PDF - Jindal School of Liberal Arts & Humanities

advertisement

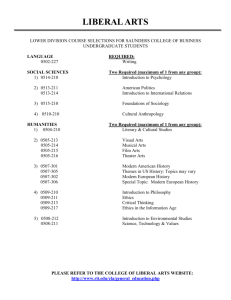

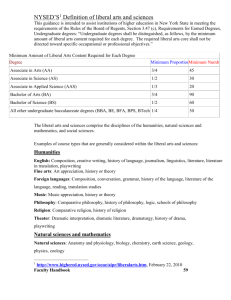

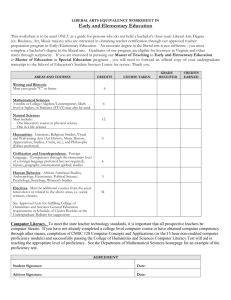

Jindal School of Liberal Arts & Humanities India's First Transnational Humanities School Vision Paper for the study of Liberal Arts and Humanities in India www.jslh.edu.in O.P. Jindal Global University (JGU) is a non-profit global university established by the Haryana Private Universities (Second Amendment) Act, 2009. JGU was established as a philanthropic initiative of Mr. Naveen Jindal, the Founding Chancellor in the memory of his father Mr. O.P. Jindal. The University Grants Commission has accorded its recognition to O.P. Jindal Global University. The vision of JGU is to promote global courses, global programmes, global curriculum, global research, global collaborations, and global interactions through global faculty. JGU is situated on a 80-acre state-of-the-art residential campus in the National Capital Region of Delhi. JGU is one of the few universities in Asia that maintain a 1:15 faculty-student ratio and appoint faculty members from different parts of the world with outstanding academic qualifications and experience. JGU has so far established five schools: Jindal Global Law School, Jindal Global Business School, Jindal School of International Affairs, Jindal School of Government and Public Policy and Jindal School of Liberal Arts & Humanities. www.jgu.edu.in In 2009, JGU established India's first global law school, namely, Jindal Global Law School (JGLS). JGLS is recognised by the Bar Council of India and offers a three-year LL.B. programme, five-year B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) and B.B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) programmes and a one-year LL.M. programme. JGLS has research interests in a variety of key policy areas, including: Global Corporate and Financial Law and Policy; Women, Law, and Social Change; Penology, Criminal Justice and Police Studies; Human Rights Studies; International Trade and Economic Laws; Global Governance and Policy; Health Law, Ethics, and Technology; Intellectual Property Rights Studies; Public Law and Jurisprudence; Environment and Climate Change Studies; South Asian Legal Studies; International Legal Studies; Psychology and Victimology Studies and Clinical Legal Programmes. JGLS has established international collaborations with law schools around the world, including Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Michigan, Cornell, UC Berkeley, UC Davis, Arizona, Oxford, Cambridge and Indiana. JGLS has also signed MoU with a number of reputed law firms in India and abroad, including White & Case, Amarchand & Mangaldas & Suresh A. Shroff & Co., AZB & Partners, FoxMandal Little, Luthra and Luthra Law offices, Khaitan & Co. and Nishith Desai Associates. www.jgbs.edu.in Jindal Global Business School (JGBS) offers an MBA programme and an integrated BBA-MBA programme. The vision of JGBS is to impart global business education to uniquely equip students, managers and professionals with the necessary knowledge, acumen and skills so that they can effectively tackle challenges faced by transnational business and industry. JGBS offers a multi-disciplinary global business education to foster academic excellence, industry partnerships and global collaborations. JGBS faculty is engaged in research on current issues including: Applied Finance, Business Policy, Decision Support Systems, Consumer Behavior, Globalization, Leadership and Change, Quantitative Methods, Information Systems, and Supply Chain & Logistics Management. JGBS has established international collaborations with several leading international schools including the Naveen Jindal School of Management, University of Texas at Dallas, USA, Kelley School of Business, Indiana, USA, European Business School, Germany and University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, Canada. Jindal School of International Affairs (JSIA) India's first Global Policy school is enhancing Indian and international capacities to analyse and solve world problems. It intends to strengthen India's intellectual base in international relations and affiliated social science disciplines that have hitherto been largely neglected by Indian academic institutions. JSIA offers a Master of Arts in Diplomacy, Law and Business [M.A. (DLB)]. The programme is the first of its kind in Asia, drawing upon the resources of global faculty in Jindal Global Law School, Jindal Global Business School, as well as the Jindal School of International Affairs to create a unique interdisciplinary pedagogy. The M.A. (DLB) is delivered on week days to residential students and on weekends for working professionals, including diplomats, based in the National Capital Region (NCR) of Delhi. JSIA has established international collaborations with the United Nations University in Tokyo and the School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) of Indiana University. JSIA hosts India's only Taiwan Education Centre, which has been established by National Tsing Hua University of Taiwan with the backing of the Ministry of Education, Government of Taiwan. JSIA publishes the Jindal Journal of International Affairs (JJIA), a critically acclaimed bi-annual academic journal featuring writings of Indian and international scholars and practitioners on contemporary world affairs. www.jsgp.edu.in www.jgls.edu.in www.jsia.edu.in Jindal School of Government and Public Policy (JSGP) offers India's first Master's Programme in Public Policy (MPP). MPP is interdisciplinary and draws upon multiple disciplines. It is designed to equip students with capacity to grasp contemporary economic, political and social challenges, coherently and comprehensively and to find solutions to persistent problems. Our public policy graduates have mastery over a range of tools and techniques essential for evidence-based policy-making. They are well-versed in monitoring and evaluation methods. They are trained to understand diverse contexts and complexity. They can design policies which are implementable and deliver desired results. They will be an asset to development and policy-related institutions, both within government and in civil society. Think-tanks, policy research institutions, consulting companies, corporate social responsibility initiatives, international organisations and the media must value the unique combination of skills, leadership, imagination, and ethics which JSGP graduates possess. JSGP has an outstanding faculty to equip its students to pursue successful and adventurous careers in many spheres of public life. JSGP has international collaborations befitting a global programme of high quality. JSGP is a member of a select group of public policy schools (including Harvard University, Sciences Po, Oxford University, Central European University, and many others) for participating in the Open Society Foundation's Rights and Governance Internship Programme. JSGP has a dedicated Placement and Career Development Cell which helps its graduates to pursue careers best suited to their skills and aptitude. The Jindal School of Liberal Arts & Humanities (JSLH) begins its first academic session in August 2014. It will offer an interdisciplinary under-graduate degree programme leading to the award of B.A. (Hons.). An education in the liberal arts and humanities programme at Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JSLH) in collaboration with Rollins College, Florida, is the ideal preparation for an intellect in action. JSLH offers a space for the expansion of young minds in a polyvalent education that mixes the classical and the contemporary in a new framework – the first of its kind in India. Our aim is to break down disciplinary boundaries and redefine what it means to study arts and humanities in an international context. At JSLH, our distinguished faculty aims to create world-class thinkers who are simultaneously innovators. We train students for intellectual mastery, democratic participation, selfexpression and advanced life-long learning. Our curriculum has been carefully crafted and has a global orientation. Within this global framework, the B.A. (Hons.) includes an exciting opportunity to solidify Jindal's liberal arts and humanities programme through an extended period of study at Rollins College, Florida, USA, leading to the award of another undergraduate degree from the USA. JSLH seeks to become one of the places that will produce the next generation of leaders to confront our overarching problems. Jindal School of Liberal Arts & Humanities India's First Transnational Humanities School www.jslh.edu.in Contents I. Twice Born Affair: Liberal Arts in Two Cultures ............................................. 2 A. A Framework for Diversity ...................................................................... 3 B. The Liberal Arts Ideal .............................................................................. 3 C. Four Perspectives from India .................................................................. 5 D. Four Revolutions of the 20th Century ..................................................... 8 E. A Vision for Leadership .......................................................................... 9 II. Why Liberal Arts? ....................................................................................... 12 A. Review of Liberal Arts Colleges ............................................................... 13 B. Comparison of some Liberal Arts Colleges .............................................. 13 C. Core-Elective Option ............................................................................. 14 D. Framework of Proposed Liberal Arts Course in India ............................. 