learning method could have on students English comprehension. This objective was defined after a first visit to the school I was assigned to work with during my teaching practices. The school had a very innovative teaching system, based on a methodology called Basic Interactive Education (EBI Spanish acronym) which encourages students’ autonomy. According to that teaching system, each pupil evolved through the course lessons in their own timelines and usually worked alone, with the unique support of the teacher and a computer, and with fewer opportunities to interact among his classmates. The hypothesis initially formulated tried to demonstrate that, despite the benefits that the pre-existing individualised and innovative teaching method could have, a more traditional teaching scheme developed at English classes, could end in positive impacts in terms of motivation and improvement of grammar knowledge. This new scheme, would enable the fulfilment of a common task among students who usually work at their own pace on different units. Students would work cooperatively in teams, and weaker students will take advantage learning from the brighter ones. They will also socialise more, and will enjoy learning English at the same time that they revise some grammar points which they have to improve. The intention of developing a team-based learning assignment was to ‘break out’ of the normal format and encourage ‘active’ learning, which was challenging, as it was promoting a new activity by confronting students with their colleagues in teams. The review of literature has mainly been focused on the positive effects that this type of learning could have. Many researchers also reflect in the same way, with several authors supporting this idea: Dewey, Kilpatrick, Charters and Bode (the classical authors who formulated the project-work method applied in this research,); Waks, L. J. (1997), Núria Vidal, who, according to Antonio R. Roldán Tapia (1997), acknowledged the importance of the communicative learning method, or Tom Hutchinson (2001). Apart from establishing the main hypothesis which was “to test the positive effect of collaborative learning by means of two project works in student’s English comprehension”, some research questions were raised to help in the development of that main idea. 36 Thanks to the investigation carried out, those questions as well as the main hypotheses have found their corresponding answers. In order to choose the right methodology for this particular research work, many aspects have been taken into account. Some of these important aspects are the participants (the sample), the materials and both the dependent and the independent variables. The sample was composed by two third year of E.S.O. classrooms of 24 and 25 students each one of them. Each class was divided in five groups formed by weak and stronger students in English, so that the weaker ones take advantage of their classmates. The goal was to produce well-balanced teams with complementary skills. Materials included pictures and posters, a cassette with compact disc player, a monolingual dictionary, two project works specifically designed for the groups, as well as three tests, used to evaluate the results of the teaching method applied. Students were tested in an individual way, although they also worked both in groups. The third aspect, the dependent and the independent variables, was crucial to determine the flow of the whole methodology, since they suppose the main pillars of the hypothesis. Two main independent variables were identified: motivation and grammar knowledge. Both of them would have a positive influence in students English comprehension, so that according to the hypothesis, the higher motivation and grammar knowledge they achieve, the better English comprehension they will have. According to the review of literature, two pre-test were given to students to test the initial level of grammar motivation and knowledge of both classes. The one of grammar also helped to identify deficiencies that they should improve by means of the project works. At the end of the teaching period, a grammar post-test was passed. It also included one activity related to motivation evaluation with several questions students had to fulfil. The participants who have taken part in this experiment had the same environment conditions at the time of fulfilling them, what ensures results’ adequacy. Difference between the results in the tests obtained before and after the instruction period would allow us to assess the adequacy of the hypothesis. According to what was expected to find, the results obtained demonstrated an improvement in both variables, motivation and grammar competences, after the development of the project method. Thus, it can be concluded that the hypothesis tested was adequate. 37 Based on the results, I would improve the project in some ways. First, I would involve students in the selection of the topics for the project works. This way, one of the problems which appeared with Class II (lack of interest) would have been overcome. It would be worthwhile in future studies to include a differentiated study of the results obtained from students with high and low grammar level, to provide a better understanding of how did they feel the project method in terms of motivation, as well as how effective had it been in terms of improvement of grammar competence. I also realized that the project design would require a more dynamic format with different activities in each project work. Moreover, other English competences could have been more deeply developed, such as writing. More experiments would also be needed in order to draw stronger conclusions. Because of the small sample size and time constraints results should be treated carefully. For example, the outcomes may have varied if the sample had been composed by different age’s