The Story of the Canadian Payments Association, 1980-2002

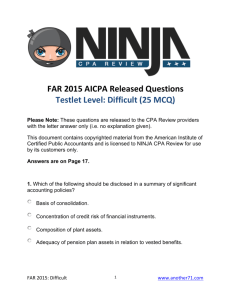

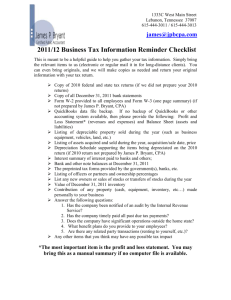

advertisement