Global Business Strategy And Innovation

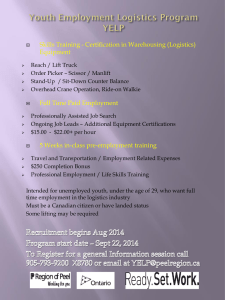

advertisement