14 III. Course Descriptions .................................................................................... 17 A. History and Historiography .................................................................... 17 B. Political Science ..................................................................................... 18 C. Sociology and Anthropology .................................................................. 18 D. Economics ............................................................................................. 19 E. English (Literature) .............................................................................. 20 F. Fine Arts ................................................................................................ 21 G. Interdisciplinary Seminar ...................................................................... 21 H. Performing Arts .................................................................................... 22 I. Psychology ............................................................................................ 23 J. Foreign Languages................................................................................. 23 IV. What kind of a person would a Jindal Liberal Arts Graduate Become? ......... 24 I A Twice Born Affair: Liberal Arts in Two Cultures Patrick Geddes, a Scottish biologist and first professor of sociology in India, often claimed that the university was an ecological system. The university has always responded to systems beyond, and subsystems within it. The Renaissance university as an ecological system grew as a response to the wandering Greeks. The Renaissance university then transformed itself by responding to the French Encyclopedists to become the modern Germanic university. The process of boundary maintenance and environmental response was also replicated within. Historians have documented how the American community college faced a challenge of survival from the large Germanic university. In responding to that challenge, the community college, with its largely puritan vision, became a Liberal Arts college, adapting the Oxford model of a degree-granting college to American conditions. The response to the challenge resulted in not just a model of survival and innovation, but also an institutionalization of diversity . Any experiment in creating a Liberal Arts college in India must be a twice-born affair. This is not because the effort is Brahminical or elitist but because the experiment has to be seen through two lenses. The American debates on the Liberal Arts from Lionel Trilling, Jacques Barzun, Martha Nussbaum to Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak are critical. The Indian debates centering around Rabindranath Tagore, Patrick Geddes, Radhakrishnan and D.S Kothari are equally crucial. These two perspectives can create a pluralistic view of Liberal Arts which is central to a 21st century global imagination. The United States is marked by the resilience of the Liberal Arts and their challenge to Ivy League dominance. India is now affected by new enthusiasm for the Liberal Arts and this has three different sources. The first is an incompleteness in humanities education in India. The second is the more recent readiness to pay for quality and meaning. The third is a sensitivity that realizes the importance of value frames, and the incompleteness of education and citizenship without an encounter with Liberal Arts and humanities. There is now a hunger for a Liberal Arts and humanities presence in India. The efforts of Mahindra and FLAME, Pune, are harbingers of a larger process. There is a tendency to evaluate Liberal Arts in terms of “commercial success”, for example, in terms of the number of people listed in the Forbes List of the most successful or powerful. One's vision has to be wider than that of generalist administrator and businessman. The very rituals of Liberal Arts summon the dissenter, the eccentric, the marginal and the custodian to maintain values which may not be mainstream. In terms of power, they may constitute departments of defeated knowledges, where the nurturing of memory becomes a new form of dissent. The story that comes to mind is Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. In a society where books are burnt, citizens become not only people of the book, but books themselves. Each dissenter memorizes a text as different as Hamlet, Sense and Sensibility and The Man without Qualities and becomes its trustee. 2 A. A Famework for Diversity An educationist planning a Liberal Arts and humanities system to complement the American model must recognize difference in order to find complementarities. The conversation of differences creates a globalism and pluralism. Indian entrants must encounter diversity of cultures and knowledges; must become aware that India has 50,000 varieties of rice and over a thousand varieties of mangoes. India's diversity gives it a cultural intensity of an everyday kind. The linguist Prabodh Pandit captured it in one of his lectures in these words: “Consider the language routines of a Gujarati businessman, a spice merchant, 50 years ago, and settled in Bombay. How many languages would he use in the course of the day and in what contexts? Our Gujarati businessman, who was more likely to have hailed from the Saurashtra coast, spoke his variety of Gujarati at home. He probably lived in Ghatkopar, a suburb of North Bombay. When he went out in the morning to buy vegetables, since the vegetable vendors spoke colloquial Marathi (spoken in the coastal district of Colaba), he spoke colloquial Marathi with them; he caught the 9:35 suburban train to the city. To buy his ticket or transact any business with the officers of the railway, who were more likely to be Anglo-Indians rather than speakers of Gujarati or Marathi, he spoke in colloquial Hindustani. As a spice merchant, his sphere of activity was in the spice market around Masjid Bunder; because the merchants in the spice trade were mainly speakers of Gujarati, Kacchi and Konkani, our merchant spent his business hours speaking and listening to these three languages. If he was educated in English, say up to matriculation, he might occasionally read an English newspaper; he might also see a Hindustani film with his family. The number of languages he used in a day's routine was about six; but note that he used them in limited and specific contexts only.” India is a multilingual and multi-civilizational society. Its very diversity creates a cultural and ethical responsibility. One of the primary responsibilities of a Liberal Arts and humanities course is to sustain that diversity ethically, culturally, and politically. In that sense, a regime of Liberal Arts and humanities must be both canonical, thus sustaining the mainstream versions, and yet be plural. A Liberal Arts and humanities consideration of the Ramayana is responsible for its 300 variants. An interpreter of culture has to resist any effort to eliminate other versions. In fact, in a developmental India, a Liberal Arts and humanities culture must become a custodian of defeated languages and defeated peoples. The ethics of Liberal Arts and humanities demand that the last tribal and the lost storyteller are sustained. A strict adherence to the canonical, the classic and the mainstream are inadequate and ill-fitting in India's cultural landscape. B. The Liberal Arts Ideal Who will be the Liberal Arts student of tomorrow? What does he or she need to be and to learn? What is the intellectual ecology of a Liberal Arts school today? How does the architectonic blend with the architecture? Should the Indian Liberal Arts school operate like most of the American equivalents in consortiums like the seven sisters, the little Ivies or the five college consortium? One thing is clear. Ours can be a collaborative exercise with institutions abroad. The Liberal Arts experiment is too new 3 to evoke resonances. Many Indian efforts are still nominal or rich as rumors waiting confirmation. A conversation with institutions like Shiv Nadar University, Mahindra College, FLAME, or Ashoka University, to be built next door, is on the cards. But for the present, affinities are more abroad. The deeper question is what is the nature of the social contract that we are affirming. The Liberal Arts and humanities college is a value frame or a particular ideal of education. It emphasizes the teacher as an exemplar. Performativity and commitment become important. A teacher becomes a legend who creates the folklore of Liberal Arts. The student is not a passive creature. She is a creator and inventor of a new self or a renewed self. She is a seeker, explorer and the syllabus becomes a map of possibilities. In a Deleuzian sense, inventing Liberal Arts is not about tracing. Mapping is an act of reinvention; one explores, invents and rediscovers a territory. Pedagogy becomes crucial because it is the act of teaching that is the eventual educational act, a drama unfolding everyday around a canonical text, an invitation to re-reading as an unfolding invention. There is also the dream of democracy. Liberal Arts and humanities provide the syllabus for a democratic way of life. It is here that cosmos, a community, a constitution and a syllabus can all integrate into a four-fold way of life we can call democratic. The ideas of a cosmos invokes world views anchored in religions and civilizations, creating an integrated relation between man, nature and god, providing a multiverse of meanings, where old dichotomies between politics and religion, science and religion are re-explored. A cosmos needs a community or a neighborhood of communities to embed it and embrace it. A community needs a history, a story teller and an ethics of memory which becomes the basis of an ethics of caring. Liberal Arts and