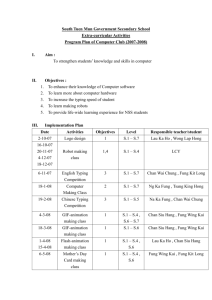

Document

advertisement