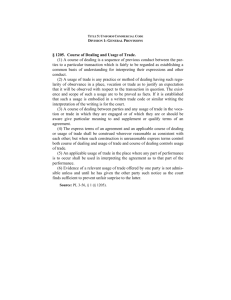

ELGAR TYING AND EXCLUSIVE DEALING CHAPTER

advertisement