humanities is fundamentally about responsibility, leadership and judgment, the creativity of standing up for something. Cosmos and community require a constitution, a value frame of laws to anchor it. A constitution is not only a founding document but one of the great texts demanding a ritual of interpretation. A community of Liberal Arts links these three domains into a syllabus. A syllabus is a promissory note, a vision document, a cognitive constitution for the academe. It is a dovetailing of these three ideas or entities that produces the world of a Liberal Arts and humanities college. Liberal Arts is about citizenship building, much more than consumerism or voter's choice. The citizen is a person of knowledge exploring the intricacies of choice and the nature of alternative imaginations. Ethics, aesthetics, politics become essential to the act of engagement. A perspective in Liberal Arts creates the humus for judgment. While emphasizing the life of a book, the college opens out to the book of life, creating the citizen scholar as the basis of democracy. It is in this context that citizenship, civility and civitas become lived ideals of a democratic society. Liberal Arts and humanities provide both the table manners and the customs and the frames of justice of a democratic society. The concept of Liberal Arts encompasses the public/private distinction. Liberal Arts cannot provide for a private aesthetics, or the individual choices of an 4 authoritarian society. It has to enter, frame and question the public domain. This act of interrogating the public domain calls for a pro-active notion of citizenship and leadership. The Liberal Arts programme in India must have a dual cognitive role. It must be a custodian of many canons but it should also be the caretaker of an intellectual commons. The word 'commons' usually referred to a space outside the village where everyone could access timber, food, medicines and obtain access to pasture land. But the commons was not only a material enclave of access; it was an imagination, a repository of skills and survival tactics. A commons is thus not only a material base but also a locus of knowledge, kept alive outside the formal economy. It is this idea of the commons that has been reinvented both by cyberspace netizens and by citizens fighting the intrusions of the new regimes of intellectual property. A Liberal Arts faculty as a new commons seeks to de-commoditize knowledge and treat it as the perpetual gift to be renewed by every generation and through every act of reading. Archives, libraries, studios, museums have to fall within the definition of the new intellectual commons. As an ethics of memory, Liberal Arts seeks to revive the marginal and sustain it. The difference between an intellectual commons and a museum is crucial. A museum preserves the dead and the defeated for posterity. A commons summons the present as a repertoire of skills that sustains the marginal and the threatened. This becomes clear in the debates on education during the national movement. The poet, Rabindranath Tagore, felt that a dialogue of civilizations would be a dialogue of the universities. His effort, along with that of Geddes, Gandhi and others was to build an Indian university which embodied such a civilizational imagination. Patrick Geddes, positing a post Germanic university, argued that a university grew by absorbing and debating with the dissenting academies around it. Geddes, Bose, Tagore were looking for a university as an evolving cosmopolitan imagination. Cosmopolitanism goes beyond ethnocentricity, the nation state or even internationalism. Cosmopolitanism does not see interdisciplinarity or multiculturalism as forms of trespassing. In this process, the Indian cultural imagination not only studied the dominant West in its canonicity, it read the other wests and sought to retain them within its germ pool of alternative possibilities. A regime of Liberal Arts cannot produce mimic men and women. The fundamental ritual is the act of questioning the basic myth. The critical mind, with its sense of the classic, has an ethics of memory, with its sense of hermeneutics it perpetually lives, relives and outlives a question. The question, the conversation, the debate and the seminar are not just pedagogical inventions, they mark and model ways of life. The civility of the debate, the community of the classic and the syllabus simulating a constitution of texts creates the everyday world of Liberal Arts and humanities. C. Four Perspectives from India A Liberal Arts and humanities programme has to realize that its legacy of debate gives it a particular perspective on: 5 1) The place of the oral in the narrative imagination. 2) The fate of crafts in an industrial society. 3) The constitution of anthropology in a post- colonial society. 4) Dialogue of religions in syncretic societies. Central to Liberal Arts is the theory of text. The question of how to read a text and the problem of translation are crucial to that central art we call hermeneutics. The problem of hermeneutics deals not just with how to read a book and to explore the pleasures of the text. A country like India must confront the power of the oral imagination in creating the narratives of the time. The official Indian definition of language as only that form of life that has a written script needs to be challenged in any theory of Liberal Arts. In such a newly constituted framework, the hypertext as a digital form, the oral narratives and the reading of the text becomes a triptych, a tripartite imagination for Liberal Arts as the new intellectual commons (Fig. 1) Oral Communication Life-worlds Textual Digital Fig. 1 The Western theory of Liberal Arts is based on the Renaissance distinctions between the art and craft. One must add that for the great art critic of the nationalist movement, Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, this distinction led to the decline of crafts and museumized them. It led to the museum smelling of death and formaldehyde. He questions the distinction as an intrinsic part of any humanities agenda, both on ethical and aesthetic grounds. An Indian theory of Liberal Arts must be sensitive to these issues and create a more life giving attitude to craft, not as a part of a dying tradition, but as an essential part of everydayness. Coomaraswamy challenged the distinction between arts and crafts. He argued that art is not a special kind of vocation but everyman in the pursuit of his art is a special kind of artist. A liberal theory of arts must move beyond the Coomaraswamy argument while emphasizing his view was not backward looking. Coomaraswamy coined the idea of the post-industrial society as a futuristic vision of craft society long before the sociologist Daniel Bell popularized the concept. Our idea of craft involves not just the coordination of mind and body. The body returns as a paradigm for various activities and is surrounded by the ecology of the sensorium. Between the body as praxis and education as the recovery and connectivity of sights, smells, touch, taste and sounds, the availability of a grounded pedagogy becomes more open-ended (Fig. 2). Liberal Arts as 6 Transformation of crafts Fig. 2 an ecology of sensitivity opens out to nature. The studio, the garden and the workshop become sites for the experimental creativity of the humanities. One would also like to playfully suggest that the body, craft and sensorium extend to music, drama and theatre. This experimental mode allows for new forms of perception, new ideas of experimentation and a translation which goes beyond text to the senses. One remembers the words of the great theatre director M.V. Subanna, the man who guided the Ninasam theatre in Heggudu, Karnataka, who claimed that drama does not sound true until it is enacted in at least two languages. Brecht's Galileo, he insisted, had a different resonance in Malayalam. One has to emphasize that the role of crafts is not just as a form of doing but as a mode of theorizing about creativity in a pedagogic way (Fig. 3). Pedagogic sites Fig. 3 India is a seat of major religions. The dialogue of religions has been an intrinsic part of our society. India is not just a Hindu society; it is the original site of Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism. In a deep sense, India is also an Islamic society. Demographically, it is, in fact, the second biggest Muslim nation after Indonesia. Christianity is older in India than in the West, having entered India in 51 AD. The dialogue of religions and the accompanying dialogue of medicines has been a part of our syncretic tradition. To comparative religion ,we can add the need for a comparative sociology. 