Voyages of discovery

advertisement

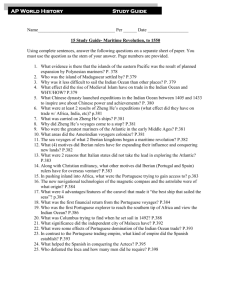

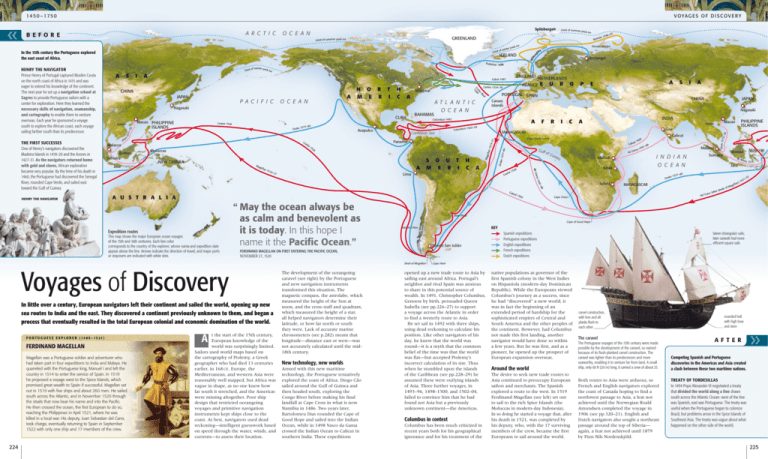

14 50 – 1750 v o ya g e s o f d i s c o v e r y Spitsbergen o c e a n St o c e a n t i h c Nagasaki Cuba islands Drake s re Pi Lo ais a Malacca Borneo Sumatra Moluccas New Guinea Ma ge l lan A T L AN T IC o c e a n Columbus 1492 Caribbean Sea A Columbu 15 26 a 151 9–2 1 h c a Magellan was a Portuguese soldier and adventurer who had taken part in four expeditions to India and Malaya. He quarreled with the Portuguese king, Manuel I and left the country in 1514 to enter the service of Spain. In 1519 he proposed a voyage west to the Spice Islands, which promised great wealth to Spain if successful. Magellan set out in 1519 with five ships and about 260 men. He sailed south across the Atlantic, and in November 1520 through the straits that now bear his name and into the Pacific. He then crossed the ocean, the first European to do so, reaching the Philippines in April 1521, where he was killed in a local war. His deputy, Juan Sebastian del Cano, took charge, eventually returning to Spain in September 1522 with only one ship and 17 members of the crew. New technology, new worlds Armed with this new maritime technology, the Portuguese tentatively explored the coast of Africa. Diogo Cão sailed around the Gulf of Guinea and then headed south, exploring the Congo River before making his final landfall at Cape Cross in what is now Namibia in 1486. Two years later, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed into the Indian Ocean, while in 1498 Vasco da Gama crossed the Indian Ocean to Calicut in southern India. These expeditions india a Philippine islands Macao Hainan 8 7–9 149 ma a G da Gu i ne a 150 0 Calicut 00 15 Malindi Kilwa Malacca i n d i a n o c e a n Dra Sofala Sumatra 80 577– ke 1 an del C Cape Cross de A b re Java Madagascar o Moluccas Borneo ) ll an a ge of M ath e d r (afte u 1511 2 –2 21 15 Cape of Good Hope Puerto San Julián November 27, 1520 t the start of the 15th century, European knowledge of the world was surprisingly limited. Sailors used world maps based on the cartography of Ptolemy, a Greek geographer who had died 13 centuries earlier, in 168 CE. Europe, the Mediterranean, and western Asia were reasonably well mapped, but Africa was vague in shape, as no one knew how far south it stretched, and the Americas were missing altogether. Poor ship design that restricted oceangoing voyages and primitive navigation instruments kept ships close to the coast. At best, navigators used dead reckoning—intelligent guesswork based on speed through the water, winds, and currents—to assess their location. c 98 7– 149 ma FERDINAND MAGELLAN A i KEY Isla de Chloe Ferdinand Magellan on first entering the Pacific Ocean, In little over a century, European navigators left their continent and sailed the world, opening up new sea routes to India and the east. They discovered a continent previously unknown to them, and began a process that eventually resulted in the total European colonial and economic domination of the world. JAPAN River Plate Strait of Magellan P ortuguese e x p l orer ( 1 4 8 0 – 1 5 2 1 ) 6 152 ral Voyages of Discovery a Goa Gulf of Loa a u s t r a l i a The development of the oceangoing caravel (see right) by the Portuguese and new navigation instruments transformed this situation. The magnetic compass, the astrolabe, which measured the height of the Sun at noon, and the cross-staff and quadrant, which measured the height of a star, all helped navigators determine their latitude, or how far north or south they were. Lack of accurate marine chronometers (see p.282) meant that longitude—distance east or west—was not accurately calculated until the mid18th century. r ral Cab Cab This map shows the major European ocean voyages of the 15th and 16th centuries. Each line color corresponds to the country of the explorer, whose name and expedition date appear above the line. Arrows indicate the direction of travel, and major ports or stopovers are indicated with white dots. f Cape Sierra Leone isa Lima “ May the ocean always be as calm and benevolent as it is today. In this hope I name it the Pacific Ocean.” i CHINA Madagascar Panama s o u t m e r i s Nagasaki 4 s 1502–0 Acapulco a E a da G Java 80 1577– P PORTUGAL SPAIN 151 9–2 1 Loaisa 1526 Bahamas EURO Canary Islands ellan 151 5–1 6 Macao Philippine FRANCE Cartier 1534–36 Montreal a Archangel england NETHERLANDS Cabot 1497 e 157 7–80 p a c i f i c a r r nce Novaya Zemlya 53 15 Drak JAPAN N o m e re aw .L l ea –R rte Co 500 1 CHINA Hainan ICELAND by gh –16 a ice pack nter of wi Frobisher 1576 Lab ra of winter pack Limit ice Expedition routes 224 sla nd Mag i Limit r HENRY