THE ROMAN EMPIRE

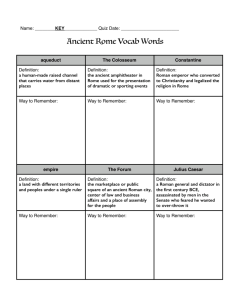

advertisement