7 After World War-II and the rise of the nation states, sociology and anthropology confronted each other. Anthropology was seen as the study of other cultures, generally of small scale societies. Anthropology was clearly the study of the other and other societies in particular. Sociology was the study of our own society. From the western view, sociology was the study of industrial societies. These hard and fast distinctions were questioned with the breakdown of colonialism. What would one call a tribal with a Ph.D. in sociology? Is he a sociologist or anthropologist or should he create a social anthropology as a truly comparative science, as M.N.Srinivas and others have argued. A cosmopolitan social science recognises no divisions between the two disciplines. The works of Robert Bellah, Mary Douglas, Clifford Geertz, J.P.S Uberoi, Ashis Nandy, Sudhir Kakkar become reflections of this new integrative science. Its syllabus must seek a synergy of both imaginations. Claude Levis Strauss's idea of anthropology in this wider sense emphasized the idea of a Pity. Pity, said Levi Strauss is empathy, the identification with the other, the affirmation that no self is complete without the other and that any society is incomplete in itself. Cross cultural understanding becomes central to comprehending humanity. Social anthropology by definition transcends the ethnocentric. D. Four Revolutions of the 20 Century As a country, we are clear that we are rich in debates that add to the legends of Liberal Arts. Yet we must also accept that India and the Indian university missed out on the four great revolutions of knowledge that took place in the West (Fig. 4). The transformational nature of each of these events was ignored or absorbed only by a fragment of our society. The Quantum revolution and its implications for science have not entered the popular consciousness and even part of our scientific establishment. The revolution in biology and the accompanying developments in ecology have not touched policy. Oddly, we have debates about regulations in biotechnology but little about how biology reworked the scientific literacy of the century. Any course in Liberal Arts need to internalize the axioms of these debates and work out the implications for popular culture and democracy. th Methodologies for Liberal Arts Fig. 4 8 The two other revolutions also failed to shape our consciousness. These were two transformations that could have deeply altered the concepts of knowledge and pedagogy in our society. The first was the linguistic revolution heralded by Chomsky, Roman Jakobson and Claude Lévi-Strauss. The second was the transformation in the way we thought about knowledge. The new reflexivity of knowledge created by Bachelard, Canguilhem, Bateson, and the Macy conference on cybernetics, have all eluded us. Learning about learning or Deutero – learning is a critical part of the new knowledge society and our universities have engaged only superficially with it. The crafting of a Liberal Arts programme around the debates and methodologies of knowledge adds to a new self-reflexivity. Indians are often tempted to transplant knowledge systems without recognizing their genealogies. This often leads to a bowdlerization of knowledge where we echo slogans without internalizing concepts or recognizing the logic and the demands of the institutions we seek to build. E. A Vision for Leadership For a Liberal Arts ideal, leadership is a polyvalent term built around a multiplicity of contexts. The passive notion of citizenship which accepts and consumes law, governance or culture has to interrogate it, invent it and renew it. Peter Drucker's distinction between managers and leaders becomes relevant here. A manager merely does things right by way of management. His is a preoccupation with form, procedure, ritual or even habit. A leader does the right things. A different drama of agency is summoned here. There is a role call for choice, initiative and judgment for action. The danger in India is that a Liberal Arts programme creates consumption of a culture without action or leadership. A democratic society needs leaders in every domain of action, leaders ready to lead a nation, an army, a department or even reform a municipal office. If science documents emphasize innovations, the Liberal Arts domain must be equally focused on leaders and leadership. It is a Liberal Arts College that becomes a school of leadership, where ethical dramas and political choices are played out to the exemplars of tomorrow. This transformative ideal is central to a vision of global societies today. A Liberal Arts programme is both a custodian of memory and a critic of invention. But leadership calls for a different kind of creativity, a more demanding sense of holism. Such a theory of leadership goes beyond the holism of an interdisciplinary and multi-cultural view to a global, planetary vision where the parts connect in a new and transformative way. One thinks of a Vaclav Havel, a Martin Luther King or a Gandhi providing a different vision, altering connections in an unexpected way. A leadership inspired by a Liberal Arts perspective does not seek Promethean transformations. It is modest and self-reflective and seeks new ways of enriching and transforming wholes. The new scenarios of peace, struggles for sustainability and the new vision of city building calls for leadership of a different kind. Such a holistic vision realizes that in a specialized world ,the whole might become less than the sum of the parts.There is geography of imagination to a Liberal Arts programme. Liberal Arts cannot be treated as a mechanical act, a transfer of culture at par with a transfer of technology model. Liberal Arts does not represent a microcosm of a Western or 9 an American way of life and thought. It is an experiment in global thinking, a dialogue of cultures as a search for a richer whole. One deals with the local at the level of the body, the oral imagination, the dialect, the folktale but moves up an ethic of scale to wider complexity. An Indian imagination necessarily becomes a South Asian imagination in an encounter with the West. Even the idea of the whole is manifold. The International, the Cosmopolitan, the Planetary, the Global and the Human meet to create overlapping visions of holism, of a totality, of systems complexity. Liberal Arts leadership becomes that act of connectivity which provides the notions of responsibility, agency and prudence the global needs today. The pilgrimage of the liberal school then moves across a range of thresholds. First is the recognition of the contemporaneity, simultaneously and plurality of the oral, textual and digital as communicative mediums. Secondly, one has to embed Liberal Arts in a craft imagination where body and the sensorium anchor the creative process. Thirdly, Liberal Arts in India have to engage both with the critique of colonialism and a dialogue of civilizations. Liberal Arts confront cultures in a range of encounters. The methodological revolutions of Liberal Arts create a heuristics of space between science and the humanities. Finally, one creates ecologies of classifications where the classical and the interdisciplinary are played out. These rites of passage elaborate the cognitive world of a Liberal Arts college. (Fig. 5) Global/Indian/ South Asia specific Classification of Knowledges Fig. 5 10 Fig. 6 In the next part, we examine the more practical aspects of establishing a Liberal Arts and humanities College. 11 II Why Liberal Arts? The JSLH aspires to become a valuable addition to the family of existing Liberal Arts institutions across the world. It is a daunting task. From Pomona College in the Western United States to the incipient Yale-NUS Liberal Arts school in the East Asian metropolis of Singapore, Liberal Arts colleges have earned an enviable reputation for producing well-rounded graduates. This reputation rests on a commitment to inter-disciplinarity, development of critical thinking skills and proficiency in oral and written communication. These skills do not feature prominently in the current scheme of higher education in India. At present, Indian colleges emphasize accumulation of discipline-specific skills in a vacuum, i.e., without reference to the relationship between disciplines. Even though, some Indian colleges pay lip service to the merits of an inter-disciplinary education, they do not emphasize its incorporation in practice. Indeed, the strait-jacketed model of most Indian undergraduate institutions deters students from discovering connections between different disciplines. But artificial compartmentalization that fails to recognize the complexity of the interwoven problems afflicting humanity disables the imagination from conceiving of the multi-pronged and nuanced approaches needed to resolve them. The mission of JSLH is to establish a beachhead for interdisciplinary learning in India that will produce successful professionals who will lead society out of the morass it currently finds itself in. In an era of rapidly expanding globalization and heightened interaction between peoples and cultures, it is time to outgrow this parochial attitude toward learning. At the same time, the need for innovative thinking goes beyond its sanguine effect on students' employment prospects. For the first time, our planet faces ecological and military crises that endanger all of humanity. The solutions to such overarching problems will have to go beyond the limited country-specific or region-specific varieties that have been formulated in the past. In short, we need a new breed of leaders and JSLH seeks to become one of the places that will produce this next generation of leaders to confront these overarching problems. The next generation of leaders will need to break the shackles that confine our thinking into Manichean binaries and instead establish bonds of solidarity with those who possess a different understanding of the dilemmas that confront us. Hope for the future rests on a proliferation of such empathy. It requires going beyond demonstration of tolerance and civility that some other educational institutions proclaim as objectives of their educational programme. JSLH will seek to bring to life the underlying commonality which lies buried beneath the illusion of intractable differences. What is needed and what JSLH will promote are the spirit of enquiry, introspection, and critical engagement with the world at large. 