students. There also seems to be a group of pupils at the school who find this way of working monotonous or useless as they did not gave back their final tests. This could be also investigated. Additional questions could be formulated in order to further explore the method, such as: what low and high ability students perceive as the benefits (if any) that can be gleaned from working together on a project? Furthermore, there are additional variables that affect group work and could have been investigated. These include: pupils mood, or the time to explain and make pupils confident with the project method. Other variables, such as peer predisposition to work alone or in groups and the content of the projects should have been taken into account. This way, the findings of this study can not be generalized to cover all secondary school students and classrooms. We have to be conscious of the fact that the data set was small and so the results are tentative. Nevertheless, this study offers a significant contribution to educators’ understanding of some of the variables which influence students English comprehension and means to improve them. Although there are other researches on this topic, it should be remarked that it was the first collaborative project that the students received in this school, so the method was innovative there. I would like to conclude by thanking the students who have contributed to this research as without their help it wouldn’t have been possible. 38 8. Bibliography Betty (--) Basic English Grammar. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Fried-Booth, D. L. (2002). Project Work. Ed. Alan Manley. Oxford: Oxford University Press Hutchinson, T. (2001). Introduction to Project Work. Oxford (England): Oxford University Press Gardner R. C. (2004) Attitude/Motivation Test Battery: International AMTB Research Project. The University of Western Ontario, Canada Naunton, J. (1997) Think first Certificate. London: Longman and Schrampfer Azar Official Journal of the European Union, (2006) Recommendation on key competences for lifelong learning L 394 Oxford Collocations. Dictionary for students of English (2002). Oxford University Press Recommendation 2006/962/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 Ribé, Ribé R. y Vidal, N. (1993). Project Work, Step by Step. Oxford: Heinemann Ribé R. and Vidal L. (1995). La enseñanza de la lengua extranjera en la educación secundaria Roldán Tapia, A. R. (1997) El trabajo por proyectos en el sistema educativo español: revisión y propuestas de realización. Encuentro. Revista de Investigación e Innovación en la clase de idioma, 9 Waks, L. J. (1997) The project method in postindustrial education. Curriculum Studies 29(4) 391- 4 References for materials of the Project Works ● Books: Ribé, R. y Vidal, N. (1993). Project Work, Step by Step. Oxford: Heinemann ● Songs: The Beatles, Hey Jude ● Maps: Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_USA_with_state_names.svg (03/17/2012) Britannica Online for Kids. http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/art-143139 (04/14/2012) ● Computer sources: TY - GEN T1 - popular music Y1 - 03/17/2012 39 SO - Britannica Online for Kids UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-9275996/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273950/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273951/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273952/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273953/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273954/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273955/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273956/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273957/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273958/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273959/popular-music UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-273960/popular-music ER - THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND TY - GEN T1 - Ireland Y1 - 04/14/2012 SO - Britannica Online for Kids UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-9275089/Ireland ER NORTHERN IRELAND TY - GEN T1 - Northern Ireland Y1 - 04/14/2012 SO - Britannica Online for Kids UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-9275088/Northern-Ireland ER SCOTLAND TY - GEN T1 - Scotland Y1 - 04/14/2012 SO - Britannica Online for Kids UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-224844/Scotland ER WALES 40 TY - GEN T1 - Wales Y1 - 04/14/2012 SO - Britannica Online for Kids UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-9277638/Wales ER ENGLAND TY - GEN T1 - England Y1 - 04/14/2012 SO - Britannica Online for Kids UR - http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-274308/England ER - ● Allen, Rachel. Irish beef stew. http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/recipes/irishbeefstew_73826.pdf (04/14/2012) ● Thomson, Worrall Anthony. Winter vegetable colcannon. http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/recipes/wintervegetablecolca_73661.pdf (04/14/2012) ● BBC Food. Haggis. http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/recipes/haggis_66072.pdf (04/14/2012) ● The Hairy Bikers. Welsch rarebit. http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/recipes/welsh_rarebit_05821.pdf (04/14/2012) ● Robinson, Mike. Roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/recipes/roastbeefandyorkshir_72053.pdf (04/14/2012) 41 9. Appendix This section includes some materials used with the students. More concretely, it includes an example of each of the tests from which the outcomes presented in this document have been extracted. The documents below are attached in the same order as they were passed to the students. 42 Pre-motivation Test 43 Pre-grammar Test 44 45 Post-Grammar Test (plus post-motivation test, fifth exercise) 46 47