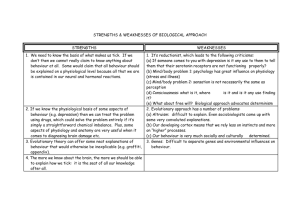

Transforming Behaviour Change

advertisement