12 A. Review of Liberal Arts Colleges Liberal Arts education is relatively new to India. It is important to recognize that the term “Liberal Arts college” may refer to one of two types of educational institutions in the United States. There are about 230 stand-alone Liberal Arts colleges which focus on undergraduate education and are characterized by small size and relatively low student -teacher ratios. Examples of such colleges are Middlebury College, Swarthmore College and Williams College. There are also Liberal Arts and science colleges embedded in larger multi-disciplinary universities. These are typically larger than the earlier-mentioned variant of Liberal Arts colleges and do not lay the same degree of emphasis on classroom interaction and teaching. A key component of U.S. Liberal Arts programme is the first-year seminar. This element of the curriculum holds a particular relevance for us at JGU because it is the means by which the foundational concepts of critical thinking and analysis are imparted to entering students. Students are introduced to the possibilities and benefits of interdisciplinary learning by investigating in-depth a particular issue or topic from different angles. Students and their professors will engage in very detailed reading of selected texts so as to grasp key techniques of reading and textual analysis. Because of the importance of these foundational concepts, class enrolment is capped at a certain number. This is to enable extensive interaction between faculty member and students and among students. Another key component of U.S. Liberal Arts programme is the system of pre- requisites or distribution requirements. This refers to a set of courses covering a broad range of subject areas [literature, philosophy, life sciences etc.] that every student must complete, irrespective of major, in order to graduate. A third key component of U.S. Liberal Arts programme is a first-year writing or composition course. Given the importance of writing as a means of assessment in Liberal Arts colleges, it is crucial that students be given an introduction to the art of writing. It is significant that U.S. students who are exposed to writing-based assessments for high school are nonetheless required to complete an introductory college-level writing course. These key components of U.S. Liberal Arts programme are very instructive. They tell us that the most important qualities or attributes that our students will have to possess are critical thinking and writing skills. B. Comparison of some Liberal Arts Colleges In preparation for designing a curriculum, the committee members looked at the current practices of several Liberal Arts colleges, both established and emerging endeavours from around the world. The colleges included Rollins College, Columbia College, Amherst College (from the United States), Oxford PPE and University of Tilburg (from Europe), Campion College (Australia) and the Yale- NUS programme. The programmes from India – FLAME, Pune and the proposed 13 programme by Delhi University were considered. These latter programmes are closer to traditional Indian degrees and do not capture the spirit of Liberal Arts colleges. C. Core-Elective Option All of the Liberal Arts colleges referred here follow a Core-Elective pattern of course offerings. The core course typically focuses on politics, economics, philosophy, literature, sociology, general science and scientific enquiry, and contemporary issues. Along with the core course, there is a strong emphasis on grammar and writing.In addition to the core course requirements, all the course offerings require 1/3rd of the curriculum to be centred on the major/concentration that the student chooses. Some colleges offer the option of a minor (which will not be the case at JGU, but an option for the student while at partnered universities). Considering the established pattern of a Core-Elective course outline, JGU will seek to establish the same. A specific feature of the above plan in a few colleges is the inter-disciplinary seminar which spans across disciplines and is usually offered by two or more faculty. All of the above colleges look at education as a process and not a form of production, which is typical of the formal education system in India. The Jindal School will build on a core-elective system. Core and Electives acquire a four-fold variety. The rituals of the Liberal Arts course can be visualized as a four-tiered layer of initiations. The first option which all students engage with is a set of meta-theoretical courses which create a reflexivity about knowledge. These include courses on the History of the Body, Ecology, Scale and Complexity, the Sensorium, Language and Translation, Future Studies, Philosophy of Science. These courses provide connectivity across disciplines and set the stage for classic introductions to a particular Liberal Arts subject. Supplementary meta- theory and classics offer inter-disciplinarity alongside courses on comparative religion, ecological economics and philosophies of technology. These add to the core competence of classics, the probing inventiveness of inter-disciplinarity. Finally, one has a series of courses which focus on the body, the sensorium, on the ideas of craft and community service. The notion of community service goes beyond social work. One idea the proposed Liberal Arts College is entertaining is a Gazetteer of Haryana state covering customs, ecology, language, governance. The Gazetteer began as an instrument of colonial governance but today it can serve as a voice of cultural pluralism and a creative identity kit for people. D. Framework of Proposed Liberal Arts Course in India Certain common features run through the proposed framework for courses. They are: (i) development of critical thinking skills; (ii) development of reflective thinking skills; (iii) small class size and faculty mentorship of students, and (iv) division of curriculum into core and elective courses supplemented by discovery courses and a craft imagination. A second significant commonality concerns reflective thinking. Reflective thinking is the ability to 14 constantly revisit one's own positions and lived experiences in the context of larger questions. Enrolment for the first-year interdisciplinary seminar and the first-year writing course should be capped at a certain number of students. These courses will form the backbone of the Liberal Arts experience and it is important that students get the most out of them. These courses can therefore be divided into more sections than the other courses in the Liberal Arts curriculum. JSLH will endeavour to incorporate the aforementioned trademark features of Liberal Arts learning in an Indian setting. It will do so by incorporating a core-elective format for the two-year duration of the JSLH programme. Students will spend their first-year learning fundamental techniques and methodologies of essential academic disciplines. These are: history, political science, English literature, sociology, philosophy, psychology, English writing and crafts and fine arts. When students enter their second year, they would be able to opt for elective courses. These will take on two forms – electives in students' area of academic concentration and electives closely related to or divergent from the students' core areas of academic concentration. Concentration courses will enable students to develop some degree of specialization in their preferred field; such specialization would facilitate a smooth transition to adopting a major discipline at a twinned College. The electives outside students' area of preference are equally important to the overall development of the key faculties associated with the Liberal Arts. These are central to developing the multidisciplinary approach to understanding the world and the diversity of its varied cultures. In addition to the above described courses, an integral component of the Liberal Arts programme will be an emphasis on writing. The importance of writing to a Liberal Arts curriculum and indeed to success in the professional world cannot beoverstated. JSLH will be geared toward inculcating students with the building blocks of effective written communication, including how to establish a thesis, how to defend and support that thesis in well-organized and connected paragraphs and how to connect one's argument to the larger academic conversation taking place about the relevant subject. (Table 1) 15 16 Political Economy of Budgeting Law and Sociology Sociology of Science Research MethodsQualitative/ Quantitative Social Stratification Civil Society and Social Movements Political Sociology of Violence Governance and Corruption Anthropology of Religion The Social Construction of the Constituent Assembly The Indian Constitution International Relations; Political History of the Cold War Ideology and Ideologists Indian Political ThoughtGandhi, Tagore, JP, Lohia and Ambedkar Introduction to Psephology The Politics of Nature Semiotics Hunger, Poverty and Development Introduction to Sociology of Religion Reading the Arthshastra Models and Data bases Ecological Economics Global Economy and International Trade Rational choice Development Economics Economics of Planning Micro-economics Macro-economics Classical Sociological Theory ( Marx, Weber, Durkheim, Simmel) Introduction to Political Theory Economics Sociology and Anthropology Politics Doing Hermeneutics Sociology of Literature Introduction to South Asian Literature Understanding Poetry Subalterns and Subaltern-ism/ Introduction to Postmodernism Comparative Literature The Problematics of Translation HermeneuticsHow to Read Texts Introduction to the Canon- Western Literature- Great Texts Literature Table 1 On Memory and Forgetting History of Science The Making of Nehruvian India Themes in Constitutional History Reading Colonialism Nationalism and the Nation-State History of the Body / Environmental History of India History and Historiography History Introduction to Ethics Environmental Philosophy Introduction to Gandhian Thought Language and Philosophy Analytical Philosophy/ Logic and Reasoning Introduction to Marxism Philosophy of Religion Western Philosophy Introduction to Indian Philosophy Philosophy Ethno Psychology Psychology of