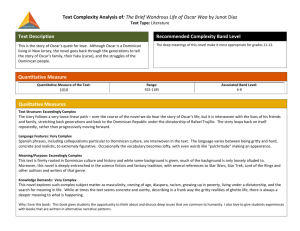

In the Sweet Balance of Dominican-‐‑American Identity: Diasporic

advertisement