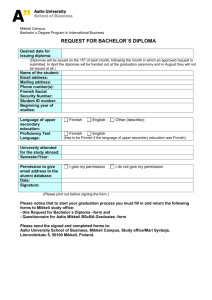

The school of opportunities

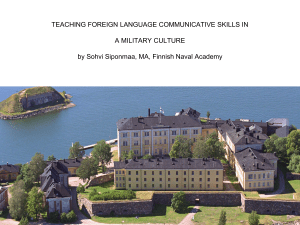

advertisement