Violence Cognitive Psychology Social Psychology Freudian India Approaches to Psychology Psychology Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghattak Introduction to Bollywood Introduction to Cinema History of Sound Classical Indian or Western Music Folk Traditions in Music- Studies in Ethnomusicology History of Colour Craft and Craft Communities Introduction to Design Modernity, Modernism and Art Introduction to Theatre Fine Arts / Performing Arts Making of the Gazetteer Interdisciplinary seminar on Jewish, Christian and Hindu traditions Deconstructing Development Reports Oral History Workshop Policy Workshop Museums and Exhibitions Writing Workshop Investigating Political Events- a Course in Political Journalism Parliamentary Internship Theatre Workshop Others III Course Descriptions A. History and Historiography The fate of history and historical studies has led to quixotic endings and surprise recoveries. Chandra Babu Naidu, the former chief minister of Andhra Pradesh wished to close down departments of history or turn them into addendums of tourism departments. In another context, History exploded as a problem of identity and controversy around the debate over textbooks where left and right flexed their ideological muscles alternatively. The debates around Marxist, Liberal, and the Nationalist Historiography created a variety of cultic styles, each presenting a fascinating but fragmented reading of history. Another fascinating implication one needs to explore is the strange contemporaneity of ancient and medieval history. The presence of larger than life scholars like mathematician-numismatist DD Kosambi and of Romila Thapar, the impact of the Aligarh group of historians who produced remarkable studies of Muslim/Mughal period under the leadership of Irfan Habib deserves attention. Controversy, methods and ideologies have made history an evanescent subject. The debates around the lost river like Saraswati, the controversies around Babri Masjid have turned history into a profound policy minefield. The presence of the Subaltern Studies has become a major archive of historical studies. The emergence of oral history workshop, environmental history, history of science, technology and medicine has created fascinating sub-field which have become major sites for inter-disciplinary innovation. At an immediate level, the courses in History should introduce students to the (1) basic methods of the discipline, (2) locate the development of the discipline in the Indian context and (3) provide foundational understanding and critical faculties about Indian history as well as selected fragments of world history. The courses will therefore pay attention to chronological narrative spanning the ancient to the contemporary period and will also address specific thematic issues. The course will be attentive to the different vantage points that generate different forms of historical interpretation so as to provide students with the capacity to make mature judgements about the debates around equity and diversity that have marked the debates about the discipline in contemporary India. The core courses – Debates in Indian History and Historiography and Nationalism and the Nation State seek to provide the above understanding. Depending on availability of faculty, there will also be an attempt to deal with a wide variety of thematic courses which can be pursued by the student as part of their concentration. These courses can prepare them for careers in more intensive academic study in history, heritage studies, public administration, law, development, etc. A list of the electives that can be offered include-- Basis of Nation-Building in the Colonial Period; Nehru, Gandhi and Ambedkar; Themes in Indian Constitutional History, 1775-1947; Ancient Societies; Medieval and Early Modern World; Early India: Economy, Polity and Society; Reading Colonialism; Themes on Constitutional History; History of Science and Environmental History. 17 B. Political Science Political Science in India went through a variety of pedagogic and research phases. There were efforts to create political science as a textbook discourse rather than confronting it as texts as evidenced in the repeated use of Garner, Laski or Eddy Asirvatham's monographs. The text book phase opened out a plural domain. There was first the behavioural phase inspired by Americans like Karl Deutsch and Robert Dahl. The impact of Laswell was channelized through Satish Arora and others at CSDS. The second strand inspired a wave of empirical work centering around Election studies and Democracy triggered by Myron Weiner, Rajni Kothari, Bashiruddin Ahmed at CSDS, Delhi. This wave of work culminated in Kothari's classic study Politics in India which has been staple stuff for over three decades. Kothari's own effort to disown the book has had little impact on its popularity. The third wave was triggered by the Emergency and the re-reading of the Nehruvian tradition. This led to the masterful studies of civil society, social movements, the emergence of Human Rights, a political critique of development and a search for Alternatives. Academic politics also went activist with scholars writing for newspapers, establishing PUCL and PUDR. The civil society concern also went global in search for dissenting imaginations which led to establishment of Journals like Alternatives, Lokayan Bulletin, Futures which provided links to the dissenting imaginations in Eastern Europe. Liberalization caught social movements flat-footed creating a return to the political economy, structural reforms and an obsession with studies of governance. The shift to governance and public policy created a spate of think tanks and major policy institutes like Centre for Policy Research and the Observer Research Foundation. The diasporic obsession with efficiency created an emphasis on governance studies. The last wave of political issues in politics is the preoccupation with globalization and its consequences. We have outlined these experiments to emphasize the pluralism of political science and the varieties of political experience available to a young scholar. A Liberal Arts course on political science should be open to the varieties of exemplars and paradigms in political science. The centrality of democratic imagination in each of these variants must be emphasized. An entrant to political science could take a combination of choices within the following courses: Political Theory, The Indian State, Introduction to Civil Society and Social Movements; Comparative Judicial Processes; Nationalism, Colonialism and Post-colonial Theory; Reading the Arthashastra; Gender, Sexuality and Politics; Introduction to Psephology; Justice and Human Rights; Science, Technology and the Politics of the Environment; Urbanization and Urban Politics; Introduction to Developmental Processes; War and State Formation; Global Governance; Politics, Literature and Film; Governance and Corruption; and Political Sociology. C. Sociology and Anthropology Sociology and Anthropology are mediated by two styles. The Americans generally emphasize Cultural Anthropology and the British created a tradition of social anthropology. Cultural anthropology was more normative in its concerns as it dealt with societies which had declined or 18 ceased to exist and Social anthropology was a more functional and empirical as it dealt with actual societies. Indian social anthropology has to combine both traditions. Social anthropology in India includes tribe, village and city in simultaneity without seeing them as a development sequence. This social anthropological style was embodied best in Delhi School of Economics. M.N Srinivas and Andre Beteille set the tone linking expertise on tribal society, theorizing about caste and class and creating a huge ethnography of development around Contributions to Indian Sociology, Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), Sociological Bulletin. These journals have created a tremendous file of debates around issues like “a sociology of India”, “the mode of production debate”, “the modernity of traditions”. Classical anthropology approaches soon evolved into outstanding studies on violence, corruption, semiotics, ethnographies of poverty, imagination of the cities. One hopes to combine the colonial, the classic and cutting edge to create a more fascinating palette of choices. Both core Sociology courses and electives will try to develop the students' ability to understand the dynamic relationship between self and society, that is between individual agency and social structure; to comprehend how society has been produced historically, is constantly reproduced and how it changes; to understand the layers of identity and their formation through community, caste, class, gender, religion, region and nation and gauge how power and inequality operate through them. Using these theories, methodologies, categories and tools of enquiry, students should be able to develop critical thinking and analytical skills. These should help them to evaluate and develop evidence based arguments which question stereotypes and common sense assumptions about society; to identify how cultural, economic, historical, and institutional factors affect individual/community experience and how these local and global influences change identities and social formations giving rise to social movements. In keeping with our constitution the emphasis will be on inculcating values of social democracy, plurality and cultural diversity so that students can use the knowledge gained to bringing about real world change. To achieve the above objectives, there will be a set of core and elective courses designed so that student who leave JGU for a partnership college after two years receive an adequate foundation. The introductory course will