THE NAVIGATOR s 97 – 596 nts 1 Bare do THE FIRST SUCCESSES One of Henry’s navigators discovered the Madeira Islands in 1418–20 and the Azores in 1427–31. As the navigators returned home with gold and slaves, African exploration became very popular. By the time of his death in 1460, the Portuguese had discovered the Senegal River, rounded Cape Verde, and sailed east toward the Gulf of Guinea. a ack ice Pires 1515 Baf fin I In the 15th century the Portuguese explored the east coast of Africa. HENRY THE NAVIGATOR Prince Henry of Portugal captured Muslim Ceuta on the north coast of Africa in 1415 and was eager to extend his knowledge of the continent. The next year he set up a navigation school at Sagres to provide Portuguese sailors with a center for exploration. Here they learned the necessary skills of navigation, seamanship, and cartography to enable them to venture overseas. Each year he sponsored a voyage south to explore the African coast, each voyage sailing farther south than its predecessor. Limit of summer p greenland Limit of summer pack ice Wi ll o u A R C T IC B E F O R E Spanish expeditions Portuguese expeditions English expeditions French expeditions Dutch expeditions lateen (triangular) sails; later caravels had more efficient square sails Cape Horn opened up a new trade route to Asia by sailing east around Africa. Portugal’s neighbor and rival Spain was anxious to share in this potential source of wealth. In 1491, Christopher Columbus, Genoese by birth, persuaded Queen Isabella (see pp.226–27) to support a voyage across the Atlantic in order to find a westerly route to Asia. He set sail in 1492 with three ships, using dead reckoning to calculate his position. Like other navigators of his day, he knew that the world was round—it is a myth that the common belief of the time was that the world was flat—but accepted Ptolemy’s incorrect calculation of its size. Thus when he stumbled upon the islands of the Caribbean (see pp.228–29) he assumed these were outlying islands of Asia. Three further voyages, in 1493–96, 1498–1500, and 1502–04, failed to convince him that he had found not Asia but a previously unknown continent—the Americas. Columbus in context Columbus has been much criticized in recent years both for his geographical ignorance and for his treatment of the native populations as governor of the first Spanish colony in the West Indies on Hispaniola (modern-day Dominican Republic). While the Europeans viewed Columbus’s journey as a success, since he had “discovered” a new world, it was in fact the beginning of an extended period of hardship for the sophisticated empires of Central and South America and the other peoples of the continent. However, had Columbus not made this first landing, another navigator would have done so within a few years. But he was first, and as a pioneer, he opened up the prospect of European expansion overseas. Around the world The desire to seek new trade routes to Asia continued to preoccupy European sailors and merchants. The Spanish explored a route to the west. In 1519 Ferdinand Magellan (see left) set out to sail to the rich Spice Islands (the Moluccas in modern-day Indonesia). In so doing he started a voyage that, after his death in 1521, was completed by his deputy, who, with the 17 surviving members of the crew, became the first Europeans to sail around the world. carvel construction, with fore and aft planks flush to each other The caravel The Portuguese voyages of the 15th century were made possible by the development of the caravel, so named because of its flush-planked carvel construction. The caravel was lighter than its predecessors and more seaworthy, enabling it to venture far from land. A small ship, only 60 ft (20 m) long, it carried a crew of about 25. Both routes to Asia were arduous, so French and English navigators explored the coast of Canada hoping to find a northwest passage to Asia, a feat not achieved until the Norwegian Roald Amundsen completed the voyage in 1906 (see pp.320–21). English and Dutch navigators also sought a northeast passage around the top of Siberia— again, a feat not achieved until 1879 by Finn Nils Nordenskjöld. rounded hull with high bow and stern A F T E R Competing Spanish and Portuguese discoveries in the Americas and Asia created a clash between these two maritime nations. TREATY OF TORDESILLAS In 1494 Pope Alexander VI negotiated a treaty that divided the world along a line drawn south across the Atlantic Ocean: west of the line was Spanish, east was Portuguese. The treaty was useful when the Portuguese began to colonize Brazil, but problems arose in the Spice Islands of Southeast Asia. The treaty was vague about what happened on the other side of the world. 225