be such that students from all streams are able to get an idea of the subject irrespective of whether they opt to do a concentration in that subject, and the remaining courses in sociology will remain open to other students as it is our endeavour that students should take a minimum number of courses outside their concentration. D. Economics Economics as a discipline is more variegated than usually understood. The student will begin by taking courses in macro- and micro economics and international trade. But beyond this the range of choices will vary across Rational Choice Theory, History of Economics Theory, Institutional Economics, Anthropology and Economics and Ecological Economics. The courses will attempt to create several levels of literacy. First, an ability to understand stocks and shares and read The 19 Economic Times and The Wall Street Journal. At a second level, the student must have a sevenleague boots grasp of the History of Economic theory, especially of political economy, institutional economics and ecological economics. A grasp of econometrics and rational choice is critical. The economic courses will seek both literacy and competence. The student should have the ability to interpret survey and census data, read a policy document. In the more particular context of India, he will have to understand the debates around the green revolution. One hopes this combination of special subjects, inter-disciplinary efforts and a special understanding of policy give a distinctive edge to the course. The aim of economics will be to develop a core understanding of the central tenets of the discipline: microeconomics and macroeconomics. These core courses will complement the subjects offered in other disciplines and will share similar concerns like institutional issues, dynamics of contemporary markets, along with the theories, methodologies, categories and tools of enquiry that are central to economics. These core courses will be complemented by electives like Quantitative Methods; Global Financial Architecture; Fiscal Policy and Planning, which will provide the necessary depth in understanding specific issues. The courses offered in the business school will also be open for the students to choose as an elective. E. English (Literature) George Steiner in his Language and Silence, claimed that a critic confronting a literary classic like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, or Proust sees the eunuch's shadow. Literary criticism earlier acknowledged its secondariness to the literary classics. Of late what one confronts is the creativity and originality of literary criticism. One cites Mikhail Bakhtin, Roland Barthes, Octavio Paz, Roman Jakobson, Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, George Lukacs among a galaxy of others. This breakthrough of criticism appeared as a result of the Structuralist, Formalist, Marxist and psychoanalytical methodologies which together provided a new way of reading the literary oeuvre. The second breakthrough in the literary imagination was the critique of canonical thought, the critique of mainstream syllabus by marginal and subaltern imagination demanding a plurality of canons. Thirdly, the inventions in psychology, cultural studies, feminist studies added new perspectives. The debates in transnational theory also lead to a new reciprocity where texts were not just translated from English but between subaltern languages. A student must have a basic mastery of hermeneutics, literary theory, structuralism, deconstruction as methodologies and perspectives. S/he must understand the interfaces between the oral, textual and the digital. The students must have a sense of drama and film. One recommends courses around Fo, Grotowski, Brecht, traditional folk forms like Jatra and Yakshagana. Music and drama must become two basic variants of the cultural craft. 20 The teaching in literature will be closely aligned with the grammar and writing courses. Keeping this in mind, the core courses in Literature will be South Asian Literature and Western Literature. These courses will give the students an idea of the literature produced in different areas of the world. This multiplicity goes well with the notion of Liberal Arts/humanities. The electives can be chosen from the following offerings - English Literature of the 19th Century; 20th Century Indian Writing; English Literature from Chaucer to Shakespeare; Classical Literature; Forms of Popular Fiction; Contemporary Literature; Literary Theory; Politics, Literature and Film. F. Fine Arts A component of Fine Arts is placed in the curriculum of Liberal Arts Degree Programme as it serves the core function to tap and trigger the cognitive faculty of human imagination and emotions as a reference point to understand the world encompassing us. The aim of this component is to enhance the faculty of critical thinking of the learners by their exposure to, and analysis of cultural artifacts and various modes of representations both visual as well as in print form in popular culture and otherwise. The curriculum on fine arts would be constitutive of studying various forms of artisticrepresentations in history and contemporary times such as Theatre, Film, Music, Paintings, Poetry, and Photography etc. The course would diagnose the emerging social trends of politics of aesthetics and the intersection of the role of market and the role of art in society and community. The course in fine arts is meant to contextualize the role of art in social interactions, social movements and resistance. Thus, it seeks to evolve learning which is sensitive to the various modes of social representations and cultural artifacts for effective participation in democratic governance. Apart from the above aspects, course offerings based on philosophy of music, paintings and photography will explore the role of music in social movements, bhakti movements and the evolution of culture. An emphasis will be placed on exploring the significance of expression in various forms in cultivating sympathetic imagination. Secondly, students would be introduced to the lives, works and vision of painters like Van Gogh, Picasso, Duchamp, Abanindranath Tagore, M.F. Hussain and Bhupen Kakkar. G. Interdisciplinary Seminar The Interdisciplinary Seminar, a core ritual, will expose first year students to the broad range of disciplines within a Liberal Arts education. The syllabus for this year-long course will contain readings that touch upon the arts, the humanities, and the social sciences. Because the Interdisciplinary Seminar will focus on a specific theme for an entire year, students will be able to see how a common subject of inquiry can be approached and understood from different disciplinary perspectives; rather than reifying disciplinary boundaries, in other words, this course will seek to problematize and challenge them. The lens and the kaleidoscope combine as perspectives here. The Interdisciplinary Seminar seeks to expose students to some of life's “great questions” – war and peace, injustice, the environment, human rights, culture, liberty – to help them progress toward that which WEB Du Bois described in The Souls of Black Folk as the singular goal of university education, “not to earn meat, but to know the end and aim of that life which meat nourishes.” 21 While this course will involve written work, the Interdisciplinary Seminar is particularly concerned to develop students' oral communication skills and active and engaged learning. This will be done through formal presentations during class and the presentation of a piece of original research based on the course's common theme at the annual Jindal School of Liberal Arts Research Colloquium each spring. Class sizes will be kept to no more than a dozen students in each seminar to facilitate the development of oral communication skills and to ensure that students actively engage in classroom discussions. Readings for the Interdisciplinary Seminar will be chosen from all of the disciplines in the School and will be presented in the syllabus in a structured manner. In addition to regular meetings of the course on campus, each year's cohort of students will take a field trip each trimester to a location, in Delhi or elsewhere, that will enhance learning of the course's chosen theme of study. The field trips will also lend a practical dimension to the theoretical discussions in the classroom and facilitate reflective learning and critical thinking. H. Performing Arts Liberal Arts and the education of the free mind has always been inspired by the performing and fine arts – music, art, theatre, dance. Any institution that offers degree programmes in the Liberal Arts would do well, therefore, to incorporate within its curriculum a selection of offerings from within the fine arts repertoire. There are some easily identifiable reasons why a focus on the performing arts portion of the curriculum may be important. Firstly, the strategic importance of the first part of the programme in India is a key to realizing the unique positional advantage the school enjoys in this regard. Indian culture is replete with some of the richest resources for the fine arts, and while most of the major universities in the country offer excellent courses in Liberal Arts and there exist separately specialized institutions for the fine arts, a marriage between the fields has not been undertaken as a serious exercise in any University. Secondly, the performing arts are a group of subjects that, in the current pedagogical setting of higher education in India, tend to be side-lined or sacrificed at the cost of degree programmes that are unable to incorporate courses on fine arts. Incoming students at the Liberal Arts school will be fresh from high school and it is in this age group that a love of theatre, dance, art and music often finds the first flashes of expression – it is important to recognize this and to be able to feed it. Thirdly, exposure to classical material in performing arts, taught in a classroom and workshop setting, is likely to significantly enhance a student's productivity of thought and expression, and direct talent in these arts. The inclusion of ancient texts and an opportunity to engage with practitioners and academics that represent the contemporary state of the art in India would place these students at a competitive advantage in seeking further education in these fields. Finally, it may be emphasized that a serious academic interest in the performing arts is yet to be developed in the academic culture of India and the establishment of this new school, with a pronounced presence of a performing arts faculty and students would assist in changing this and reinvigorating local and regional traditions and classical art forms in conjunction with bringing the global experience of the arts to the school, thus creating a sustaining symbiosis. 22 I. Psychology Psychology has stood in a liminal position between science and humanities. The behaviorist in a search of the archetypal rat has been a positivist like Skinner. Human sciences under Jung, Hillman and Laing have pushed psychology towards being a more humanistic effort. In India, most university departments and institutes have felt the urge towards scientism. But the Liberal Arts genealogy of psychology goes back to one of the first interpreters of Freud in India, Girindhar Sekhar Bose. The line from Bose to Nandy and Kakkar highlighted both the Frankfurt school and Ericksonian psychology. Psychology today serves many masters. A big portion of recruitment is by the army. HR specialists and consumer researchers have occupied huge chunks of the subject. But the humanistic impetus has always survived in the writings on violence, family, incest and urban anomic. Riots and disasters have provided the ethnographic humus for such efforts. The student exploring the field should grasp the liminal nature of the discipline. Core courses could center around the history of psychology from Charcot, Breuer, Mesmer, Pavlov, Luria, Freud down to the behaviorists. A second core could be around Freud in India. One could think of a spate of electives around social psychology, cognitive psychology, ethno psychology and organization psychology. As an elective subject, it will begin at the margins. But one hopes it will grow gradually at Jindal. J. Foreign Languages Knowing a foreign language is often key to mastering certain social sciences and grasping the full meaning of philosophical and technical terms. It fosters complex and dynamic sensitivity towards the culture/cultures where the language is in use as culture and language are often mutually constitutive. Being able to interact in a foreign language opens doors to global careers and deep, meaningful interactions. More, translation as a rite of passage between languages adds to the dialogue of self and other. The process of learning to write a foreign language will also sharpen writing skills and thought process and also have a positive impact on the usage of English and other languages. It is equally important to learn languages at an earlier stage to enhance the aptitude and inclination to these languages. The following languages are recommended based on geographical coverage and relevance to social sciences and world affairs – Arabic, Mandarin, German, French, and Spanish. Considering the fact that foreign languages will not be a part of the core curriculum, it is suggested that language training should be in addition to the requirements to earn a degree. A 1 full credit course should be compulsory for all students and this should result in intermediate-advanced level proficiency in reading and writing and at least intermediate level proficiency in speaking. Additionally half credit courses may be offered for interested students on an elective basis – the emphasis here could be conversational and reading rather than on writing. 23 IV What kind of a person would a Jindal Liberal Arts Graduate Become? JSLH will be located within the ecology of a university setting with active schools of Law, Business, International Relations and Public Policy. A student of JSLH faces a diversity of possibilities, where each department becomes a distinct form of offering with courses in Contract Law, Intellectual Property, Human Rights and War Crimes, Conflict Resolution, Science Studies and Democratic Governance. Learning at JSLH is learning for diversity as we consider competence in diversity as the lynch pin of the global process. JSLH graduates will seek to be professionals in a complex world. Transnationalism is not only a corporate prerogative, it is a style developed to suit the emerging knowledge society. A Transnational Humanities course goes beyond the cross-disciplinary cosmopolitan exposure to explore new wholes and integrations of Knowledge. For a transnational humanities education, an understanding of both difference and integration is essential. One has to be rooted in a variety of cultures and access lives beyond one locality and one world view. Such a citizenship of the world adds a culture of competence, a web of skills which are critical in the new knowledge society, and crucial in the increasingly competitive job market. They will possess not only the means and techniques for self-expression and analysis for success in graduate school, but also the courage to go against the grain of received wisdom and achieve breakthroughs in scholarly discourse. A JSLH graduate is both a classicist and a paradigm breaker sensitive to the limits and possibilities of knowledge. JSLH conceptualizes education as a process of empowerment providing ethical frames, crosscultural understanding, linguistic skills and professional perspectives which create a sense of craftsmanship to examine the emerging issues of a global democracy. The setting for learning no longer remains the college campus; the process of learning begun at JSLH will continue unabated following its own rhythms across the world. A search for Liberal Arts is a global adventure. Welcome to O.P. Jindal Global University. 24 O.P. Jindal Global University Governing Body Chairman Mr. Naveen Jindal, Chancellor, O.P. Jindal Global University Members Professor C. Raj Kumar, Vice Chancellor, O.P. Jindal Global University Mr. Anand Goel, Joint Managing Director, Jindal Steel & Power Limited Dr. Sanjeev P. Sahni, Professor, Jindal Global Business School Dr. A. Francis Julian, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India Professor D.K. Srivastava, Former Pro Vice Chancellor (Academic), O. P. Jindal Global University Professor Jane E. Schukoske, CEO, Institute of Rural Research and Development (IRRAD) Professor Peter H. Schuck, Yale University Professor Stephen P. Marks, Harvard University Mr. S.S. Prasad, IAS, Secretary to Government of Haryana Education Department (Ex officio) Professor Y.S.R. Murthy, Registrar, O.P. Jindal Global University Board of Management Chairman Professor C. Raj Kumar, Vice Chancellor, O.P. Jindal Global University Members Mr. S.S. Prasad, IAS, Secretary to Government of Haryana Education Department (Ex officio) Dr. Sanjeev P. Sahni, Professor, Jindal Global Business School Dr. A. Francis Julian, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India Professor Y.S.R. Murthy, Registrar, O.P. Jindal Global University Professor Parmanand Singh, Former Dean, Faculty of Law, University of Delhi Dr. R.K. Raghavan, Consulting Advisor (Cyber Security), Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. Professor R. Sudarshan, Dean, Jindal School of Government and Public Policy Professor. C. Gopinath, Dean, Jindal Global Business School Professor Sreeram Sundar Chaulia, Dean, Jindal School of International Affairs Professor Padmanabha Ramanujam, Associate Professor & Associate Dean (Admissions and Outreach), Jindal Global Law School Dr. Shounak Roy Chowdhury, Assistant Professor and Assistant Dean (Admissions and Outreach), Jindal Global Business School Academic Council Chairman Professor C. Raj Kumar, Vice Chancellor, O.P. Jindal Global University Members Dr. Sanjeev P. Sahni, Professor, Jindal Global Business School Dr. A. Francis Julian, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India Professor N.R. Madhava Menon, Former Member, Centre State Relations Committee Mr. D.R. Kaarthikeyan, Former Director, Central Bureau of Investigation Professor Y.S.R. Murthy, Registrar, O.P. Jindal Global University Professor R. Sudarshan, Dean, Jindal School of Government and Public Policy Professor. C. Gopinath, Dean, Jindal Global Business School Professor Padmanabha Ramanujam, Associate Professor & Associate Dean (Admissions and Outreach), Jindal Global Law School Professor Dipika Jain, Associate Professor and Associate Dean (Academic Affairs), Jindal Global Law School Mr. Buddhi Prakash Chauhan, Director, Global Library, O.P. Jindal Global University Dr. Aseem Prakash, Associate Professor and Assistant Dean (Research and International Collaboration), Jindal School of Government and Public Policy Dr. Shounak Roy Chowdhury, Assistant Professor and Assistant Dean (Admissions and Outreach), Jindal Global Business School Professor Sreeram Sundar Chaulia, Dean, Jindal School of International Affairs Professor Mohsin Raza Khan, Assistant Professor and Assistant Dean (Student Initiative), Jindal School of International Affairs Mr. Manoj Vajpayee, Controller of Examinations O.P. Jindal Global University Sonipat Narela Road, Near Jagdishpur Village, Sonipat, Haryana-131001, NCR of Delhi, India Tel: +91-130-3057800 / 801 / 802; Fax: +91-130-3057888 Email: info@jgu.edu.in; Website: www.jgu.edu.in Tollfree: 1800 123 4343